The In-Between Moments: In Conversation with Nadia Younes

Throughout her multimedia practice, Nadia Younes offers glimpses into construction sites and liminal spaces to investigate themes of displacement and instability. Younes speaks with Lara Xenia about her family history, love for junkyards, and her material explorations.

Figure 1: Nadia Younes, Distilled Emptiness, 2024, oil on panel, 48 x 48 inches (121.92 x 121.92 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Nadia Younes

Lara Xenia: What’s a core memory of a place from your childhood?

Nadia Younes: One of my strongest memories is from the coast of Mauritania. My parents had a tough time there, and I was so young that I only remember bits and pieces. The clearest memory I have is of the dirt roads covered in seashells. I once picked one up, and a cascade of tiny shells spilled out. For a while, I actually thought that's how babies were born [laughter].

LX: That’s so sweet. I didn’t realize you spent time in Mauritania when you were little.

NY: Yes, I moved around a lot as a child. I was born in Nazareth, but when I was three, we moved to Mali, then to Mauritania and Jordan. Once we returned to Israel when I was five-and-a-half, I started learning Hebrew. Let me give you some family history…

Figure 2: Nadia Younes, Nature of Matter, 2022, oil on panel, 8 x 6 feet (243.84 x 182.88 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Nadia Younes

In 1947, my grandma was born in Ashkelon (historically known as al-Majdal/Asqalan) in what is now Israel. A year later, the 1948 Arab–Israeli War (al-Nakba/War of Independence) broke out, and her family was deported to Sinai, so she moved to Cairo. My dad was born there as the youngest of six children. Unfortunately, my grandfather died young, so my grandma had to move with her six children to Gaza, where she was at the mercy of her family. On the ground floor of the house she lived in, she ran a small convenience store selling cigarettes, juices, and snacks, on a route used mainly by the Israeli army from a nearby base and by settlers from Gush Katif.

I’ve been to the West Bank, Palestinian territories, and Jordan, but never to Gaza, because after I was born it was after the two intifadas, and the border was closed…you needed very special permits to get in or out.

Figure 3: Nadia Younes, Past Observation Process, 2022, 8 × 6 inches (20.32 × 15.24 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Nadia Younes

Figure 4: Nadia Younes, What’s Missing, 2023, oil and inkjet on paper, 35 x 34 inches (88.9 x 86.36 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Nadia Younes

LX: Oh wow, so your family was based in Gaza?

NY: Yes, my grandmother and her six children were still living there. In the mid-1980s, a U.S.-based real estate group approached her several times to buy the house and shop, saying the location was strategic for the military and nearby settlements. They even offered her Israeli citizenship. She initially rejected the offer, but then she acquiesced when the Gaza authorities pressured her to close the shop since many of her customers were Israelis. As a young widow raising six kids on her own in a tough environment, she eventually had no choice but to leave. When my dad was about sixteen, they packed up quietly one night and left and he ended up moving to Nazareth.

In the late 1990s, my mother, Tatiana, came to Israel as a tourist from Kronstadt, which is a small naval island near St. Petersburg. She had a hard time in Russia after the Soviet Union fell. My parents met at a nightclub in Nazareth. Her father struggled with alcoholism, and her mother, Liudmila, was very supportive, but they had lived through times of boiling their own shoes for broth.

LX: That’s really crazy. Would you say displacement and family traumas actively inform your creative process, or do you notice these influences more in retrospect?

Figure 5: Nadia Younes, Emptiness as a Verb No. 3, 2025, oil on panel, 12 x 9 inches (30.48 x 22.86 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Nadia Younes

NY: That's a great question. When I was younger, I turned to painting and crafts as a safe haven from my turbulent childhood, and mainly made self-portraits. I later shifted to depicting construction sites and industrial spaces, which I see as systems of neglect that raise questions about physical bodies, access, and restrictions. Moving from country to country without any stability made these spaces feel permanent to me because no matter where I went, there was always construction and broken architecture.

Over time, I realized that most of life unfolds in the in-between moments, rather than in cathartic ones. I’d notice an air duct on the street and see it as an entity in itself or a truism. I try to employ trompe l’oeil effects and realism to destabilize viewers’ assumptions by connecting to sites that feel like “no man’s land,” where the ground seems pulled from under me. I like the agency that materials possess, like when materials start looking back at you or the object becomes the subject.

LX: Your approach to architecture is fascinating. What informed Nostalgia for the Nonexistent and Nostalgia for the Missing?

Over time, I realized that most of life unfolds in the in-between moments, rather than in cathartic ones.

Figure 6: Nadia Younes, Nostalgia for the Nonexistent, 2024, oil on panel, 36 x 24 inches (91.44 x 69.96 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Nadia Younes

Figure 7: Nadia Younes, Nostalgia for the Missing, 2024, oil on panel, 36 x 24 inches (91.44 x 60.94 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Nadia Younes

NY: As someone who lived in Israel for a while, I immediately recognized the architectural codes of the region when Sergey Kadochnikov, my best friend and collaborator from Jerusalem, shared the image with me. It was quite poetic to paint a site I never physically occupied, and to test how memory, fantasy, and distance could produce its own language. I honestly felt compelled to paint his photographs after moving away from our shared life and creative partnership.

LX: That’s so fruitful to have a friendship like that. So your air ducts embody bodies?

Figure 8: Nadia Younes, Nowhere, 2024, oil on panel, 8 x 6 inches (15.24 x 20.32 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Nadia Younes

NY: Yes, or something that’s unfamiliar. When I deal with construction sites and industrial areas, usually I see them as a universal code for temporality, access, social hierarchies, and gender roles, since construction sites are usually dominated by men or by me and my studio apprentice.

I love going to the metal junkyard in New Haven [smiles]. Sometimes I honestly prefer to go there rather than the museum to get more inspiration. I just feel alive there [laughter]! I’m intrigued by the transactional dynamics of how as two women my apprentice and I have to adjust to being allowed in those spaces to get what we need from the junkyard.

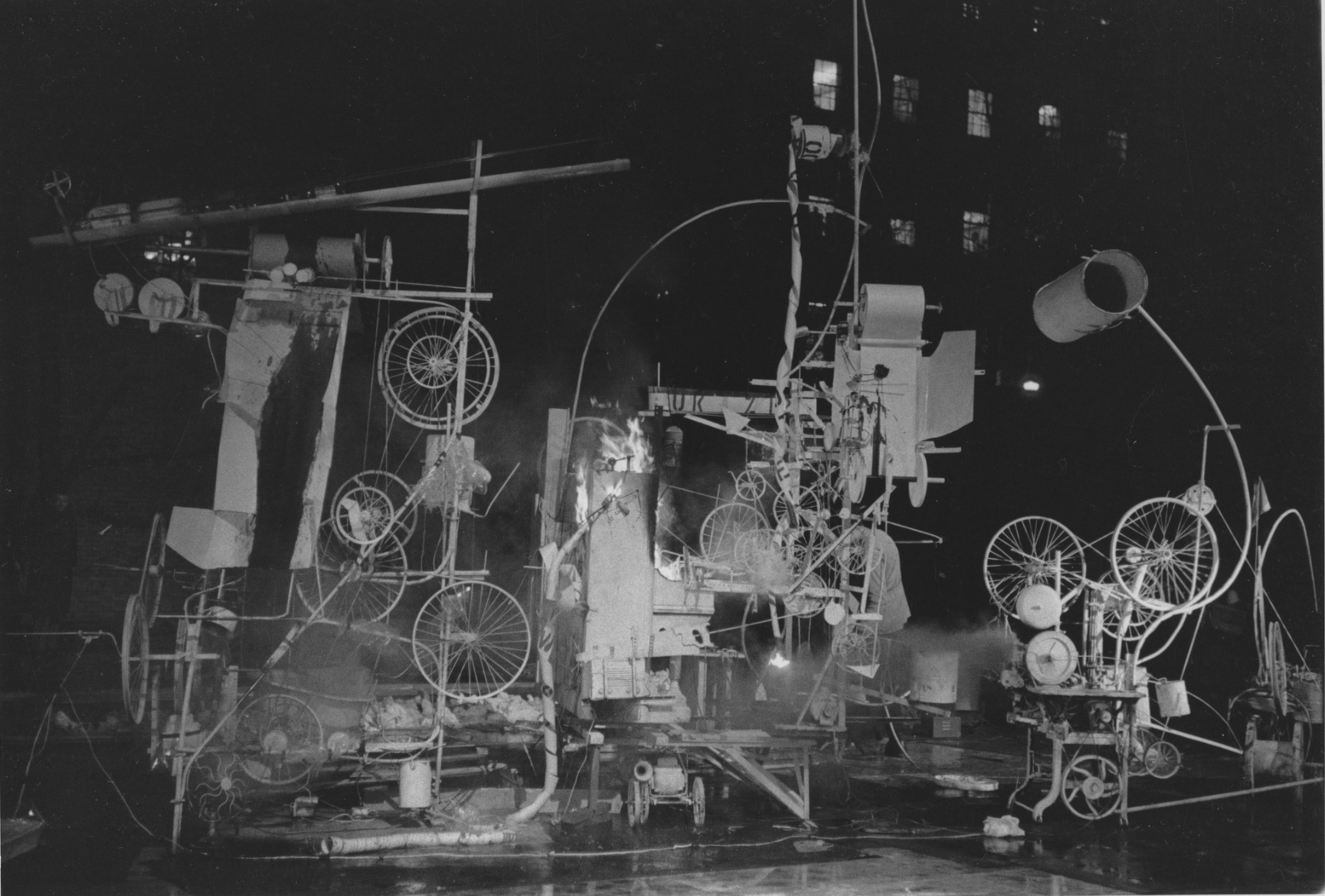

Figure 9: Jean Tinguely, Installation view of the exhibition Homage to New York: A self-constructing and self-destroying work of art conceived and built by Jean Tinguely, March 17, 1960. Photographic archive. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York, New York (IN661.1). Video footage: courtesy © Museum Tinguely, Basel, Switzerland, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6dgGu2w3Qvo

LX: I like that you like literal detritus. That kind of reminds me of how Jean Tinguely salvaged bicycles and scraps from Newark’s junkyard to create Homage to New York. He showcased his “suicidal sculpture” in MoMA’s garden in March 1960 and the fire department had to put it out after it burst into flames.

NY: I could totally see myself doing that [laughter].

LX: What’s the story behind the work with scrawled writing on the walls?

Figure 10: Nadia Younes, Ouroboros (Novembers), 2024, oil, charcoal and paper on panel, 72 x 48 inches (182.88 x 121.92 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Nadia Younes

NY: I made this painting in November 2023 when I was grieving my dog’s passing, my mom’s relapse into alcoholism, and the outbreak of war, so I chose to expose the panel and mark it with charcoal and pencil as I wrestled with my thoughts. I was dealing with an eating disorder and a sudden loss of control. Even small differences, like food labels switching from grams to “per serving” felt disorienting.

I’d often stare out the window at a nail in the frame and the empty blue sky beyond to ground myself, and in that same corner, I had taped a church pamphlet I once picked up that said, “Why must I suffer?” I wrote it largescale across the gallery wall in large charcoal next to complement this work. I often return to the image of the ouroboros, the snake that eats its own tail, bringing itself to life and killing itself in a never-ending cycle.

LX: Oh, I’m sorry you went through that. It's interesting that you chose ouroboros as a reference too. Were those dark times prompted more by your external environment that shaped it?

NY: It was absolutely circumstantial because in my heart, I believe that there is a lot of love in the world, and a lot of beautiful reciprocity. We can choose to surround ourselves with kindness and compassion daily. Looking at it now, a lot of my work deals with pain…I don't think that I paint happy subjects…[laughs]

LX: Do your thesis sculptures grapple with that? Take me through your process.

Figure 11: Nadia Younes, Another Fine Portal Mess, 2025, mixed media, 45 x 45 inches (114.3 x 114.3 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Nadia Younes

Figure 12: Nadia Younes, Another Fine Portal Mess (detail), 2025, mixed media, 45 x 45 inches (114.3 x 114.3 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Nadia Younes

NY: I see those two works in tandem with one another. For those works, I wondered what it meant to carry something with you when you’re uprooted, so that inspired both works.

Another Fine Portal Mess was a failed attempt to cast Compression Field. For Another Fine Portal Mess, I first used a trash bag coated with tar as a mold and tried using five gallons (so 102.5 pounds) of resin to make it. When I used a heat gun to get a globby effect, it grew too heavy, sank, and leaked, revealing the black layer underneath. The fumes were so strong the safety office cleared out my studio and banned me for three days because it was super toxic. I’m not proud of it, but it shows how volatile my process can be. Back in Israel, I worked with melting lead and plastic tarps. They respond to touch and pressure in a way metals like aluminium or steel can’t because it has a low temperature, and when it melts, it's shiny.

LX: Lead? Like Caravaggio lead? Nadia, that’s insane! [Laughter] Also, how heavy is this thing?

NY: About 50–60 pounds. Two people need to lift it. Yale’s department nearly barred me from showing it in the thesis show because of toxicity concerns, but by the thesis show Another Portal Mess had already stopped off-gassing, and Compression Field was produced safely, even as it kept resisting and leaking onto the floor of the gallery. For me, though, the instability and volatility of these works is essential. I’m drawn to objects that behave as if they have a life and desire of their own.

Compression Field a successful attempt. I wanted the bag to conjure a body, a womb, or a vessel that couldn’t hold its contents within. I cast it using resin in a large industrial chemical bin using sand and water. The water acted as a placeholder for the resin, and displaced it into a kiddie pool as I poured. I lined a trash can with a trash bag as a makeshift mold and worked around sand reserved for pewter. When I pulled it from the mold, it seemed to have shaped itself [laughs].

I wanted the bag to conjure a body, a womb, or a vessel that couldn’t hold its contents within.

Resin doesn’t react well to moisture, so the environment was hostile from the start. I think constantly about temperature and conditions, and about how to make metal and other stubborn materials feel warm, responsive, and almost living materials. The result felt less like control and more like a negotiation with the material. I then filled the interior with flexible metal conduits salvaged outside the Jewish Life Center’s construction site at Yale. It still had fragments of the wall and its residue felt poetic, like a system trying and failing to contain its past or history.

LX: That’s really cool. The way you connect belonging, volatility, and transience to self-understanding is moving. What was that vision?

NY: Compression Field emerged from a visceral childhood memory of carrying glass bottles of Heineken for my mother in a black bodega bag while my dad was at work. When I tried to ration her beer, she lost control, so I called the police, expecting protection, but they only questioned who sold the alcohol to a child. In the end, the blame fell on me.

Figure 13: Nadia Younes, Compression Field, 2025, resin, FMC, wall chunks, rusty chain, 30 x 20 x 20 inches (76.2 x 50.8 x 50.8 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Nadia Younes. For additional documentation please visit: https://nadia-younes.com/work/mfa-thesis-yale-school-of-art

That moment revealed how fragile support systems can be and characterized functional and dysfunctional systems. As a kid you believe you have choice, but that illusion leaves you carrying a responsibility for things beyond your control. So both works are a response to that rupture.

LX: It seems like you like that dichotomy.

NY: I really do seek it. I enjoy being in that tension.

LX: Which artists have inspired you?

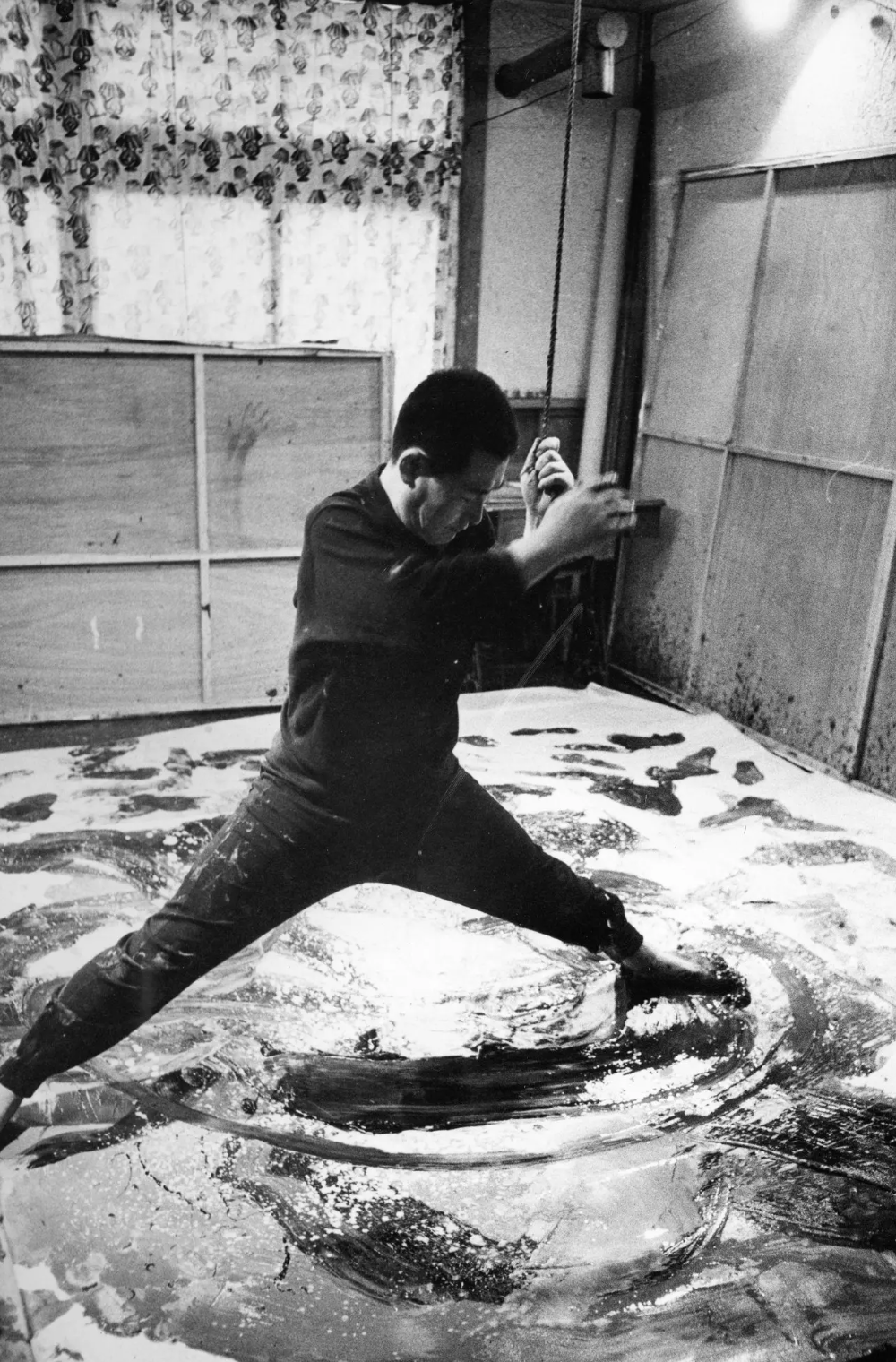

Figure 14: Kazuo Shiraga in his studio, 1960. Photo: courtesy Amagasaki Cultural Center and The New York Times. Image source: https://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/02/arts/international/art-world-rediscovers-kazuo-shiraga.html

NY: I think a lot about Kazuo Shiraga, the Japanese Gutai artist. I first saw his work at MoMA in 2021, soon after coming to New York. I love the tension between the delicacy of the papers and the weight of the paint and the raw evidence of the body in his work. I also think about Sylvia Plath in relation to that a lot and really resonated with The Bell Jar for its portrayal of depression and the way she framed an autobiographical story as a novel.

LX: Oh, I love the Gutai group and that’s on my book list. Is there anything you want to be known by?

That moment revealed how fragile support systems can be and characterized functional and dysfunctional systems.

NY: As an artist of my time, yes. I want to open the possibility that a lot of truths can exist simultaneously, and that in terms of our existence, we exist and therefore we suffer. I think about it as universal. I want to relate to the viewers and to people on an emotional level.

LX: What’s something that you live by?

Figure 15: Nadia Younes, Phantom Fragments, 2022, oil and charcoal on panel, 8 x 11 feet (243.84 x 335.28 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Nadia Younes

NY: J. Cole is one of my favorite artists, and he has a line I love: “Sometimes you gotta step away, do some living, let time provide a new prescription.” I feel that deeply because I feel like everything in life has a price.

Nadia Younes

Nadia Younes is an interdisciplinary artist working across painting, sculpture, installation, video, and writing. Born in Nazareth to a Palestinian refugee father and a Soviet immigrant mother, she moved between Israel, Mali, Mauritania, Jordan, and Russia. This transitory upbringing shaped her sensitivity to displacement, instability, and overlooked spatial systems, concerns that are central to her practice.

Her work explores tensions between surface and structure, access and refusal, containment and collapse. Drawing from industrial materials and urban demolition sites, she merges classical painting methods with cast resin, paint skins, flexible metal conduit, and other construction remnants. She treats these materials as bearing the memory of bodies in flux, reflecting systems of labor, gender, and survival. Multilingual in English, Arabic, Hebrew, and Russian, Younes approaches materials as she does language: as codes that can be bent, fractured, and reassembled.

Recent presentations include PowerLine at Perrotin, New York (2025), a public video screening with ZAZ10TS in Times Square (2024), and the solo exhibition Elusive Territories at The Study at Yale (2024). Select works include Interference Pattern, a mirrored environment featuring a suspended car and circulating liquids; Site of Failure, a kinetic installation composed of acrylic paint skins; Compression Field, a 450-pound resin sculpture embedded with demolition debris; and Second Lesson in Boundaries, a trompe-l’œil oil painting that reflects surveillance and fencing systems in Israel and the West Bank.

She holds an MFA in Painting and Printmaking from the Yale School of Art and a BFA from the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem. Her training includes scientific glassblowing, lithography, marble carving, and classical studies at the Imperial Academy in St. Petersburg. Younes has served as a graduate assistant at the Yale School of Art, taught at Bezalel, and engaged in community-based initiatives. She received support from residencies such as the Vermont Studio Center and ISPMFA, and was the recipient of the Winsor & Newton Award for Excellence in Painting. She is currently based between New Haven and New York.