Nightvision: In Conversation with Z.T. Nguyễn

Z.T. Nguyễn speaks with Lara Xenia about how insects, queer theory, and revolutions inform his rigorous drawing practice.

Figure 1: Z.T. Nguyễn, A sort of delicious terror (detail), graphite, colored pencil, and acrylic on letter-sized sheets of paper, 83 x 73 inches (unframed) (210 x 185.42 cm [unframed]). Photo: courtesy the artist, Perrotin Gallery, and Guillaume Ziccarelli © Z.T. Nguyễn and Perrotin

Lara Xenia: What is “home” for you?

Z.T. Nguyễn: I'm actually in a temporary living situation right now, with my parents. I do feel comfortable here since I'm around my family members, but knowing it won't last makes me feel more like a visitor, like I'm untethered and floating…not just in terms of where I'm living, but also my community, my belongings, not having a studio while I'm here. So maybe “home" for me is something that’s steady under my feet. It doesn't necessarily need to be a place, but something that’s reliable and rooted.

LX: I'm really interested in how you configure forms in space and cropped bodies within your compositions. What got you interested in figurative works?

ZTN: Representing the body—mostly my own body—has always been a pretty natural inclination for me in my work. I'm very aware of my body language and physical sensations in public spaces because they’re indicative of my social surroundings. How am I being perceived and how am I perceiving other people right now? The answers manifest in my stomach, on my skin, in the way I speak and make eye contact. I think this bodily social awareness is heightened by the fact that I'm queer and not white. That's definitely something I instinctively pay a lot of attention to, having grown up in a rural community that had very few other people like me.

Figure 2: Z.T. Nguyễn, Waiting, graphite and acrylic on letter-sized sheets of paper, 42.25 x 32.25 inches (107.32 x 81.92 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Z.T. Nguyễn

So the cropped or fractured body is sort of my way of zeroing in on the physical sensations that emerge from otherness. I think there's something about incompleteness that I'm interested in, too. Like, the incompleteness of identity, of history, or even the incompleteness of my grasp on the Vietnamese language, which is what I speak with my family in a really fragmented manner.

LX: I love that. Are you first gen American as well?

ZTN: I’m part of the first generation in my family to be born here, yes. But my parents came here when they were kids, so they’re quite American…I don't have a lot of the same burdens that other young Asian Americans have, like needing to translate conversations and documents for my relatives. Still though, my family's histories as refugees and their experiences with displacement and marginalization in places like Oklahoma, Florida, and Maryland are deeply important to me.

LX: I see. And what about insects? How did your moth drawings first come about?

ZTN: The moth motifs are part of a more general interest I've had for a while in nocturnality and the nighttime, but they’re actually a way for me to think about my family, too. Most of the moths I draw are based on a group known as “Asian American moon moths,” which includes the Luna Moth and is part of a larger moth family called Saturniids. I was originally drawn to them because of their classification as “Asian American,” which is used by entomologists to describe their geographic range from Afghanistan and the Indian Subcontinent eastward, all the way to the Americas. But a key feature of these moths—the thing that led me to draw them so much in my work—is that they lose functionality of their digestive systems after they pupate. Rather than eating and nourishing themselves, their sole purpose in their final, most beautiful stage of life is to mate and provide for the next generation. And after just a few days as fully-formed moths, they die.

Figure 3: Z.T. Nguyễn, Moth, graphite and wall paint on letter-sized sheets of paper, 16.25 x 8 inches (41.28 x 20.32 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Z.T. Nguyễn

LX: In what part did that feel like your family?

ZTN: The sacrifice in having no other option but to provide for the next generation. Luckily my family members are indeed able to eat, and have fully-functioning digestive systems, for now [laughs]. But I think that the biology of these moths feels analogous to my parents’ and grandparents’ values and how I interpret their struggles in the US. Moths are primarily active in the night, which is a larger theme in my practice, as I mentioned. The night, for me, has a lot to do with waiting and transformation and the potential energy that builds before change occurs. In my piece Moth, which I did in the fall of 2023, I cut a drawing of the night sky into the silhouette of a moth. There's something about the briefness of an Asian American moon moth’s lifespan versus the ancientness of stars that appeals to me. What does it mean to compress these giant, almost incomprehensible cosmic objects in the night sky—most of which are larger and sometimes older than our own solar system's sun—down into the shape of something as simple and short-lived as a moth? I think it speaks to the infinitude I see in my family members and even in myself.

LX: And what about the mosquitoes that often show up in your work? Are those related to your family, too?

The night, for me, has a lot to do with waiting and transformation and the potential energy that builds before change occurs.

ZTN: To a degree, yes. Mosquitoes are also nocturnal like moths, which is a big reason why I tend to draw them. But unlike moths, especially large and beautiful Asian American moon moths like the Luna Moth, mosquitoes are basically universally despised [laughs]. The first drawing I made at Yale in 2023 was called Dandelion, and it had these mosquitoes in it that were menacingly large and chunky, flying around two pairs of feet and a dandelion that had lost all its seeds and petals. I was thinking about the floor and how it's often overlooked or considered dirty, but how it's also the plane that supports our bodies. I was also thinking a lot about weeds and overgrowth. Even though there's a lot of beauty to be found in that space, the mosquitoes were there as a sort of threat. I’m really interested in the precarity of mosquitoes, and how they might disrupt the otherwise tranquil register of an image. That precarity certainly resonates with me when I think about my family's history, and mosquitoes themselves also have a direct reference to heat and the tropics.

Figure 4: Z.T. Nguyễn, Dandelion, graphite and wall paint on letter-sized sheets of paper, 68.75 x 26 inches (174.63 x 66.04 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Z.T. Nguyễn

My mom is from Laos and my dad is from Vietnam, so I also think a lot about the tropics as an alternate modality. The ways that heat, humidity, infertile soil, and challenging topographies force people to abandon ways of living that are standard in temperate regions, which often include countries in the Global North. That environmentally-forced turn away from colonial norms is really inspiring to me. Like land itself rejects colonization. There's a lot we can learn from it. That being said, I've never lived in either Laos or Vietnam myself, but motifs like mosquitoes, which are often associated with heat and the tropics, are reminders that I'm still deeply invested in where my family is from.

LX: I can see how they evoke heat.

ZTN: Yeah. Here in North America, mosquitoes are only really out on summer nights, which kinda feels really queer to me. Or more specifically, gay [laughs]. I was taking this class called Queer Strategies at Yale, which is typically offered every fall in the School of Art; a few of us called it “gay class” as a joke [laughs]. And I talked about mosquitoes a lot during that class, actually. Beyond the “summer nights" thing, mosquitoes are also associated with disease, they suck on bodily fluids, they're mostly invisible until you spot them up close, they're widely regarded as pests, and many people actually want them vanquished from the face of the planet despite them being vital to ecosystems in basically every biome they occupy. Sounds pretty gay to me [laughs]! But in all seriousness, I don't want to use them as an anthropomorphic symbol or anything because mosquitoes are also responsible for more human deaths than any other animal… Again, I'd say it's more about the precarity that they evoke. There was a lot of queer theory we read in Queer Strategies that complemented this pretty well, too.

That precarity [of mosquitos] certainly resonates with me when I think about my family's history, and mosquitoes themselves also have a direct reference to heat and the tropics.

LX: I love queer theory. Did you read any Whitney Chadwick or Richard Meyer?

ZTN: Not for the class, but on my own, yeah! From the Queer Strategies reading list there was Ursula K. Le Guin's Author of the Acacia Seeds, Gregg Bordowitz's Questions, and Eva Hayward's Spiderwomen, which were all particularly impactful on me. Outside of that class, though, another faculty member brought to my attention this poem by John Donne called The Flea. In the poem, two lovers can only meet through a flea that bites both of them, so their blood could mingle inside of its body. She thought it was relevant to my mosquito drawings, especially Dandelion, and I agreed. I was really struck by it and have continued to think about it a lot—that gross but also sweet and tragic sentiment. It was really interesting to me. It felt in sync with the weird affective mode that I was wanting to work with, and it still resonates with me now.

LXM: Could you tell me about Mosquito Star?

Figure 5: Z.T. Nguyễn, Mosquito Star, graphite and wall paint on letter-sized sheets of paper, 32 x 31.5 inches (81.8 x 80.01 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Z.T. Nguyễn

ZTN: Sure! I've already talked about mosquitoes, so I guess I can talk about the star as a separate motif. There are two types of stars I frequently return to in my work: the naturalistic star, which I used in Moth, and then the five-pointed star, which is a representation of the naturalistic star, but an oversimplification of it. It's like cutting down a real star—like, an ancient, celestial entity—into a simple, easily reproduced shape that's mostly found in human political contexts. I'm really interested in that oversimplification as it pertains to politics.

Mosquitoes fly around pretty randomly, without any sense of order or synchronization; so, for them to form up into a five-pointed star like the one in Mosquito Star would be, like, really unusual and unlikely. So, I’d say this work is really about the unnerving and precarious nature of human politics. This kind of star is also a big part of the Vietnamese flag, so I’ve also thought a lot about this work in relation to the circumstances of modern Vietnam's formation, which was an immensely violent part of history, largely because of French and Japanese colonialism but also more famously because of US intervention and escalation. So I think Mosquito Star, and my use of five-pointed stars in general, could be understood as a sort of a critique of the extreme measures that powerful countries took in order to assert control and influence in Vietnam during that time of revolution. This year, 2025, marks the 50th anniversary of the end of the US Wars in Southeast Asia, including the Vietnam War, which is still a point of extreme sensitivity for a lot of people.

LX: It’s really brave that you’re even approaching this in your art. Artists are always exploring themselves, sometimes subconsciously, through what they absorb day to day. As a child of immigrants, I think grappling with that history is especially powerful because you’re trying to tap into your family’s narrative.

ZTN: Thank you. Yeah, and the five-pointed star is not unique to Vietnam, either. These stars are on a lot of flags: the US, Morocco, Pakistan, China, Honduras, Somalia, Myanmar, Cuba. The list goes on and on and on. And so that oversimplification that the shape does to naturalistic stars—that emphasis on the unnatural, sharp-edged mechanics of human politics—it's a reminder that it's really something that’s happened globally, not just in Vietnamese political history. And what’s more is that history is still ongoing today, too. Like, in the US, Southeast Asian refugees are still being specifically targeted and deported by the masses, which has been quietly going on for almost two decades now, and no one seems to be aware of how deeply it’s been disrupting our communities. And it's only, like, one of many loose strings from the wars that were left untied. It just makes me think about how many political injustices are still very much ongoing and still unfolding today all over the world, whether or not they're considered “over,” you know?

LX: Do you think of that temporality at all within your work?

ZTN: Definitely. I'd even say temporality in general is another kind of subject matter or motif for me, just like bodies or insects or the night, since a lot of the paper surfaces I draw on are folded and can be carried in a pocket or a bag. I like the idea of a drawing being carried by me—or by anyone, really—over the course of time, across various locations and periods of someone's life. Sometimes I have my friends hold onto drawings or pieces of paper that I haven't drawn onto yet. But when I carry them with me, I take them out, unfold them, look at them for a while, I hang them on the wall, and then I refold them back up before moving them somewhere else. They're like keepsakes or talismans, kind of. Or maybe curses, depending on the drawing [laughs]. But every time they get folded, that history—that time that I spent with them—it gets permanently recorded on their surfaces.

LX: Do you want the eventual owner of the work to be able to carry it in their pocket, the way someone might keep a photo of a loved one in a wallet? Is that a way of keeping it “close to home”?

ZTN: If they buy it unframed, I usually tell collectors that they can do as they wish with the drawings. The folding and carrying is part of the creation of the work, which has the potential to continue for as long as I have possession of it. But once someone buys an unframed work, they can choose to continue that process or keep it as it is. But I like that idea of folding and portability as having some kind of relation to “home.” Come to think of it, maybe I should add that to my answer to your first question [laughs]! So, “home” for me is also what we carry with us across time and geographies, the things that continuously witness our changes and transformations. I guess the idea of “home" being decidedly separate from a geographic location makes real sense, too, in the context of my practice and family history. The folded sheet of paper, for me, evokes documents—especially refugee documents like the asylum forms or identification papers that my parents and grandparents might’ve carried with them. I'm interested in the fold as indicative of something that’s necessary to hold onto for safekeeping, yet at the same time it's not precious or holy enough to preserve in perfect condition. That’s where the folds in my drawings come from, really: thinking about putting away an important document and taking it back out as needed, over and over and over and over. Most of the drawings are even built from document-sized sheets, like I'm working with the materiality of the immigration system itself.

The folded sheet of paper, for me, evokes documents—especially refugee documents like the asylum forms or identification papers that my parents and grandparents might’ve carried with them […] That’s where the folds in my drawings come from, really: thinking about putting away an important document and taking it back out as needed, over and over and over and over.

LX: The fact that one paper could be indicative of if someone’s a citizen of a place or not is still conceptually insane to me, even on a humanity front.

ZTN: Yeah, like somebody's humanity and value being reduced down to nothing more than an 8.5 x 11. It really is a violent thing to classify people into categories and bits of data that determine their livelihood, their health, safety, and where they can live. At the same time, though, the sheet of paper is also used for a plethora of other purposes that might not be associated with violence at all! Like, love letters and recipes and books. So the real culprit here, I think, is standardization and the things that come with it: regulation, bureaucracy, and control.

LX: Tell me about Starlit.

Figure 6: Z.T. Nguyễn, Starlit, graphite and acrylic on letter-sized sheets of paper, 40.5 x 32 inches (102.87 x 81.28 cm). Photo: courtesy the art and Pat Garcia © Z.T. Nguyễn and Pat Garcia

ZTN: So this piece is probably the start of the transition from my earlier work at Yale—which makes up most of what we've already talked about so far—to where my ideas are at now. It consists of a few motifs we've already discussed: folded paper, a five-pointed star, and an Asian American moon moth—specifically, a Pink Spirit Moth, which is indigenous to Laos and Vietnam. What's newer here is the pocket knife, which is based on the one my father carries, the severed head, and heavily saturated color. The head might be related to the cropped bodies we talked about towards the beginning, but I think it's really its own thing. When I draw heads without bodies, they aren't necessarily dead or decapitated, since I imagine them still capable of seeing, hearing, thinking, and speaking, but incapable of moving. That tension, that powerlessness or helplessness, definitely has political origins for me.

I made Starlit during the summer of 2024, following a peak in widespread student-led political movements on campus during my time at Yale, which was met with police violence and aggressive retaliation from the university's administration. The same was happening on university campuses across the US and throughout the world. I participated in these movements firsthand, helped to organize them, witnessed the university's response in real time, all while seeing multiple genocides that were happening—that are still happening—on social media and press coverage… and it all really profoundly impacted me. These administrative and militarized systems, whether people are working within or directly against them, are just so much bigger than any of us individually. That sense of scale and of being small in the face of something vast—that's what the severed head is to me. It's a political motif. The knife, too, with its sharpness and inherent danger as a weapon, is kind of like the mosquito and tied to precarity. But what I don't want for this work is for it to defend inaction. I think, if anything, making this work encouraged me to think more on ways to take action, to seek out collective power because of my powerlessness as an individual. I think of this piece as a snapshot of a particular emotional and political moment that deeply affected me.

The works that I made after Starlit—from that summer until now—share these political influences and lean more into the nocturnal or nighttime theme I mentioned earlier in our conversation. A number of these works ended up becoming my thesis at Yale, and most were included in my first solo show, Facts Are Bigger in the Dark, which was shown at island this past summer, which is a gallery in New York's Chinatown.

Figure 7: Z.T. Nguyễn, Cat and Mosquitoes, graphite and acrylic on letter-sized sheets of paper, 40.5 x 32 inches (102.87 x 81.28 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist and Pat Garcia © Z.T. Nguyễn and Pat Garcia

LX: How did the show's nocturnal theme relate to politics?

ZTN: I think it's metaphorical or allegorical for revolutionary potential, but I'm not always interested in depicting that explicitly in my work; I'm more interested in harnessing what that potential feels like, and what inspires it. I started describing the night as a way of exploring the psychological space between stasis and change. Even if the works don’t look like night, they all live there in that transitional space. The darkness of night makes it hard to see clearly, and that demands different ways of moving through the world. That's why a lot of the animals that appear in my work are nocturnal—from moths and mosquitoes to cats. I almost always choose animals based on what helps them to navigate the night and survive. Moths have powdered wing textures that can make their flight silent and disrupt a bat's echolocation. For cats, it's their nocturnal vision and stalking. But since human figures were the real anchor of the show, sometimes they even took on these qualities to make it through the night, like a person who could turn their head all the way around like an owl. I'm really interested in human activities that happen regularly, or even exclusively, under the cover of the night’s darkness: parties, sex, drugs, crime, but also dissent, resistance, escape, and even witchcraft or communication with demons and spirits. I think witches are revolutionary beings. I haven't referenced witchcraft directly in my work, since I'm unfortunately not a witch myself, but I find them fascinating. On the other hand, I do have experiences with ghosts, and so does my family.

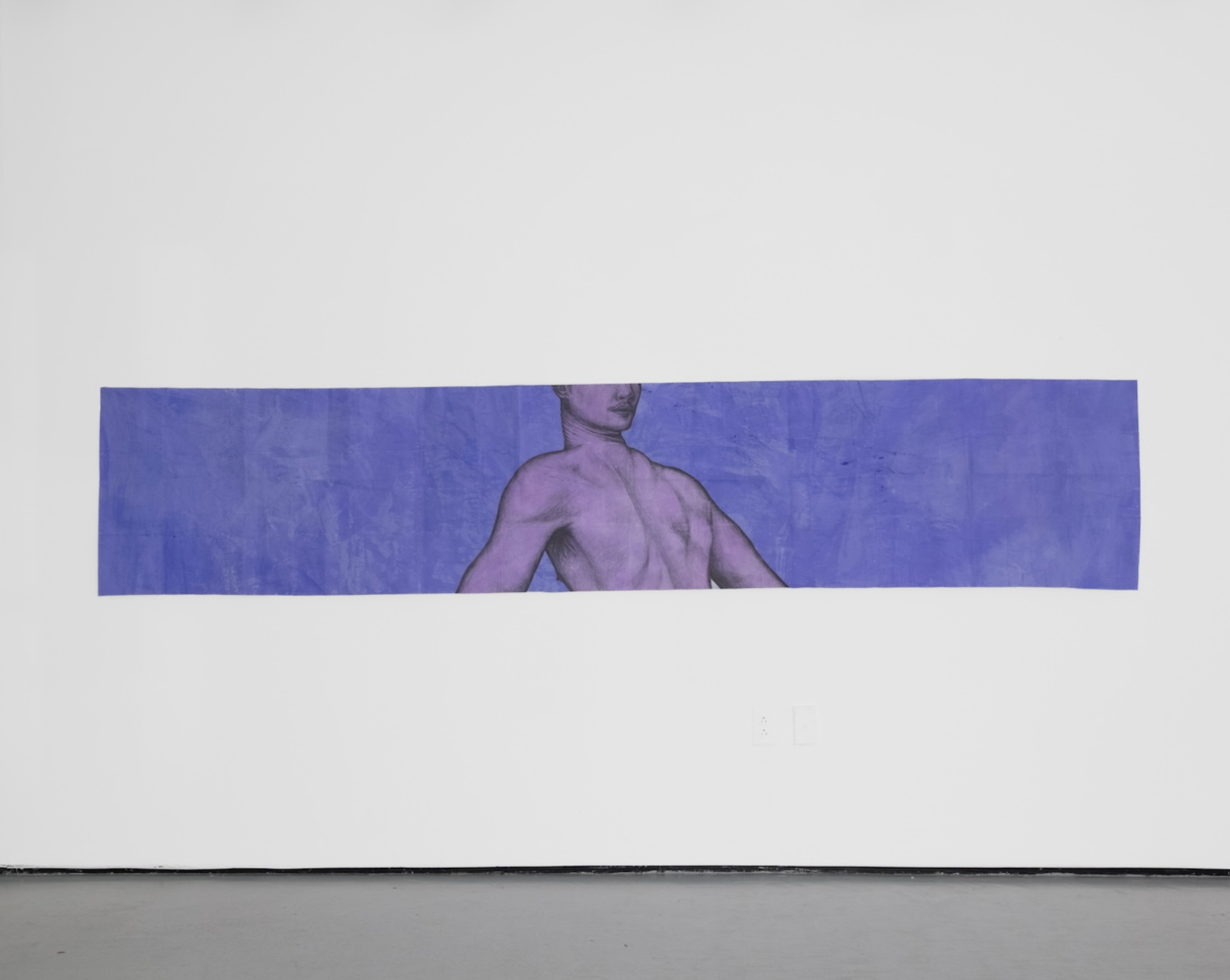

Figure 8: Z.T. Nguyễn, Neck, graphite and acrylic on letter-sized sheets of paper, 26 x 130 inches (66.04 x 330.2 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist and Pat Garcia © Z.T. Nguyễn and Pat Garcia

LX: Is your family superstitious?

ZTN: A bit, yes. We definitely believe in ghosts, at the very least. My parents and I were just talking about this last night, actually, and sharing ghost stories, bringing up people we know who are true mediums. I personally am not a medium by any means, but when I lived in Providence as an undergrad at RISD, I definitely had my fair share of ghost encounters. We also talked a bit about bùa ngải, which is a type of evil sorcery in Vietnam that involves curses, blood rituals, and mind control.

I'm really interested in human activities that happen regularly, or even exclusively, under the cover of the night’s darkness: parties, sex, drugs, crime, but also dissent, resistance, escape, and even witchcraft or communication with demons and spirits.

LX: Why did you choose to anchor the body and why did you choose these particular hues for your show?

ZTN: I think the body felt pretty natural of a choice for me. I talked about it a bit towards the beginning of our conversation, but most of the bodies I draw are my own. They're depictions of my physical sensations that come from experiences of otherness, which have largely informed my political engagements and interests. My colors, on the other hand, were chosen based on their proximity to or their distance from the color red. I was reading Anne Carson's Autobiography of Red and Eros the Bittersweet while making a lot of this work. The latter uses examples of Sappho’s poetry to explain that desire requires a space, a distance, between the desirer and the desired in order to exist. That space is comparable to the nighttime for me, because it’s a liminal zone between stasis and change. I started associating that space with red, thanks to Autobiography of Red, but also because of forces like lust, anger, or ecstasy which feel both like the color red and frustratingly liminal to me. When I chose colors for the drawings that eventually were included in the show, it was always about their relationship to red, to that emotional space. Purple and indigo felt like a few steps away from it; orange was closer, but standing on edge nearby; and pink was a muted, softer version of it, nestled beside it. Every color choice could be traced back to red as the emotional origin.

Figure 9: Z.T. Nguyễn, Insectoid, graphite and acrylic on letter-sized sheets of paper, 32 x 32 inches (81.28 x 81.28 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Z.T. Nguyễn and Pat Garcia

LX: What is the CRT in Watching about?

Figure 10: Z.T. Nguyễn, Watching, hand-drawn digital image, found CRT television, acrylic-pigmented cement, dimensions variable. Photo: courtesy the artist and island © Z.T. Nguyễn and island

ZTN: I grew up with CRT TV sets, so I think it evokes a sense of domesticity, like it's a snapshot of the home at night. But it isn't necessarily a warm or welcoming home space, which I think is felt though the cement pill bottles and beer bottles and that garish magenta color, but also in the other furniture piece in the show, which is a chair that's flipped over with a drawing hanging on its underside. I’d been wanting to use the backsides and undersides of discarded furniture pieces as unconventional frames for my drawings, since they're the parts of the furniture that you're not supposed to see, which affects the conceptual context for viewing the drawings. Like, is this drawing a secret that I'm only seeing because someone happened to flip this chair over? And why did they flip it over? Was it in a fit of rage? I ended up naming the chair piece after the show, Facts Are Bigger in the Dark. Eventually, one day, I’d really love to do a show where all the drawings are displayed on the backs or on the undersides of furniture, and none are on the walls.

Figure 11: Z.T. Nguyễn, Facts Are Bigger in the Dark, squid ink, graphite, colored pencil, and acrylic on letter-sized sheet of paper; overturned found chair, 23.5 x 36 x 16 inches (59.69 x 91.44 x 40.64 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Z.T. Nguyễn

But the drawing itself for this piece was made with squid ink, actually, which I feel was a significant choice for me. Fun fact: squid ink is actually the original sepia ink! I guess it's no longer a standard art material, though, because I had to get it from a culinary website, since it's more commonly used to dye food in Italian and Japanese cuisines. I really wanted to make a drawing using the materiality of fear. And since squids and octopuses and cuttlefish emit ink to escape danger, it was kinda perfect. It smells really, really bad, though—like, super fishy—[laughs] and it's a really difficult material to work with, so the drippy, messy markmaking just emerged as I drew it. Graphite is such a controlled medium in comparison, especially because I mostly use mechanical pencils, so it was a bit of a challenge for me to get it to look decent. It even works differently than other kinds of ink, like India ink—it just sits on top of the paper and doesn't absorb into it as easily.

LX: That makes sense that it’d be viscous. But there’s also something about the ink itself, as a kind of self-protective mechanism. Even with squid, it’s about defense, survival.

ZTN: Right, like that's part of its defense; it even resists my control over it. I had to learn to let go of my sense of control and ended up just spraying it with water so it could just drip all around the paper. And that ended up working really well! It was so much better when I let it do its own thing; it actually looked like the materiality of fear.

LX: When I saw the CRT TV and single chair, I subconsciously thought of Warhol’s Electric Chair. Was that your intention, or were you more focused on evoking absence?

Figure 12: Andy Warhol, Electric Chair, 1971, screenprint, sheet: 35 7/16 x 47 ⅞ inches (90 x 121.6 cm). Edition 192/250 | 50 APs. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; gift of Peter M. Brant © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./ Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York (73.92.3) https://whitney.org/collection/works/7335

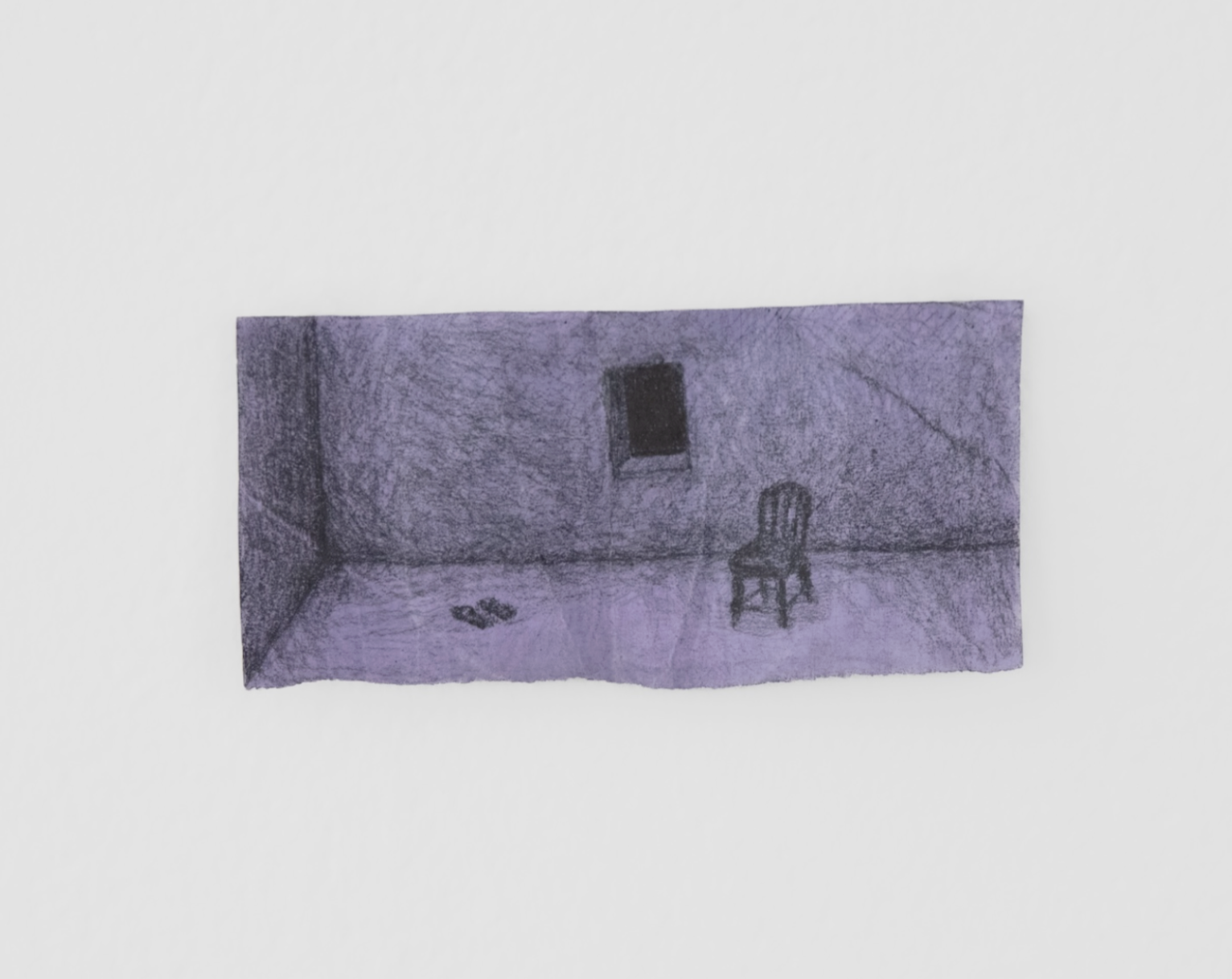

ZTN: It wasn't my intention, but I'm glad you thought of that because of its political indications. I personally was more focused on absence and a kind of unfriendly domestic space, which I mentioned earlier with Watching. But I think it's best exemplified in the smallest drawing in the show, which is less than two inches on its shortest side. Its title is Home, and I think the significance of its impact is in its small size versus some of the bodies in other drawings around it that are larger than life. So, what does it mean for this space—this home, this place of supposed comfort and rest—to be so tiny that a body could never fit into it? What does someone do when their own home is too small for them?

Figure 13: Z.T. Nguyễn, Home, graphite and acrylic on paper, 3.9 x 1.9 inches (9.90 x 4.82 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist and Pat Garcia © Z.T. Nguyễn and Pat Garcia

LX: Did you ever feel that way while making this, like physically out of place or out of sync? I’m thinking about how our bodies sometimes feel out of space, and whether that influenced the scale of your work.

ZTN: I think so. Those feelings, for me, come from being queer, being Southeast Asian, ongoing politics, all of the things we've been talking about so far. Not belonging and not being heard. Interestingly, for a work that has so much of my personal strife wrapped up into its ideation, I think it’s the smallest finished artwork I've ever made. I wonder what that means [laughs].

Figure 14: Z.T. Nguyễn, Almost, graphite, colored pencil, soft pastel, and acrylic on letter-sized sheets of paper, 172 x 32.5 inches (436.88 x 82.55 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Z.T. Nguyen

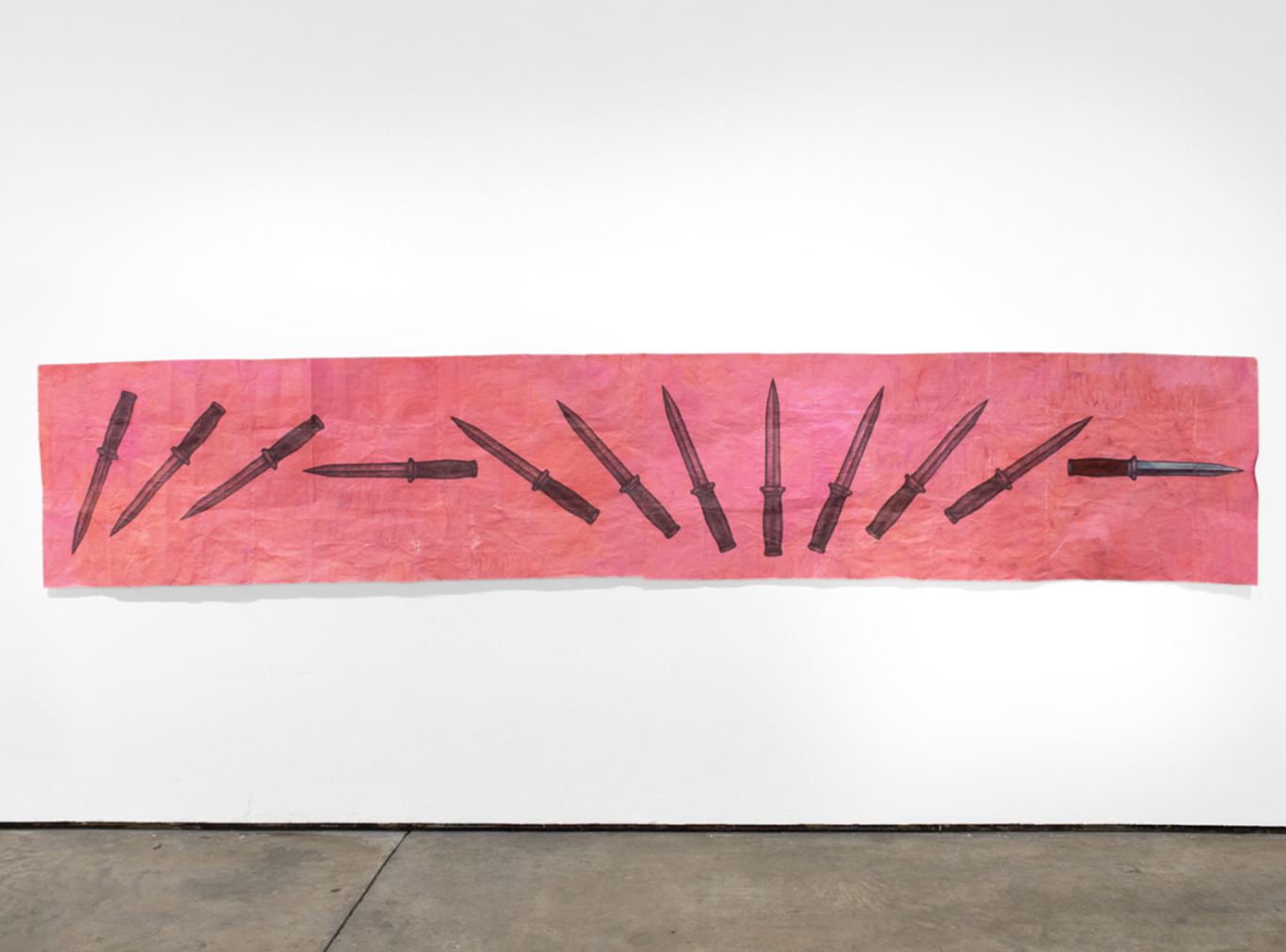

LXM: Fascinating, tell me more about Almost.

ZTN: Funny that we're following the smallest work in the show with this piece, which I think might be the largest. I had to watch a lot of slow-motion videos of knife throwers to make this drawing; I was studying how knives spin through the air, so that the drawing could imply that same movement. The process of drawing the same knife over and over again as it spins through space was really tedious and time-consuming, but I consider that to be part of the potential energy of the drawing and the effect it has on a viewer. The whole thing is about fourteen-and-a-half feet long—the longest single dimension out of all the works in the show—but it all comes down to the moment where the rightmost edge puckers inwards to meet the tip of the rightmost knife: the only one in the drawing that's fully rendered in color with soft pastel. That edge shifts into a deeper magenta or red, almost like it's bruising as it strains itself to meet the blade, like it's asking to be punctured. It’s about that split second before it hits—that tiny space between the tip of the knife and the edge of the paper.

LX: I love that undulating edge. Is it meant to suggest puncturing skin or a specific body part?

Figure 15: Z.T. Nguyễn, Almost (detail), graphite, colored pencil, soft pastel, and acrylic on letter-sized sheets of paper, 172 x 32.5 inches (436.88 x 82.55 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Z.T. Nguyen

ZTN: Not necessarily, but I'm not opposed to that interpretation at all. I wanted the pink to feel bodily, but not strictly skin-like. More like the layers beneath the skin's surface—something flesh-like, almost like the color of muscular diagrams in science or anatomy textbooks, but maybe more vibrant or urgent than that. Similarly to how I was talking about color before, this pink is also about its relationship to red: it's a softer, less powerful version of it. Like, think of this pink as the potential energy of anticipation, and the red edge as the intensity of rupture. In a lot of ways, I think this work was the centerpiece of the whole show, even though I also think it's the most different from the rest of the works… it's like this one piece summarizes the emotional qualities that the others achieve collectively.

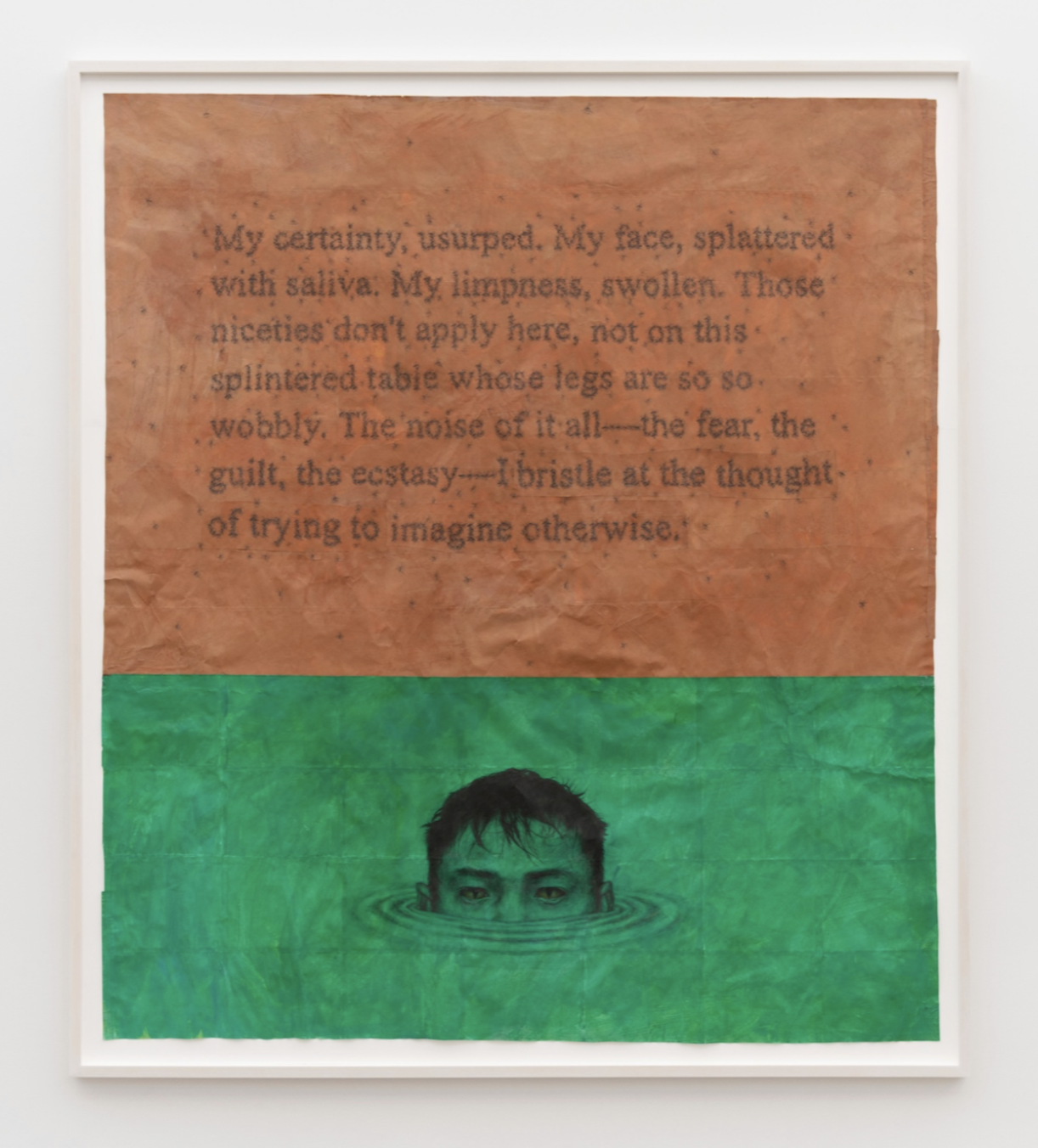

LX: Fascinating. Before we end, let's move on to your Perrotin work and its text.

ZTN: Ah, yes. This one is my baby [laughs]! Or, like my big baby. They’re all my babies, but I think I'm still really attached to this one because it was the last piece that I made at Yale. I wrote the text for it myself, but originally it was for this creative writing class that I was lucky enough to have taken in my last semester. It was a prose poem I wrote for an assignment, but I figured it could actually work really well as a drawing. Let me read it to you:

My certainty, usurped. My face, splattered with saliva. My limpness, swollen. Those niceties don't apply here, not on this splintered table whose legs are so so wobbly. The noise of it all—the fear, the guilt, the ecstasy—I bristle at the thought of trying to imagine it otherwise.

It took a massive effort on my part to draw the mosquito-text, which I did over the course of a few days. I think I must’ve pulled two at least all-nighters to get it done before my last final critique at Yale? I was also preparing for surgery during that time so I was in a lot of physical pain and discomfort, which had been going on for, like, two months at that point. It was a brutal last semester; I don't know why I did all that [laughs]. But I'm kinda glad it all worked out, since I'm actually really pleased with the result. I kept thinking about how fragile, how impossible it would be for mosquitoes to come together to spell words that have meaning like this. But also, if it actually happened, I thought about how painstakingly brief it would last before dissolving. Kinda like Mosquito Star, which we discussed earlier, but on a much more ambitious scale.

LX: Wait, so the writing is actually tiny drawings of mosquitoes?

ZTN: Yeah! The words are made up of about 2,500 individually-drawn mosquitoes. I think I'm really interested in the meaning of the words, of the language, but within the context of the mosquitoes. Like, yes, it is about the homoerotic and masochistic implications of the words themselves, but, it's contained by the brevity of a moment when everything suddenly aligns and becomes clear, only for it to scatter away from you. Like, how precarious and fragile and fleeting a split second of clarity can be, and the desire that you have to hold onto it, or to stretch it out. That's what this drawing is. I see that in the lower green portion, too, with the head rising from the water, but I think a lot of its significance does lie in the upper brown portion, in the mosquito-text. I wrote about it in an Instagram post, which articulates it a bit better than how I'm explaining it right now, I think. I can read it for you:

The words in A sort of delicious terror are made up of roughly 2,500 individually hand-drawn mosquitoes in flight—a swarm that some might describe as precarious, or maybe even threatening. It's a motif I've invoked several times in the past few years of drawing.

But I think I'm (slightly) less interested in the precarity of the mosquitoes themselves here, and more interested in the precarity of so many moving parts. If mosquitoes ever actually converged to form language like this, any kind of meaning that's conveyed would be so brief it would only last an instant—and then in the next, the mosquitoes would dissipate back into chaos. This drawing is largely about holding that instant, the moment where things align against all odds before falling apart again. It's about how we remind ourselves of the moments that are profoundly meaningful and erotic and liberating and humbling and radical and necessary, especially amidst genocide, fear-mongering, and violence. If there's one thing I’ve had to do the most during my MFA at Yale, it was maintaining and tending to these moments continuously alongside engagement and action as times and circumstances changed and warped.

Figure 16: Z.T. Nguyễn, A sort of delicious terror, graphite, colored pencil, and acrylic on letter-sized sheets of paper, 83 x 73 inches (unframed) (210 x 185.42 cm [unframed]). Photo: courtesy the artist, Perrotin Gallery, and Guillaume Ziccarelli © Z.T. Nguyễn and Perrotin

Queerness and queer desire often make up the content or subject matter of my work, but it’s always driven by themes of liberation and revolution, even if it's in a way that isn't obvious. I guess it's because I see those things as inherently linked. In this particular drawing, queerness is really anchored in the text, in the meaning of the language itself. It describes a sexual encounter or intimate moment that is gross and masochistic and maybe even scary but in a way that the narrator actually really desires. But the fact that it's made of mosquitoes and so temporary—that's the part that feels liberatory to me, or rather, that this drawing has frozen this moment in place and pinned it down feels liberatory. It's like holding onto a moment of desire forever, a moment that was supposed to have just come and gone. I think I see it as analogous to holding onto moments of meaning and collective power.

Radical moments, not necessarily of sexual desire, but of the desire for real change, moments that are actively being suppressed. In our current political climate, I was really thinking about what it means for me to graduate from an institution like Yale and what it means for me to show my work at a gallery like Perrotin, and what I wanted my work to say or to evoke. What can I even offer at a time like this? What does it mean to be a student artist, or a recently graduated artist, while ICE raids are happening on campus and abducting my peers? While we're being doxxed by far right groups for opposing war and genocide, while there are crackdowns on protests, while faculty members are being censored? While entire curricula about feminism, queer theory, race, or diasporic perspectives are being masked or altered or erased altogether? It's an impossible thing to balance.

LX: “Splattered with saliva” also conjures the splattering of blood to me.

ZTN: Interesting. In the context of blood of a bodily fluid that might result from real violence, I think this idea of holding onto a pivotal moment changes. It becomes more of a moment of not backing down and not forgetting, rather than a moment of desire or ecstasy. I think that shift makes those moments where desire and violence come close together—where they almost even intersect—really important to this work. It's like a reminder that even if the moments we freeze in place and hold onto stem from desire, we ultimately need to see change through to the very end.

Z.T. Nguyễn

Z.T. Nguyễn (b. 1997, Silver Spring, MD) is an artist based between Maryland and New York. In 2025, he had his debut solo exhibition at island, New York. His work has been included in group exhibitions at Perrotin, New York; Klaus von Nichtssagend, New York; Asia Art Archive in America, Brooklyn; and Vincom Center for Contemporary Art, Hà Nội; among others. He has participated in residencies and fellowships at Textile Arts Center, Brooklyn; The Alternative Art School & MAIIAM Contemporary Art Museum, online; and Asia Art Archive in America. Nguyen received his BFA in Painting from Rhode Island School of Design in 2019 and his MFA in Painting and Printmaking from Yale School of Art in 2025.