The Loves I Have Known: In Conversation with Louise Mandumbwa

Louise Mandumbwa contends with her diasporic experience in her multimedia practice. Lara Xenia speaks with the artist about her botanical research, material exploration, and intergenerational knowledge.

Figure 1: Installation view of The Loves I Have Known, 2025, paper, canvas, graphite, ink and charcoal, 60 x 46.5 inches (152.4 x 118.11 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist, Pat Garcia, and Zeshan Ahmed © Louise Mandumbwa

Lara Xenia: What was the first piece of art you've ever stared at?

Louise Mandumbwa: I grew up in a really small town that didn't have big cultural museums or institutions, so a lot of my first interactions with artworks were through ones I’d find online or in the pages of books. It wasn't until I was a young adult, like 18 or 19, that I experienced one of those seminal works in person. In the Crystal Bridges Museum in Northwest Arkansas, I turned the corner in the contemporary wing and was met by a Barkley Hendricks painting. Four figures in white, and a lady that had a little afro. It was an image I'd revisited often. Seeing it in person stopped me in my tracks as a work I had been struck by as a younger person, now directly in front of me.

Figure 2: Barkley Hendricks, What’s Going On, 1974, oil, acrylic, and magna on cotton canvas, 65 ¾ x 83 ¾ inches (167 x 212.7 cm). Photo: courtesy the Estate of Barkley Hendricks

LX: I love Hendricks. Was that the first time you went to a museum here? How did it compare to the museums and art spaces you had access to before?

LM: It was. I came to the U.S. specifically for my higher education when I was 18, and was fortunate that I had the opportunity to visit major art institutions in my few years here. Prior, I had spent most of my years in Francistown, Botswana. It was a sweet, nondescript town, which I called home. What Francistown didn’t have in abundance, however, was a robust collection of formal art institutions.

LX: Is that partially what incentivized you to study here in the States?

LM: Oh definitely. I set my sights on art school in the U.S. at 18. I dreamt of attending SCAD, but I soon learned that scholarships for international students were scarce. Family friends in Arkansas offered guidance and a home near a local community college. Thanks to their generosity, I came here and earned an Associate’s degree in Graphic Design. I later transferred to the University of Central Arkansas, where I completed a BFA in Painting and discovered printmaking. It profoundly transformed the way I think about process, repetition, and material. After graduating, I interned at a gallery, then moved to Virginia to focus on my portfolio and graduate school applications. I was accepted into my dream program, moved to New Haven in 2022, and graduated in 2024. Each stage of that path continues to shape the way I approach my work.

LX: Your portraits are stunningly detailed, and it’s quite a departure from your recent body of work. Where is it situated in your practice?

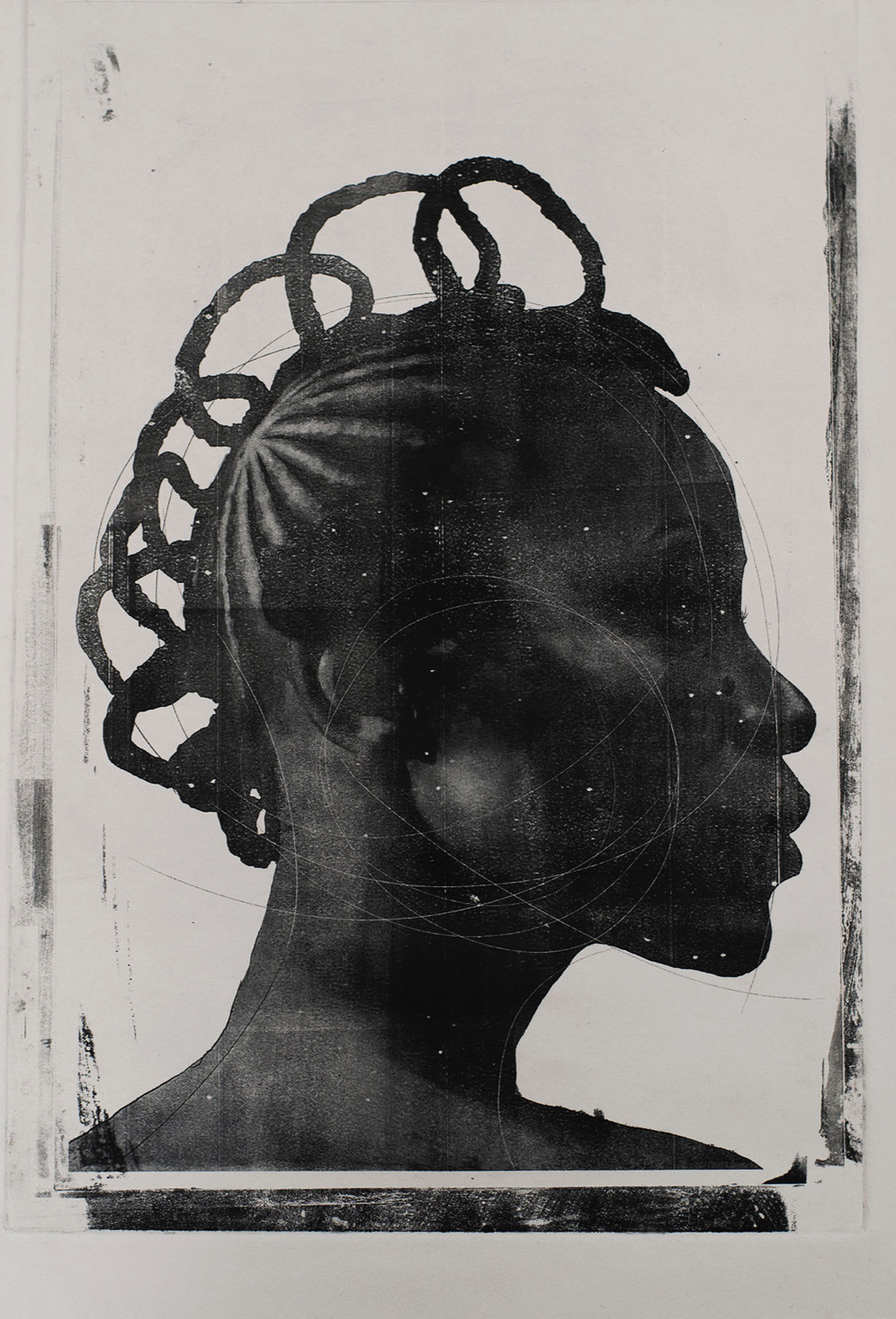

Figure 3: Louise Mandumbwa, Good Immigrant, proto plate print, 2019, 17 x 11 inches (43.18 x 27.94 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Louise Mandumbwa

LM: My early practice was focused on technical execution. Being too shy to ask others to sit for me, I turned to the work of photographers I felt were making compelling work, using some of those images as references for pieces that helped me refine my visual voice. The muse for this work was a South African artist, Kwena Baloyi. Throughout that exploration I progressively became interested in how ranging mediums handled control, chance, and repetition differently. Painting always offered a sense of precision and intention, and printmaking refused that control. The unpredictability of the process revealed something I couldn’t achieve through painting alone.

I discovered pronto plate lithography, which uses polyester sheets instead of stone. Unlike traditional litho, the plate deteriorates quickly, producing only a few prints before the image begins to break down. Each pull erases a little more information. That material decay and erosion became a metaphor for memory itself and its unpredictability in fading. We don’t choose what we forget, and we rarely notice when the image begins to disappear. This process allowed me to explore absence and loss not as failures but as forms of meaning, when what is missing carries as much weight as what remains.

In many ways it was through the discoveries of this process that my work began to focus more on memory and a perspective shaped by my experience as the daughter, and granddaughter of immigrants. When I started photographing people close to me, I realized that the totality I sought in painting did not align with how memory actually works. I was aware of gaps in my own family history; how stories were half-told or lost. Memory, at least as I’ve experienced it, is often fleeting, fragmentary and pieced together to make up an approximation.

LX: I’m especially drawn to the multi-faceted, trace-like elements in your work. Were the figures in your portraits based on people you were personally connected with at the time?

LM: Absolutely. People often asked where I was from when I first moved to the U.S. and I noticed that my answers were never about geography or infrastructure, but about the people I knew. I understood places through the people who shaped them for me. In my early work, around 18 or 19, I began painting portraits based on photographs I had taken myself. Each work was tied to a personal story.

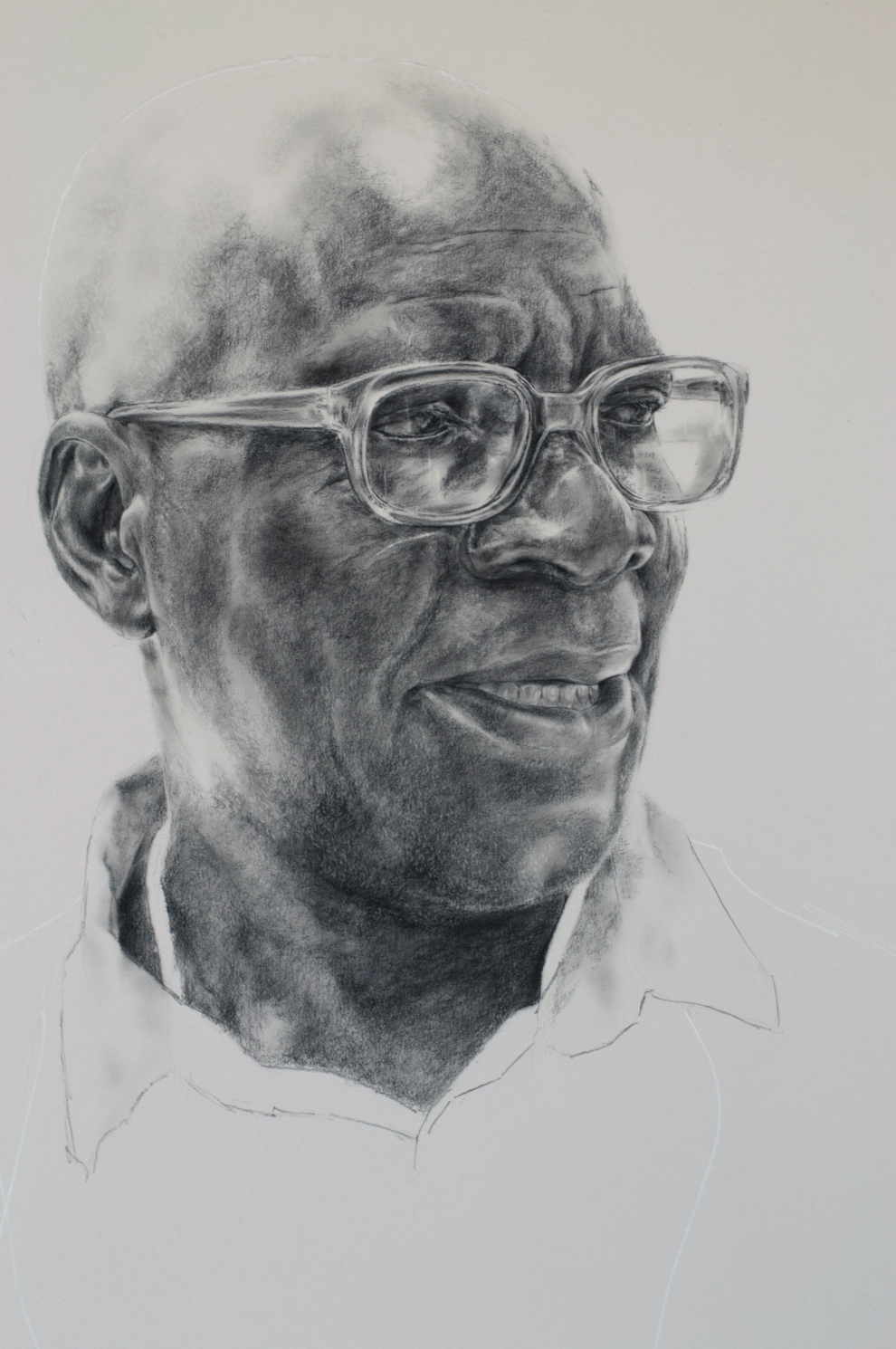

Figure 4: Louise Mandumbwa, Jacob, 2021, charcoal on paper, 30 x 22 inches (76.2 x 55.88 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Louise Mandumbwa

Figure 5: Louise Mandumbwa, Rre Dodzi, 2021, charcoal on paper, 30 x 22 inches (76.2 x 55.88 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Louise Mandumbwa

One portrait shows Jacob, the security guard at my high school, who greeted me every morning for six years, and another depicts an older man named Rre Dodzi or Mr. Dodzi, who watched me grow up in my childhood neighborhood. Those early portraits became an archive of belonging, and a way to map my home through human connection. I have never had a strong recall for faces, but through painting and drawing, I found that I remembered them more clearly. These drawings became a way to commit their presence to memory and to show people where I’m from.

LX: Fascinating. What led you to pursue making works about sugarcane?

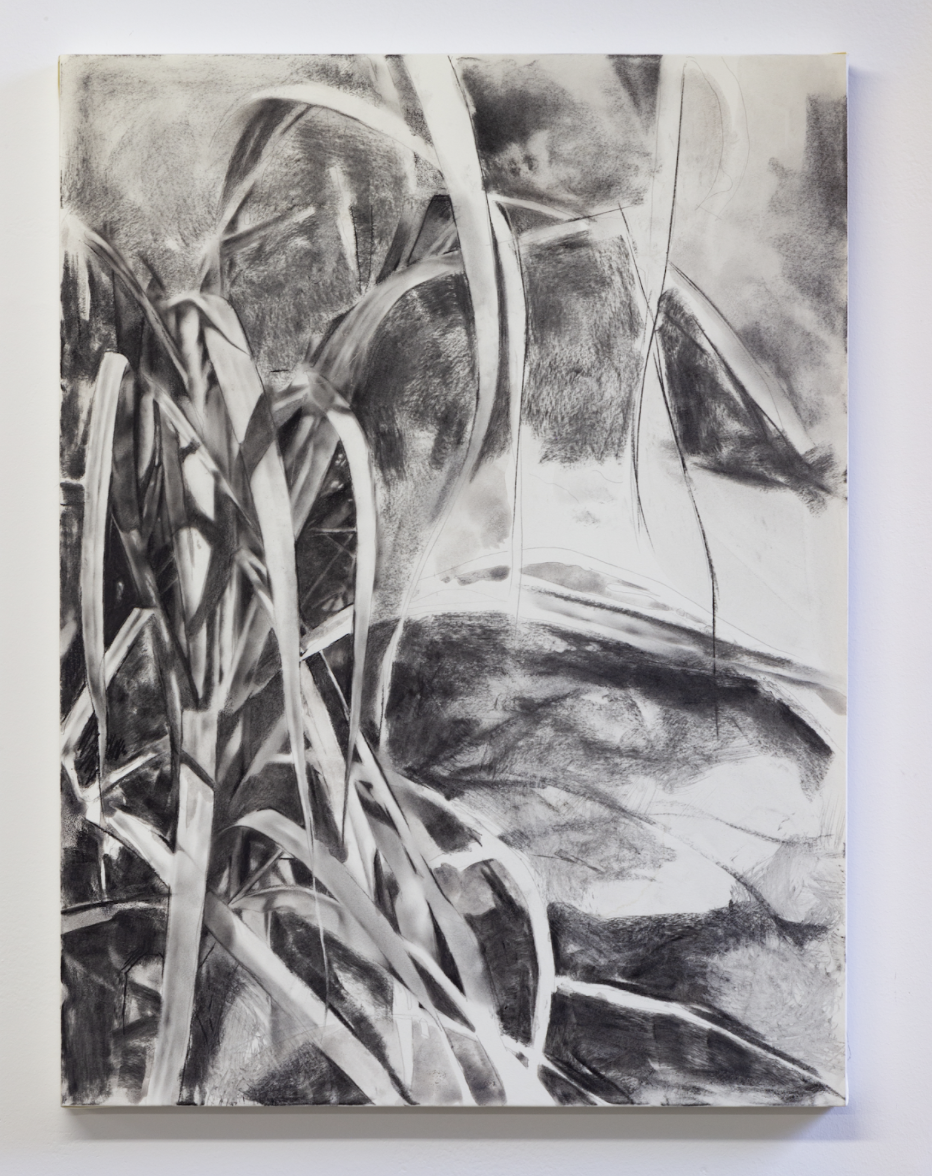

Figure 6: Installation view of They stole the sweet away, 2023, charcoal on paper; 24 x 18 inches (60.96 x 45.72 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist and Pat Garcia

Figure 7: Configuration 1, 2023, paper, canvas, acrylic, and charcoal, 24 x 18 inches (60.96 x 45.72 cm); 36 x 12 inches (91.44 x 30.48 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist and Zeshan Ahmed

LM: In grad school, I began rethinking how I mapped relationships. I’d always understood “places” through the relational, but wanted to make touch points that allow others to enter the work without needing my full personal history. That led me to think about the gardens I grew up around, like my grandmother’s home, which had sugarcane, guavas, and plants that she’d tend to. I began to see gardens as parallels to relationships; always in flux or nurtured and maintained overtime. My grandmother’s and mother’s gardens were constantly changing, but certain trees remained, and reflected their degree of care.

Those early portraits became an archive of belonging, and a way to map my home through human connection.

Figure 8: Installation view of Configuration 1C, 2023, paper, canvas and charcoal, 24 x 18 inches (60.96 x 45.72 cm); 36 x 12 inches (91.44 x 30.48 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist and Pat Garcia

When I no longer had access to the people who shaped those memories, I found a similar sense of connection in plants that existed elsewhere. Sugarcane grows in many regions, as does yucca or cassava. Encountering them revealed how plants also trace histories of movement. I learned that cassava, which I had always associated with the Congo where my grandmother grew up, was introduced there by the Portuguese because of its resilience to drought. I was fascinated by how plants like cassava and Bougainvillea appeared across continents, and quietly mapped diasporic movement. Their presence is not about invasion, but about contact, exchange, and transformation. These plants hold the intertwined histories of place, migration, and adaption, much like the people who care for them.

LX: That's so interesting. Do you usually combine yucca with other plants in these works? What inspired you to layer these elements, and what is the text embedded above it?

LM: Much of the text begins as annotations made directly on my paintings and drawings. I used to write on the surface itself, then copy the text into a field journal before erasing it. The writing often takes the form of short poetics and fragments that respond to what I’m thinking about while I work. Now, I write on transparent sticky notes that I place in my journal. The clear paper mirrors the studio process, and layers text and image in a way that feels both visible and ephemeral. The fragmentation in my work grew out of realizing that I was trying to capture something total in a painting and always falling short. I began to see that failure as more honest. Memory itself is partial; some things are recalled through language, and others are through image, color, or material association. By bringing those fragments together, like what can be named clearly, what can only be felt, I try to create a visual language that reflects how memory actually lives in the body. It is less about precision and more about assembling what remains, by allowing language, image, and material to speak to one another.

Figure 9: Untitled [detail], 2023, paper, canvas and charcoal, liquid graphite, 36 x 30 inches (91.44 x 76.2 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist

LX: I’m interested in how you fragment elements across the canvas and combine different surfaces within one composition like wood or other supports. The variation in surface gives the work a tactility, and its own rhythm and weight.

LM: Materially, I was thinking about home, and what it means when it’s not a physical structure. I had been challenged that my work rarely depicted an interior space, as something that could be visually read as “home.” I resisted that, because I believe you can be dispossessed of a building in a way you cannot be dispossessed of a relationship. I began to explore how material could point toward that idea. I used concrete, wood, glass, and eventually Plexiglas, which would not shatter. I also worked with aluminium and steel, which are used to construct homes in Zambia, Botswana, and much of Sub-Saharan Africa. I wanted to bring that vocabulary of materials into my work, even if the image itself did not depict a house. For me, these materials carry the presence of home through its material vocabulary, with its texture, resilience, and weight, even when the form itself is absent.

Their presence is not about invasion, but about contact, exchange, and transformation. These plants hold the intertwined histories of place, migration, and adaption, much like the people who care for them.

Figure 8: Louise Mandumbwa, Configuration 1, 2023, paper, canvas, concrete, plexiglass, acrylic, gouache and charcoal, 12 x 12 inches (30.48 x 30.48 cm); 22.5 x 19 inches (57.15 x 48.26 cm); 16 x 6 inches (40.64 x 15.24 cm); 24 x 18 inches (60.96 x 45.72 cm); 36 x 12 inches (91.44 x 30.48 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist and Pat Garcia

LX: I’m really interested in how you fragment the composition and layer the plants in the foreground then echo their remnants in the background, as if they exist in another space. You also use yellow often. Is that hue somehow reminiscent of home for you or does it carry a particular connection for you?

I try to create a visual language that reflects how memory actually lives in the body.

LM: That’s exactly it! I had been writing about what home might feel like, look like if it had a color, a taste, or a texture. I wanted to think more critically about my relationship with color, rather than just working from photographs. In my notes, I wrote about the time of day when I would come home and stand in my mother’s garden. I would close my eyes and feel the light shifting as the sun set. Because we lived near the tropics, the sunsets were long and warm, and filled with yellows and oranges that seemed to filter through my eyelids. When I think of home, that light is what returns to me. If home had a color, it would be that warm, glowing yellow that lingers just before dusk.

LX: It’s cool that you vary the scale and height of the works. It definitely changes how the viewer relates to them and walks through space.

LM: Yes, and with the botanical pieces, I’m interested in placing them at the height of their real world referent, swaying overhead, or close to the ground. It’s not a literal replication, but I want viewers to experience the work in the spatial register where it exists in nature.

Figure 11: Louise Mandumbwa, Something to Hold Onto, 2024, cast aluminum and carborundum, dimensions variable. Photo: courtesy the artist and Pat Garcia © Louise Mandumbwa

Figure 12: Louise Mandumbwa, Something to Hold Onto, 2024, cast aluminum and carborundum, dimensions variable. Photo: courtesy the artist and Pat Garcia © Louise Mandumbwa

LX: I also wanted to ask about these barren tree-like forms. Is that actual soil in the piece, or a material meant to emulate it?

LM: It is meant to emulate soil. The material itself is carborundum, which in printmaking is used to reset a lithographic stone by removing an image. It has a texture similar to sandpaper in powdered form. I was drawn to it because it holds a kind of material memory, shifting an image from something perceivable back to pure matter. The sticks are cast aluminium. Between my first and second year of graduate school, I visited my father's hometown near the Angolan border in northern Zambia, Chavuma, a place I had never been before. What struck me most was the prevalence of yucca, a plant I had always associated with my grandmother and with the Congo. My family’s roots extend into Angola as well, and yucca is part of daily life there. Because I was already making drawings of plants, I began to imagine an archival garden. I collected cuttings of yucca from my grandmother’s home, casting them in aluminium, and created the first iteration of what I hope will grow into a more expansive living archive.

LX: That’s beautiful. How did this one come about? [Gestures to painting]

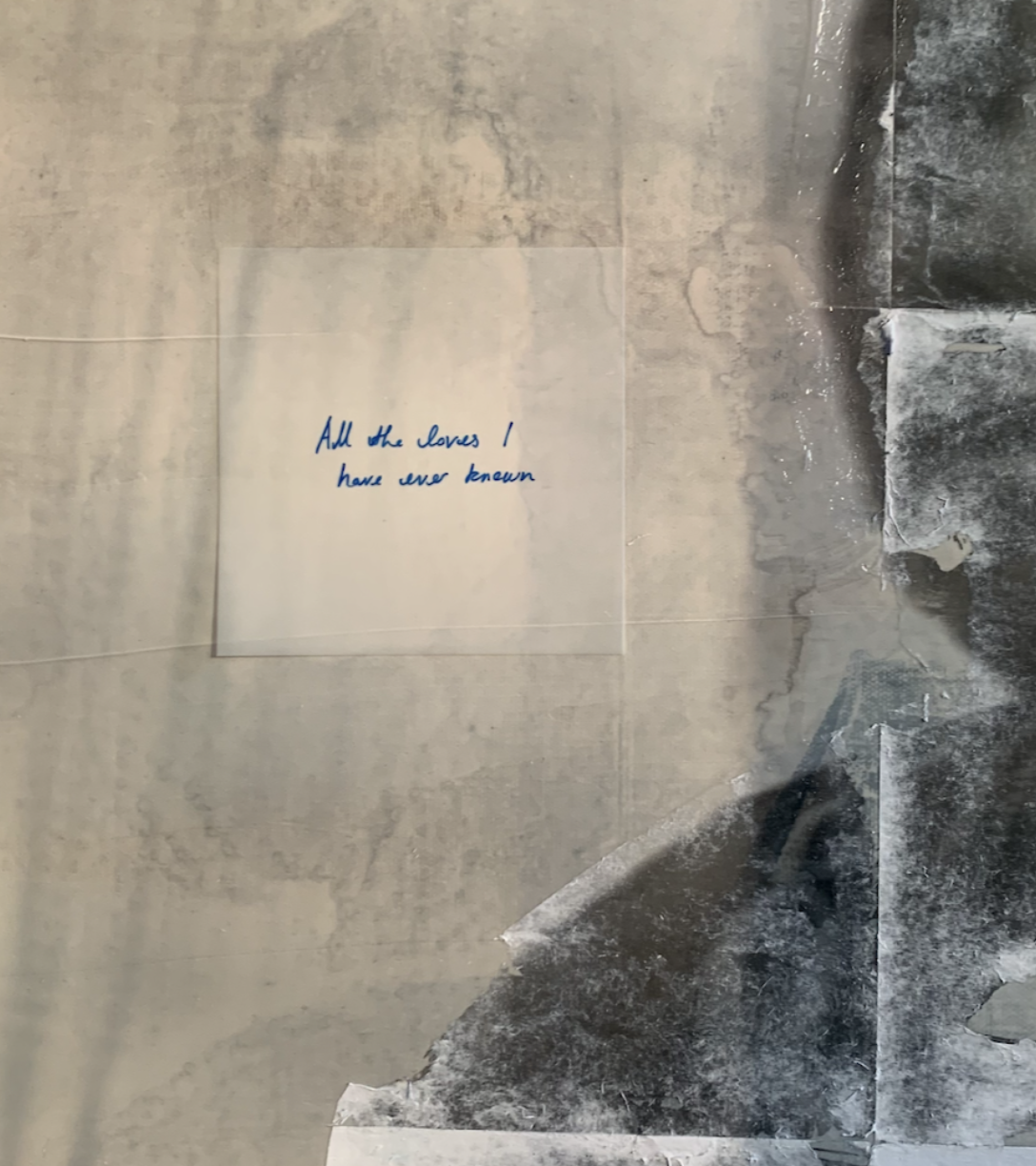

LM: Towards the end of my graduate program, I began wondering what happens when a person’s likeness becomes imperceptible, or begins to dissolve. Around the same time, I was asked whether I had considered making a self-portrait, and how I felt about representing myself in that way. That really opened up a new line of thinking for me. I believe it’s called The loves I have known.

Figure 13: Louise Mandumbwa, The loves I have ever known [detail], 2024, paper, canvas, graphite, ink and charcoal, 60 x 46.5 inches (152.4 x 118.11 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Louise Mandumbwa

Figure 14: Louise Mandumbwa, The loves I have known, 2024, paper, canvas, graphite, ink and charcoal, 60 x 46.5 inches (152.4 x 118.11 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist, Pat Garcia, and Zeshan Ahmed © Louise Mandumbwa

I have been writing about embodied memories and the idea that what you need to know about me may not be my likeness at all, but the things I love. I think about the sweetness of sugarcane and the memory of my hands at work and wanted to create a self-portrait that leaned into that, where the clearest element is not my face but the sugarcane I have written about so often. I am also working on an artist’s book that gathers these texts and fragments of writing. Many of my works share titles with the poems or essays that accompany them, to offer another entry point into the visual pieces. In this particular work, the figure is me, but I am almost invisible. What remains visible is the sugarcane, the foundational memory from my grandmother’s yard. By seeing that, rather than my face, you might understand something more essential about who I am.

The post-it you see there says, “What is possible in the illegible image? What exists in the gaps of the archive? In the failed transcription?”

LX: I didn’t initially realize the figure was actually you [laughs]. Why did you choose a three-quarter view that turns the gaze away from the viewer?

LM: I feel comfortable looking directly at the viewer, but early in my practice I made several front-facing portraits and later found the experience of seeing them together in a gallery unsettling. I felt like being stared at from every direction. That moment made me reconsider the gaze in my work. I began to think more intentionally about how awareness and intimacy operate between the subject and the viewer. The three-quarter and profile poses allow for a sense of interiority, and a space that feels more reflective than direct. I still love the intimacy of a frontal gaze but I now prefer when that closeness emerges through the viewer’s act of searching rather than through immediate eye contact.

What is possible in the illegible image? What exists in the gaps of the archive? In the failed transcription?

LX: I like that your face isn’t immediately visible in the piece. At first, I viewed the figure as almost statuesque. How did you achieve that beautiful blurred effect?

LM: I have been interested in collapsing mediums and letting printmaking, drawing, and painting overlap. The base of the work is a print made with materials that blur those boundaries, like liquid graphite, liquid charcoal, and silkscreen mediums. These combinations allow me to paint and print with what would usually be used to draw. In this piece, I layered paper over the canvas surface, pressed fragments of poetry onto it, and then rubbed them away by hand. The gesture created both erasure and felt revelatory like a record of my touch. I kept thinking about how we come to know the world. As children, we learn through our senses, through the feeling of things, and later language begins to narrow that way of knowing. Working with my hands allows me to return to that tactile understanding and let meaning show through touch rather than through language alone.

LX: As you describe the work, I can almost sense the sound and movement of the leaves, as if you had combed your hand through it. Do you have a robust archive at home of family photos to draw upon?

LM: I think my interest in archives comes from the lack of an abundance of documentation of my family’s history of migration. My parents moved from Zambia to Botswana, and my grandparents moved from the Congo and Angola to Zambia. With every migration, pieces of our story were lost. Even within one town, my family moved several times, and with each successive shift gaps widened or were created anew. There were very few family photographs, and each time I asked about one, I was met with a best guess of which relative might have it. Over time, I realized I was trying to build an archive for myself, to fill in what was missing. Language has also shaped this distance.

I only speak English, and my last living grandparent does not. Our conversations always require a third person, which reminds me of how much is untranslatable. Some meanings can never be fully carried over, no matter how carefully they are explained. That awareness deepened my interest in tactility. I know my grandmother less through her words than through the texture of her world, like the taste of her cooking, the things her hands made, the garden she nurtured…she once knitted and crocheted constantly, so her tenderness communicated entirely through touch. During the pandemic, when she was unwell and I was far away, I began to think about what I could still hold of her. I realized that my work grows from that same impulse of wanting to honor what remains when language fails, and trace love and memory through what is felt rather than spoken.

LX: Is Tell Me Something True a depiction of you with your grandma?

Figure 14: Louise Mandumbwa, Tell me something true, 2024, acrylic and oil on canvas, gouache and oil on paper, 20 x 16 inches (36 x 48 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist, Pat Garcia, and Zeshan Ahmed © Louise Mandumbwa

LM: This painting is of my younger sister with two of my great aunts. It was taken during the trip when we visited my father’s home village. That visit felt like finding pieces of an answer I had been searching for. My father left the village when he was about ten and did not return until he was in his forties. When we visited together in 2023, he shared stories I had grown up hearing, but my great aunts, Margaret and Nama, remembered them differently. Their recollections recontextualized everything. I realized that my understanding of this place had been built on secondhand memories recounted decades later. That trip also revealed something about my own name.

The botanical piece beside the photograph refers to my maiden name, Mandumbwa, which I learned comes from the Ndumbwa tree, native to that region. The word itself, Mandumbwa, refers to the fruit of that tree. My family settled near the groove where those trees grew, and the name became tied to the land. For me, that discovery elucidates how a name can serve as a kind of map for locating both family histories and belonging within a landscape.

LX: That’s so interesting. I love how deeply you engage with theory and the natural world. It’s rare to see. The botanical research in your work is such a beautiful entry point, especially in relation to trade and movement. I’m also curious about your work End Notes.

Figure 15: Louise Mandumbwa, End notes, 2024, concrete, wheat paste and newsprint, 14 x 66 x 3 inches (35.56 x 167.64 x 7.62 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist, Pat Garcia, and Zeshan Ahmed © Louise Mandumbwa

LM: End Notes is a cast concrete work that grew from my interest in how information circulates across different places. In the United States, zine culture carries a sense of accessibility and exchange. In southern Africa, that same impulse often takes shape through printed pages wheat-pasted on concrete walls outside homes and shops, where they weather, layer, and form an informal public archive. I wanted to create an artist book that felt rooted in that context. I learned letterpress printing, traditional bookbinding techniques and looked at self publishing methods, but concrete felt closer to the material reality of how ideas move where I am from. I cast a heavy slab, applied fragments of my poetry to its surface, and then weathered the paper away. What remains are only traces like page numbers, faint marks, and remnants of language. The piece slows the act of reading and asks what knowledge might live in what has been erased.

LX: How heavy is it, and how did you manage to hang that piece?

LM: With difficulty [laughs]. The piece is about four-and-a-half inches deep, with an empty cavity in the back and an inset forty-five-degree French cleat inside. I wanted the piece installed slightly lower than the rest of the paintings, since it is called End Notes and was meant to feel a little offset. During installation, we discovered the wall was uneven and it turned out to be a false wall. We finally had to move it to another spot at midnight. By the end, I just said, “If it’s on the wall, I’m happy.” That exhausting experience added to the work honestly [laughter].

LX: As an “end note” question, if you could imagine your ideal solo show, what would it look like, or where would it be?

LM: I’ve imagined an exhibition built around iteration and memory. There’s a work I made called All Artist Proofs that features many small faces, some of which are clear, some of which are blurred, and some are almost gone. I love the idea of showing two related works in different rooms, where each holds part of the image. You would have to carry the memory of one as you walk to the next, piecing them together in your mind. My dream show would ask the viewer not just to look, but to remember and to connect the fragments kind of like breadcrumbs. I imagine one room as a living garden filled with sugarcane, yucca, and plants from different places I’ve called home, like a hybrid garden of memory and geography. There’d be an artist book with page numbers or fragments that guide you toward other parts of the exhibition.

Photo: Arielle Gray

Louise Mandumbwa

Louise Mandumbwa (born 1996, Francistown, Botswana) is an artist working in painting, printmaking and drawing to explore ideations of home, figurative and botanical works. Her practice is a counter mapping endeavor examining the ranging registers or memory through material exploration, the illegible image and failed translation. An immigrant artist her works revisits sites of both familial and diasporic history to and appends them with affect and the anecdotal. Mandumbwa holds an MFA in Painting and Printmaking from Yale university as well as a BFA in Painting from the University of Central Arkansas. Her work has been included in recent group exhibitions at Sakhile&Me (Frankfurt, DE, 2025), Chili Art Projects (London, UK 2024), Spurs Gallery (Beijing, CN), David Castillo (Miami, FL), The Wright Museum (Detroit, MI) and Yossi Milo (New York, NY). She was a 2024 recipient of agrant from the Elizabeth Greenshield foundation and the Elizabeth Canfield Hicks award from Yale University. She has completed residencies at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture (2024), The Sam and Adele Golden Foundation for the Arts (New Berlin, NY 2022) and Visual Arts at Chautauqua Institution (Chautauqua, NY 2019) and Louise lives and works in New Haven, CT.

Instagram: @louise_mandumbwa