All Dolled Up: In Conversation with Amy Chasse

Amy Chasse investigates the paradoxes of inhabiting a human body. Chasse speaks with Lara Xenia about her upbringing, her interest in nihilism, and the many lives of her dolls.

Figure 1: Amy Chasse, Winner winner chicken dinner, 2024, archival pigment print, 22 x 17 inches (55.88 × 43.18 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Amy Chasse

Lara Xenia: Do you remember the first carnival you attended?

Amy Chasse: I grew up going to them every summer, so I’m not sure. I’m from a really rural area of Connecticut, so going to county fairs and carnivals was something we’d do with friends and family for the rides, fair food, and 4-H contests.

LX: What was life like before Yale?

AC: I studied Painting at Syracuse University in central New York. After graduating, I spent five years in the city and supported myself as an elementary school art teacher. I used to wake up extra early to paint in the corner of my room before school started, so I switched from oil to acrylic to avoid breathing in fumes [laughs]. I eventually leveled-up to a shared studio in Brooklyn. Three years into my time there, I left teaching to become a bartender to have more free time to paint during the day. I was producing a lot of work, but missed learning alongside other artists, so I ultimately applied to grad schools and landed at Yale.

LX: Wow, that’s really admirable; you’ve got tenacity. How has your practice evolved since starting your MFA?

AC: My practice has always been pretty interdisciplinary, but being in an MFA program has really pushed me in unexpected ways. I consider myself a painter, but I’ve become more interested in sculpture and installation. During my first semester at Yale, I took an intro to photography class where we were assigned to shoot 100 photos a week. I wanted to explore how placing my doll in real-world scenarios would affect how people perceive it. I brought the doll to my childhood home and staged a dinner scene with my mom at the kitchen table…I was especially interested in capturing her reaction. She was visibly disgusted by the doll, but still a good sport and went along with the shoot [laughs].

LX: What a fun concept for a photo series. Your mum also looks mildly mortified here [laughter].

Figure 2: Amy Chasse, Eating Together, 2o24, archival pigment print, 11 × 8.5 inches (27.94 × 21.59 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Amy Chasse

AC: [Laughs] She was. I wanted to capture her discomfort with the doll. The photos for me also explore personal family dynamics. I grew up with a single mom and it’s probably the most important and complex relationship in my life, so in some ways the photos are kind of diaristic.

I wanted to explore how placing my doll in real-world scenarios would affect how people perceive it.

LX: The baked potato is fun too. There’s a French phrase, “métro, boulot, dodo”, which sums up the experience of having to “commute, work, sleep.” And sometimes it’s just frozen or congelé veggies for dinner.

AC: Definitely. We’re an Irish family, so potatoes were always on the menu. I chose to include microwaveable veggies with melted cheese to highlight exactly what you are referring to. The domestic setting is important because it’s where we go to rest and retreat, but it’s porous to the realities and pressures of the outside world.

Figure 3: Amy Chasse, Living Room, 2024, archival pigment print, 11 x 8.5 inches (27.94 x 21.59 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Amy Chasse

LX: I love the stark contrast between your mom being on one end of the couch and your lab slumbering next to the doll in between them [laughs]. Was your mom genuinely freaked out, or did you stage her reaction to look that way?

AC: For that one, I told her, “This is the last photo—just one more.” I put the doll on the couch and said, “Just act normal, like you’re watching TV.” She looks perfect in this one. I love her body posture [laughs].

Figure 4: Jeff Wall, Pair of Interiors, 2018, two inkjet prints (diptych), each 81.75 × 59.88 inches (207.5 × 152 cm), edition of 3 + 1 AP. Photo: courtesy Gagosian © Jeff Wall

LX: Yeah, it looks staged. It vaguely reminds me of the awkward couch scenes by Jeff Wall.

AC: I love those. Those are great photographs. They almost feel painterly.

The domestic setting is important because it’s where we go to rest and retreat, but it’s porous to the realities and pressures of the outside world.

Figure 5: Amy Chasse, Resting, 2024, archival pigment print, 11 x 8.5 inches (27.94 x 21.59 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Amy Chasse

LX: Same. I really like this one because it's like a moment of rest and harps on the tradition of depicting individuals leisurely sitting in their salon. What inspired this particular pose and these accoutrements? I like how you include yourself here as an adorable soccer kid.

AC: Yes, so many plastic trophies. Soccer was my sport [laughter]. I’m an only child, so the photos in the background are all of me. The mantle is like this weird relic of my childhood accomplishments. While the figure isn’t particularly me, here it feels like a stand-in for my lived experience. It makes me think about all the time that has passed and how those photos and trophies have stayed right there this entire time.

LX: What got you interested in making figures in this way?

AC: I’ve always been interested in representing the figure, but it wasn't until a couple of years ago that I decided to represent how it feels to inhabit a human body, as opposed to how it’s perceived by others. The figures that I create sometimes appear dissociative and trapped, which relates to my interest in how our experiences and environment can impact our bodies and how we live in them.

LX: What does the doll signify for you?

AC: It’s not so definitive. I am still figuring out what it means to me and I think that will always change. Kind of like your relationship with anyone in your life. However, I do think that the doll is not a specific person but more of an idea. One of the things I am thinking about is the experience of navigating late-stage capitalism and the demands of what it takes to survive in that environment, as well as the effects it has on our body and our mind. I identify with that experience, but it is not me or anyone in particular.

LX: What’s the doll’s origin story within your practice?

AC: The original figure came from a small painting I made in the corner of my room in 2020. I ended up painting over it, so the original no longer exists, but I was referencing that image for a couple of years. I was really drawn to the disassociative eyes and full cheeks in the figure and those elements kept reappearing in my new works. One day, I was curious about what would happen if I made the figure three dimensional, so I cut the canvas into the shape of a doll stencil, sewed it, and stuffed it with reusable bags. I painted it and it sat on the floor of my studio for quite some time. I was struggling in my practice, so in order to get out of my own head I decided to make plaster and paper mache masks purely for fun. One morning in my studio, I got the idea to put one of the masks on the doll. That’s when the character really came to life.

LX: I like the sense of ennui or boredom. Are all of the figures self-aware?

One of the things I am thinking about is the experience of navigating late-stage capitalism and the demands of what it takes to survive in that environment, as well as the effects it has on our body and our mind.

AC: I think they are self-aware and they are searching for something, like we all do. As we lose our sense of community and become more isolated from one another it is easy to feel disconnected, lost and like you are operating on auto-pilot. Like, why am I even here? What is my purpose in life? That sense of nihilism is another theme I am investigating through the lens of the doll.

Figure 6: Amy Chasse, Night Swim, 2025, pencil and oil on canvas, 42 x 30 inches (106.68 x 76.2 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Amy Chasse

LX: Did you grow up in a religious household?

AC: Yes, I went to Catholic school until sixth grade. At one point, there were only going to be three kids in my grade, so they combined the fifth and sixth grades because they didn't have enough students.

LX: Wait, how many kids were in your school?

AC: Definitely under 100 in the whole school from kindergarten to eighth grade.

LX: Oh my God, how did you turn out to be so normal [laughs]?

AC: That's because I escaped to public school in sixth grade [laughter].

The figures that I create sometimes appear dissociative and trapped, which relates to my interest in how our experiences and environment can impact our bodies and how we live in them.

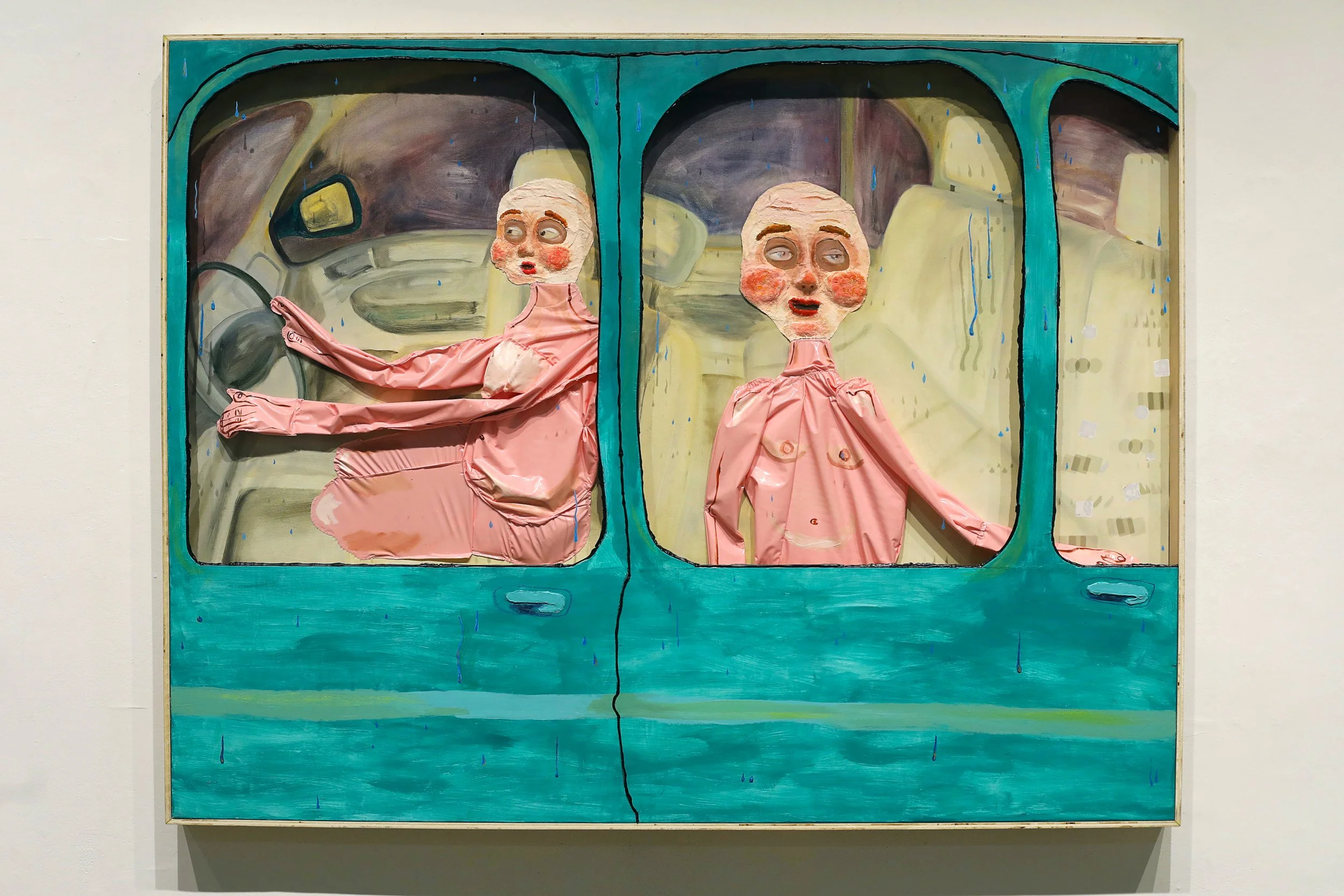

LX: Take me through the one with the car.

Figure 7.1: Amy Chasse, In Transit, 2025, oil, acrylic, oil pastel, plaster, stickers, silicone, vinyl and wood on canvas, 75 x 58 inches (190.5 x 147.32 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Amy Chasse

Figure 7.2: Amy Chasse, In Transit (detail), 2025, oil, acrylic, oil pastel, plaster, stickers, silicone, vinyl and wood on canvas, 75 x 58 inches (190.5 x 147.32 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Amy Chasse

AC: The idea for this piece came from the memory of being a kid in the backseat of my mom’s car, watching raindrops race down the window. I am interested in how something mundane can become animated through your imagination, especially in childhood. The piece started out as a painting and ended up becoming more sculptural, similar to a diorama. There’s three inches of wood framing the sides and the front piece is also made of wood. I cut out large organic shapes with a jigsaw and inlaid plexiglass to create car windows. The figures are actually physically trapped in between the canvas and the plexi.

LX: That’s really interesting. It reminds me a bit of something in Manet’s work. In Manet’s Modernism, Michael Fried coined the term “facingness” to describe how Manet renders the subject as “facing” outward toward the viewer and confrontationally acknowledging the viewer’s presence as a “beholder.” Manet’s subjects appear dissociative but not entirely disengaged. That ambiguity changes how the viewer experiences the work, and imbues the work with a sense of theatricality.

Your figures’ eyes almost look a little bit inebriated or intoxicated in a way….they’re so gargantuan they look almost startled. It captures the tense dynamics between a mother and daughter, and the anxieties that motherhood brings, as being in the literal “driver’s seat” of responsibility. I picked up on that tension here. What aspects of abjection interest you the most?

AC: What you said about Manet and the eyes really resonates, since affect is central to my work. Like I said, the figures do not have a fixed meaning, so the viewer’s emotional response is what matters most to me. I’m drawn to creating something that feels both familiar and unsettling, where you want to look, but it also feels uncomfortable. That tension between attraction and repulsion is something we often experience in life, and it fascinates me.

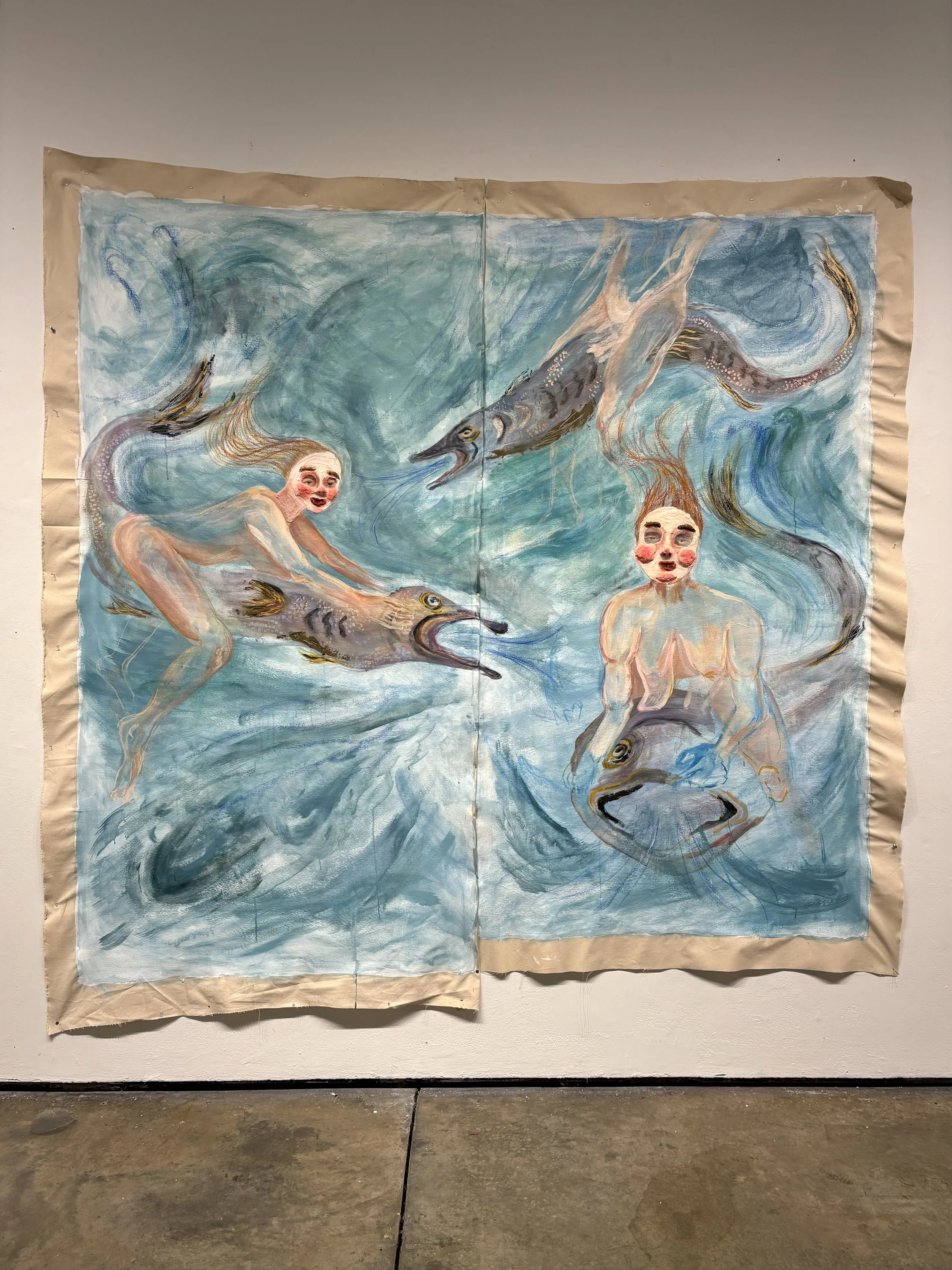

Figure 8: Amy Chasse, Riders, 2024, acrylic, plaster and paper mache on canvas, 85 x 75 inches (215.9 x 190.5 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Amy Chasse

LX: I love that. I also wanted to ask about this sprawling sea creature work.

AC: Before starting grad school I was working on a series of paintings with figures and fish. I started by looking at images of trout, which evolved into these eel hybrid sea creatures. A lot of my work has a fantasy element and water is a recurring theme, perhaps from spending time fishing with my dad as a kid.

LX: I’m also curious if you’re interested in queerness or performativity at all?

AC: I’m glad you caught that. Most people don’t. I’m queer, but I’m in a long-term heterosexual relationship, so people might not immediately assume that queerness informs my work. It definitely plays a role in the way I chose to render my figures, even if subconscious.

LX: Really cool. What’s your process like and which artists are you inspired by, if any?

Figure 9: Kati Horna. Untitled (Remedios Varo wearing a mask by Leonora Carrington), 1962, gelatin silver print, 8.5 × 7.75 inches (21.6 × 19.7 cm). Photo: courtesy the Kati Horna Estate © 2025 Kati Horna Estate, Carol and David Appel Family Fund, Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York, NY (966.2018)

I’m drawn to creating something that feels both familiar and unsettling, where you want to look, but it also feels uncomfortable. That tension between attraction and repulsion is something we often experience in life, and it fascinates me.

AC: I’m constantly influenced by things I see out in the world. I often make quick sketches of figures I find interesting even if I’m unsure why I’m drawn to them. I might love the cheeks in one sketch and then see a movie character with a fascinating nose, and I’ll stitch or collage it all together to make something new. These Frankenstein-like characters naturally find their way into my work.

As for artists, I'm really into her Cindy Sherman right now. I’ve also been drawn to the three witches of Surrealism: Remedios Varo, Leonora Carrington, and Kati Horna. Horna is less known, but her photographs, dolls, and masks really speak to me. There’s something uncanny and almost documentary that really draws me in. During critiques, I was continuously encouraged to watch David Lynch’s Twin Peaks and Eraserhead, so I’ve started exploring his work too.

LX: Can you tell me about what’s on your agenda for this road trip with your doll you’re about to embark on?

AC: Yes! I’m taking a 10 day road trip with the doll to explore what some people might consider to be “fly over states”.

LX: That’s epic [laughter].

AC: Yeah, I’ve always been drawn to the rural and suburban areas of the U.S. that are often perceived as mundane, but make up so much of the American landscape. My travel plans are flexible, so I can take local recommendations and pivot based on curiosity and intuition. I’m approaching the trip as a 10 day durational performance and want to investigate how my relationship with the doll evolves and changes over time. I plan to observe and document my vulnerability to the doll and the projections I put onto it. I like the notion that the doll has the potential to be my road trip partner, a stand-in, my only friend, an enemy, an annoyance and so much more. I’ll be using the time to reflect on the “illusion” of a roadtrip as a means of escape from things, to write, and to photograph our life journey together.

Amy Chasse

Amy Chasse (b. 1997, Norwich, CT) investigates the paradox of inhabiting a human body that is simultaneously present and absent of self. Through cutting, stitching, stuffing, and brushing, Chasse uses figuration to engage with the abject, creating emotionally and physically depleted figures or “dolls” that confront feelings of nihilism and otherness within the human condition. She films and photographs these dolls in domestic spaces she considers “psychic interiors,” examining the impact of late-stage capitalism on the nuclear family. Within these interiors, her figures serve as conduits between reality and an alternative world. Through interdisciplinary modes of making, she explores the intersections of transgression and desire. Chasse is based in Brooklyn, NY and is currently pursuing her MFA in Painting/Printmaking at Yale University.