To Burn, To Float, To Refuse: In Conversation with Joy Li

Whether crawling on all fours in durational performances or staging quiet rebellions in glass-walled offices, Joy Li’s work resists the familiar. With Lara Xenia, Li reflects on the evolution of her practice—from early sculptural experiments to her recent works with fire, transparency, and edible forms.

Lara Xenia: Tell me about your current series.

Figure 1.1: Joy Li, Transparent Trap, 2025, glass, butterfly specimen, screen,printed circuit board, rubber, 7.1 × 12.6 × 6.7 inches (18 × 32 × 17 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist, Podium Gallery, and Lok Hang Wu © Joy Li

Figure 2.1: Joy Li, Specimen Collection, 2025, 29.5 × 19.7 × 23.6 inches (75 × 50 × 60 cm), glass, banknote, metal, LED, ceramic, copper wire, and rubber. Photo: courtesy the artist, Podium Gallery, and Lok Hang Wu © Joy Li

Joy Li: My latest work, now on view in a solo exhibition at Podium Gallery in Hong Kong, explores transparency, both as a material and a concept. The title, Green Water, reflects the interplay between rational thought and emotion—two forces that often operate consciously and unconsciously at once. I think maintaining that balance is essential. The exhibition includes works that mark a shift in my practice. Last semester, I took a scientific glassblowing class in Yale’s chemistry department, where I learned to make lab-grade glassware…not for art, but for experiments. I had never worked with glass before and wasn’t sure how it would relate to my work.

In a group critique with Sarah Oppenheimer and the first year cohort, others described my work as mysterious and narrative-driven—terms I hadn’t associated with my practice. That moment pushed me to reconsider how I construct and expose meaning, both materially and conceptually. In these new pieces, both the exteriors and interiors are fully transparent. The wires and circuit boards I once concealed are now exposed. It was a major shift, but also incredibly freeing; the material clarity mirrored a conceptual breakthrough, and the sleek surfaces made my older, boxier pieces feel outdated.

Figure 2.2: Joy Li, Specimen Collection (detail), 2025, 29.5 × 19.7 × 23.6 inches (75 × 50 × 60 cm), glass, banknote, metal, LED, ceramic, copper wire, and rubber. Photo: courtesy the artist, Podium Gallery, and Lok Hang Wu © Joy Li

LX: It definitely has an industrial quality. Knowing you took a chemistry-based class makes it even more interesting because there’s almost a formulaic logic to it that I wouldn’t have initially picked up on. Even visually, it’s like a pipeline—with money on the front. It’s a compelling connection.

JL: I used to work a lot with butterfly wings in earlier pieces, but I wanted to go beyond the insect itself and explore butterflies as cultural symbols. In this work, I show various banknotes from around the world that feature butterflies. There are 123 in total.

Figure 1.2: Joy Li, Transparent Trap (detail), 2025, glass, butterfly specimen, screen,printed circuit board, rubber, 7.1 × 12.6 × 6.7 inches (18 × 32 × 17 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist, Podium Gallery, and Lok Hang Wu © Joy Li

LX: Fascinating. What do papillons mean for you, then?

JL: I see butterflies as representations of the human body, with its fragility, both physical and mental, in contemporary settings. The structures are inspired by architecture. Inside, I placed a slow-motion video of a blooming flower, which I think of as an advertisement for butterflies.

LX: I love how participatory that piece is. Have you explored interactivity in other works as well?

JL: Yes, in my solo exhibition in Shanghai I made an edible cookie sculpture that people could eat during the opening. I wanted people to be able to digest and absorb my sculptures, until the sculpture disappeared. I was struggling with all the storage and shipping, so I thought it was a perfect solution [laughter].

Figure 3.1: Joy Li, Ouroboros, 2023, 2.17 × 2.17 inches (5.5 × 5.5 cm), cookie. Photo: courtesy the artist © Joy Li

Figure 3.2: Joy Li, Ouroboros, 2023, 2.17 × 2.17 inches (5.5 × 5.5 cm), cookie. Photo: courtesy the artist © Joy Li

LX: How fun. How many cookies did you make? The food component vaguely reminds me of Rirkrit Tiravanija’s Pad Thai Diplomacy performance.

JL: Yes, yes, definitely. I think I probably made 60 or something. They were all gone.

LX: They look delectable, so I bet. What are you currently researching?

JL: I’m researching miniature theme parks in China, specifically The Window of the World in Shenzhen, where I’m currently based. It was built in 1994 and features around 100 scaled-down global landmarks, from the Pyramids to the Eiffel Tower. I’m interested in moving beyond critiques of Western imitation to explore why it was built when it was—maybe to signal China’s recovery, modernization, and global integration. There’s a kind of pride in it: you don’t need to leave China to see the world—the world is already here. I’m in early talks with a curator friend who specializes in East Asian architecture about a potential collaboration, and I’m still reading to find my entry point. I’m optimistic that it could become my thesis.

Figure 4: China Travel Service (Holdings), Hong Kong Limited and OCT Group, New York Cityscape at The Window of the World, Shenzhen, China, 1994

This is a miniature of New York City, with the Twin Towers. It was the first park I ever visited as a kid, and after revisiting it last week, it felt completely outdated, now that the vicinity is surrounded by sleek skyscrapers. My recent works are directly influenced by architectural models. They carry layered meanings—a hopeful vision of the future, a sense of panoramic control, and the playfulness of a manipulable toy. I’m still exploring what that ambiguity means for my practice.

LX: Speaking of your practice, I was really moved by your multichannel work and intrigued by your use of an antenna in the video I saw in your studio. Could you walk me through how that piece came together?

JL: I began developing that body of work three years ago, exploring performance, sculpture, and installation. I gradually became interested in how to use footage and documentation from my performances more creatively. I see all of my works as part of an ongoing study of the same themes. I started thinking about how to construct a narrative through this documentation—whether through a vlog or a self-documentary video that not only shows the performances, but also reveals the intentions behind them. My first video work was my undergraduate thesis, The Deviation of Desire. It features a projection of my hand interacting with my own body as I perform a series of actions involving fire, and I later compiled the footage into a single, cohesive video.

Figure 5: Joy Li, The Deviation of Desire, 2021, single-channel video, color, sound, 13 minutes 39 seconds, https://vimeo.com/540782835

Since then, I’ve created more video works while also considering their sculptural qualities. As a sculptor, I’m interested in giving video works a tangible presence—something the audience can physically navigate and experience with their whole body. The work you saw in my studio was my first attempt to integrate everything from live performance, installation, and multichannel videos. That marked a turning point.

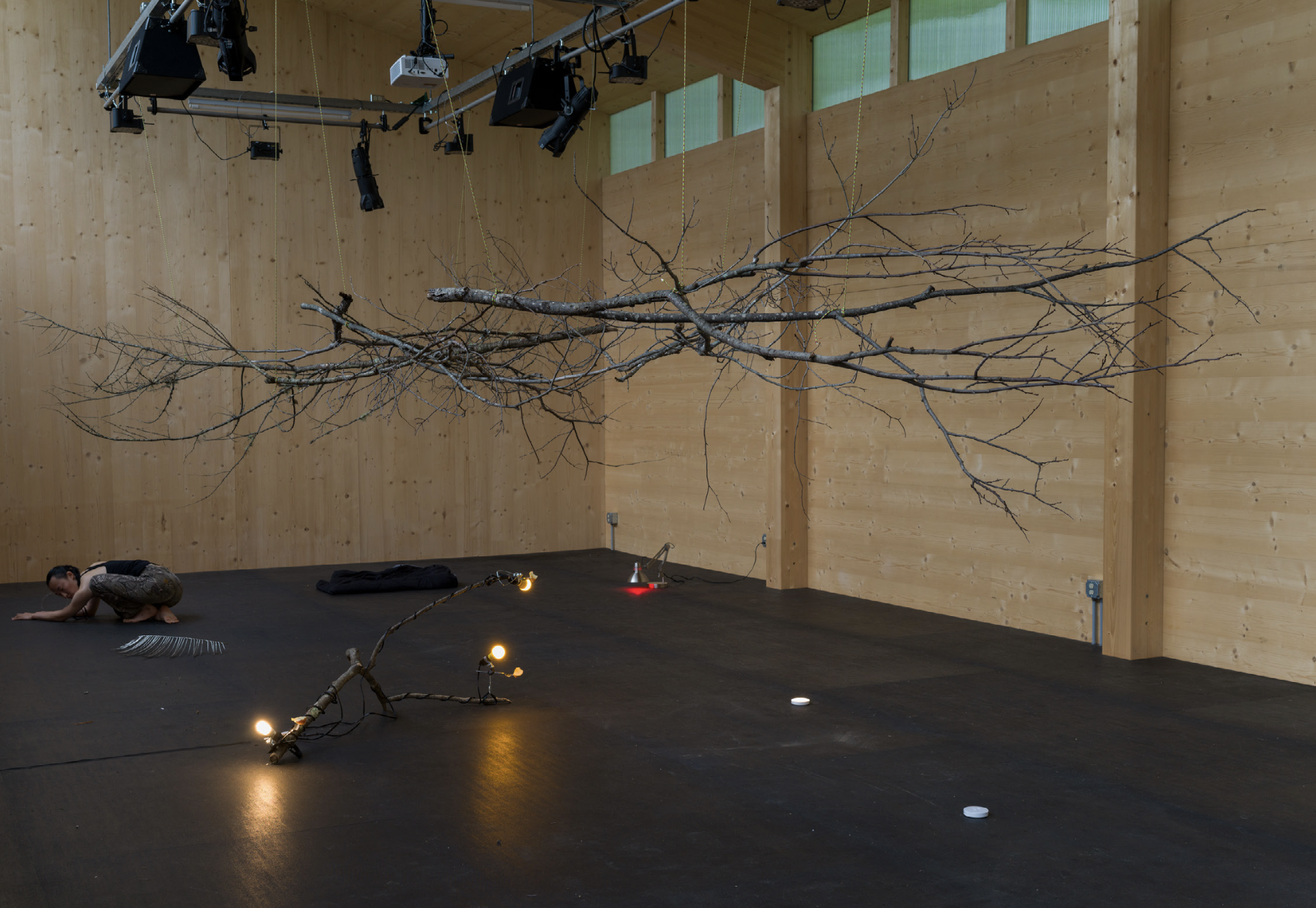

Figure 6.1: Joy Li, Intermission, 2024, performance. Photo: courtesy the artist and Maximiliano Cervantes © Joy Li

Figure 6.2: Joy Li, Intermission, 2024, performance. Photo: courtesy the artist and Maximiliano Cervantes © Joy Li

Before starting at Yale, I attended the Skowhegan Residency, where I created Intermission. I transformed my body into a nonhuman, monster-like figure using white contact lenses that blocked my vision, allowing me to see only colored lights. Intermission was also my first durational nonhuman performance. For five hours, I actively moved through the space and interacted with a live audience. After the audience left, I spent the night in the performance space, and it wasn’t until I woke up the next morning and walked out that the performance truly came to an end.

LX: That’s wild to me. That must’ve been exhausting.

JL: Yes. That performance really pushed me to think about the limits of the human body. It’s essentially impossible to become truly nonhuman—our behaviors are deeply tied to our physical form, especially our ability to walk upright. In that piece, I was on all fours, which is a recurring gesture in my work. Crawling disrupts the body's usual movement—it’s one of the fastest ways to shift into something unfamiliar or unsettling. The experience raised a larger question for me: is becoming nonhuman even possible, or is it an inherently futile pursuit? That question inspired the development of my video installation and performance work.

Figure 6.3: Joy Li, Intermission, video installation, 2025, 20 minutes 56 seconds, https://vimeo.com/1061913339 © Joy Li

LX: I was especially struck by the physicality of your performance and the way you integrated microeconomics into the premise.

JL: Yes, during my first semester at Yale, I took a microeconomics class because I was curious about how people make decisions. Microeconomics is really about allocating limited resources. I started thinking of those resources not just as money, but as time and energy, especially in performances. Models like opportunity cost and diminishing returns became useful frameworks to reflect on what I put into each performance versus what comes out of it.

The experience raised a larger question for me: is becoming nonhuman even possible, or is it an inherently futile pursuit?

In that video sculpture, I brought together elements of performance, economics, and sculpture. The piece plays with the sculptural notion of front, side, and back: the front consists entirely of screens, while the back features a small window revealing a piece of paper perforated with the word “Now”—a reference to the present moment. I also placed a treadmill on top, using it as an instrument by pressing my fingers and hands against it to generate sound.

LX: I liked how introspective you were when you spoke about your life experiences. I also vividly remember the scene of you walking nude in the middle of a road in Maine, and the Shenzhen city slogan on your studio wall still cracks me up [laughs].

Figure 7: “Time is Money, Efficiency is Life”, Shenzhen, China. Photo: Wikipedia Commons

JL: Yes—that slogan is from my hometown, Shenzhen [laughs]. I find it fascinating, especially in how it reflects the ways bodies and minds are shaped by their environments. I’m particularly drawn to themes of desire, fear, and anxiety, and “Time is Money, Efficiency is Life” reflects a key component of what drives my work.

LX: I have to ask: do you ever feel vulnerable when you perform in the nude?

JL: When I’m performing, I don’t really think about it. I consider how people might react before or after, especially when reviewing the documentation…but once I’m in it, I’ve already made the decision. I know what I want to do, and I just commit to executing it.

LX: I wish I could do that, and I have a lot of reverence for the way you perform—it’s such a brave thing. Being proud and comfortable in your body is powerful, and I think that’s what makes your performances so captivating. As an audience member, you can really feel that you’re fully present, as both yourself and the performer.

I’m particularly drawn to themes of desire, fear, and anxiety, and “Time is Money, Efficiency is Life” reflects a key component of what drives my work.

JL: It’s funny because you said I seemed really present, and I was, but I also felt detached from my body. At that moment, it became artistic material. The discomfort or shame we feel about exposing ourselves comes from cultural norms, but during the performance, I set that aside. I’m not Joy Li the person—I’m part of the work. I don’t think about it until afterward, when I return to being a social being and go, “Oh god, that’s how I looked? Okay…fine.” [Laughter]

LX: What does performing mean to you?

JL: Performance, for me, is about surrendering—on my own terms. It’s never just chaos. I build a structure, like my tent, and within that, I allow myself to lose control. That in itself is a form of control.

LX: That’s beautiful. Let’s look at some of your older works together.

I’m not Joy Li the person—I’m part of the work.

JL: Yes, yes. [Points to portfolio] This is a bow tie. We usually use them for luxury packaging. In Chinese, we call them “butterfly knots”, so I decided to render an artificial butterfly killing a bunch of real butterflies in this sculpture.

LX: This slit looks like a snake's tongue.

JL: Yes, that’s deliberate.

Figure 8.1: Joy Li, Butterfly Killer No. 01, 2024, 39.37 × 39.37 × 43.31 inches (100 × 100 × 110 cm), stainless steel, butterfly specimens, resin, ceramic tiles, epoxy, and acrylic. Photo: courtesy the artist © Joy Li

Figure 8.2: Joy Li, Butterfly Killer No. 01 (detail), 2024, 39.37 × 39.37 × 43.31 inches (100 × 100 × 110 cm), stainless steel, butterfly specimens, resin, ceramic tiles, epoxy, and acrylic. Photo: courtesy the artist © Joy Li

I build a structure, like my tent, and within that, I allow myself to lose control. That in itself is a form of control.

LX: I’m enamored by this work where you’re suspended in the air. It looks like a magic trick!

Figure 9.1: Joy Li, Wings of Icarus, 2024, iron, wax, paint, nylon rope, cotton thread, and human body. Photo: courtesy the artist © Joy Li

Figure 9.2: Joy Li, Wings of Icarus, 2024, iron, wax, paint, nylon rope, cotton thread, and human body. Photo: courtesy the artist © Joy Li

Figure 9.3: Joy Li, Wings of Icarus, 2024, iron, wax, paint, nylon rope, cotton thread, and human body. Photo: courtesy the artist © Joy Li

JL: For Wings of Icarus, I was sitting on something that supports my body. I was inspired by how street performers have props that can make them actually appear as if they’re floating. I made this installation that could make me float in the middle of the air, but it's also an illusion, with a big city backdrop.

Fire is a source that requires energy. While the candle burns and drips on my hands and the skeleton in my wings, wearing white contact lenses made me completely blind, except for being able to see the light of the flames. The flames appeared in my vision as flickering red triangles. At that moment, I felt connected to Icarus and I began to meditate on why Icarus could not resist the temptation of the Sun. Let me read you the accompanying poem I wrote for it:

With the wings that I constructed from features and wax, I flew to the Sun, My gaze made you overly beautiful, Like a giant incandescent egg of an idol. I approached with sanity, knowing the cost of your lethality I was aware of the importance of distance, And I thought I was in control Until defeated by my cowardice.

Wings caught fire, eyes were burnt, but blindness has brought the true vision. When my life was on the line, the blindness helped me escape from my body and return to infinity.

Time disappears. The falling suspends And now, I know what to do.

I should shut up.

That was the first time I used those white contacts in my work, which definitely influenced Intermission. I made the skirt specifically for that piece. The illusion I was aiming for was one of weightlessness—of floating—but in reality, I couldn’t move. It’s about the tension between the desire for freedom and the constraints of life in a modern city.

LX: Wow. The only other figurative candle-based sculptures I’ve seen are Urs Fischer’s ephemeral melting works—but I’ve never seen someone hold fire in a gallery space.

Wings caught fire, eyes were burnt, but blindness has brought the true vision. When my life was on the line, the blindness helped me escape from my body and return to infinity.

Figure 10: Urs Fischer, Untitled (after The Abduction of the Sabine Women by Giambologna), 2011–2020. Photo: courtesy the artist, the Pinault Collection, and Stefan Altenburger © Urs Fischer

In your poem, you write about blindness as a condition that allows you to exist. Was there a specific moment that drew you to performance, where you felt, “This will set me free”? And did that moment also spark your interest in exploring themes of blindness and light?

Figure 11.1: Joy Li, This Performance is a Form of Refusal, 2021, metal, fabric, faux fur, hair, cable tie, feather, and human body. Photo: courtesy the artist © Joy Li

Figure 11.2: Joy Li, This Performance is a Form of Refusal, 2021, metal, fabric, faux fur, hair, cable tie, feather, and human body. Photo: courtesy the artist © Joy Li

JL: Yes, this piece felt connected to an earlier work I made in 2021 called This Performance is a Form of Refusal. After graduating in the middle of COVID, I moved back to China and settled in Shanghai. Although I had studied sculpture in undergrad, I initially took a job as a graphic designer for this luxurious shopping mall on the underground floor. It was windowless and drenched in cold, white light. The office culture felt deeply performative, and built on a hierarchy of flattery and suppression.

I remember thinking, “If being human means this, I’d rather be something else.” My second job was in branding design, mainly for restaurants and similar clients. The office was located in a sleek skyscraper—polished, regulated, and deeply alienating. And I was still haunted by a simple thought: “I’d rather be something else.” So I started to make body extensions, like wearable sculptures, and apparatuses, to transform myself into something “other”, something monstrous. Two days before I quit, I even snuck into the office at night, staging a kind of quiet rebellion and protest.

LX: That is so iconic and has such Charles Bukowski-energy. You were probably on all of the security cameras [laughter].

JL: I know, right? I’d pay to get that footage. I was there around 2:00 or 3:00 A.M., walking through the space in that outfit. I went into the meeting room where we used to gather, then into my office where I sat for eight hours a day. Looking back, I realize a lot of my performances are small acts of protest in one way or another.

Figure 12.1: Joy Li, Rattlesnake, 2024, 3D printed resin, wood, sponge, springs, bells, metal, fabric, crystal chandelier, pendants, hair, essential oils, fishing line, and human body. Photo: courtesy the artist and Liang Zilong © Joy Li

Figure 12.2: Joy Li, Rattlesnake, 2024, 3D printed resin, wood, sponge, springs, bells, metal, fabric, crystal chandelier, pendants, hair, essential oils, fishing line, and human body. Photo: courtesy the artist and Liang Zilong © Joy Li

Figure 12.3: Joy Li, Rattlesnake, 2024, 3D printed resin, wood, sponge, springs, bells, metal, fabric, crystal chandelier, pendants, hair, essential oils, fishing line, and human body. Photo: courtesy the artist and Liang Zilong © Joy Li

LX: I love that for you. On a more personal note, do you ever feel pressure to censor yourself or resist being labeled as a “Chinese artist”?

JL: Definitely. I don’t deliberately frame my work through identity, but those layers of being Chinese and being a woman are inseparable from how it’s perceived. I’ve moved a lot, both within China and to the U.S., and that nomadic experience, along with navigating censorship, taught me you can’t control interpretation. There’s no perfect place to live or make art; it’s about knowing what matters to you and adapting. For me, being smart and nimble is key.

LX: Thank you for sharing your insights on that with me. Which artists or figures do you look up to?

JL: As a kid, I admired Snoopy for his carefree spirit—he did whatever he wanted, whether he was a pilot or a writer, without worrying about others’ opinions [laughs]. But in terms of artists, I really like Rebecca Horn and Pierre Huyghe; he is probably one of my favorites. I also like Martha Barney, Annicka Yi, and Hiro Stora.

LX: Lastly: what do you hope your performances leave behind?

JL: I want the audience to re-experience and reflect on the familiar—the body, and the desires, power structures, and mundane routines that unfold around it. Within these everyday encounters, can we discover new possibilities?

Joy Li

Joy Li (b. 1999, Gansu, China) obtained her BFA degree in Interdisciplinary Sculpture with a Theater minor at the Maryland Institute College of Art in 2021. She is currently studying in the MFA Sculpture program at the Yale School of Art, and is expected to graduate in 2026. Her works include sculpture, installation, performance, and video, exploring the tension of interactions between objects, emotions, and relationships. In her works, she reinterprets objects and bodies to magnify the allure and danger inherent in everyday items, allowing the audience to re-experience and interact with familiar things in unfamiliar ways.

She is the recipient of the 2025 Schickle-Collingwood Prize from the Yale School of Art and the 2024–2025 Porsche “Young Chinese Artist of the Year” Award. In 2024, she also attended the Skowhegan School of Painting & Sculpture.

Her recent solo exhibitions and projects include: “Gas Station X”, 2024, Vanguard Gallery, Shanghai; “Icarus’ Wings”, 2024, Guangdong Times Museum, Guangzhou; “Green Water”, 2023, LINSEED, Shanghai; “Golden Lines and White Lightings”, 2023, Aranya, Chengde; “Salomé”, 2022, 33ml OFFSPACE, Shanghai. Her selected group exhibitions include: “Ballet with the Devil”, PODIUM, Hong Kong; “Porsche ‘Young Chinese Artist of the Year’ Nominees’ Exhibition”, Shanghai Exhibition Center, Shanghai; “Four Winds: A Different Perspective on Southern Art”, 2024, Guangdong Contemporary Art Center, Guangzhou; “Open the Door”, 2024, Gallery func, Shanghai; “At the Beginning, You Find Nothing There”, 2024, Petitree, Shenzhen; “Embodied Rituals”, 2024, Guangdong Times Museum, Guangzhou; “After Human: Marks of the Beasts”, 2024, Tomorrow Maybe, Hong Kong;“moments that home came into being”, 2023, Third Street Gallery, Shanghai; “Tie Up”, 2023, Mugyewon, LINSEED, Seoul; “LAB 2: Co-Working Space”, 2022, LIU HAISU Art Museum, Shanghai; and “Art Nova 100”, 2021, Guardian Art Center, Beijing.