Billionaire Birthdays and Optic Time: In Conversation with Garrett Ball and Kevin Cobb

Lara Xenia speaks with longtime friends and artists Kevin Cobb and Garrett Ball about their shared interests in Escher, architecture, religion, and drawing.

Figure 1: Garrett Ball, 1000 5th Ave, 2024 watercolor on paper, 46 x 34 inches (116.84 x 86.36 cm), 2024; framed 56 x 34.5 inches (142.24 x 87.63 cm).

Garrett Ball: I’m going to say my favorite quote again, so you both remember this time: a million seconds is 12 days, and a billion seconds is 31-and-a-half years. By 31, you might be closer to a billionaire birthday than you realize. I’ll have a lot of my friends type in their birthdays and ask, “What will the date be 11,574 days from the date of my birth?” That’s your billionaire birthday, where you turn a billion seconds old. I've been encouraging all of my friends to celebrate [laughter].

Kevin Cobb: A billion seconds old? [Laughs]

GB: I mean, what else are you ever going to be a billionaire in? I’ll probably never be a billionaire in anything except seconds…and maybe breaths, but I don’t breathe every second. It feels way bigger than a birthday because you only get maybe three of these in your life, if you’re lucky. I made all the Columbia kids come out and celebrate mine [laughter].

Lara Xenia: I can totally envision you throwing a fête for that, Garrett. I remember that you both share a love for M.C. Escher and playing with perspective. What was your first experience of seeing his work?

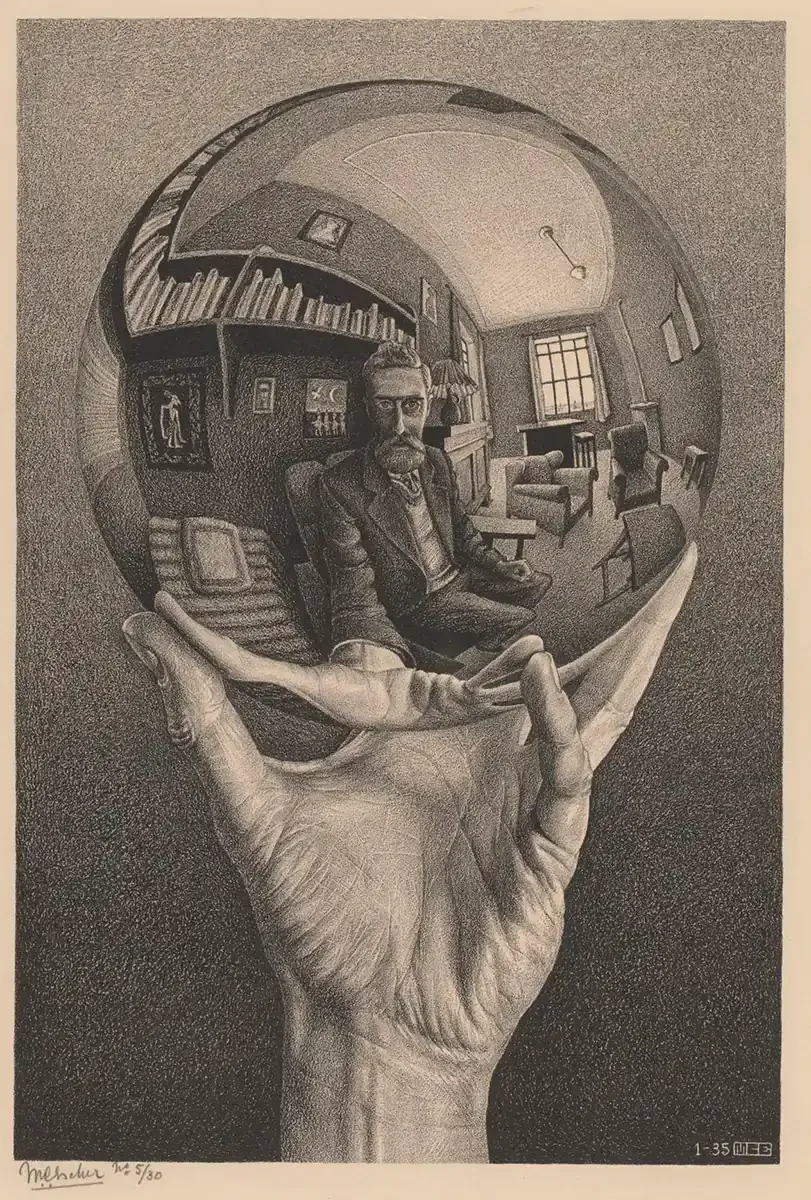

Figure 2: M.C. Escher, Hand with Reflecting Sphere (Self-Portrait in Spherical Mirror), January 1935, lithograph, 12.51 × 8.39 inches (31.8 × 21.3 cm). Courtesy Escher in Het Paleis, Hague, NL

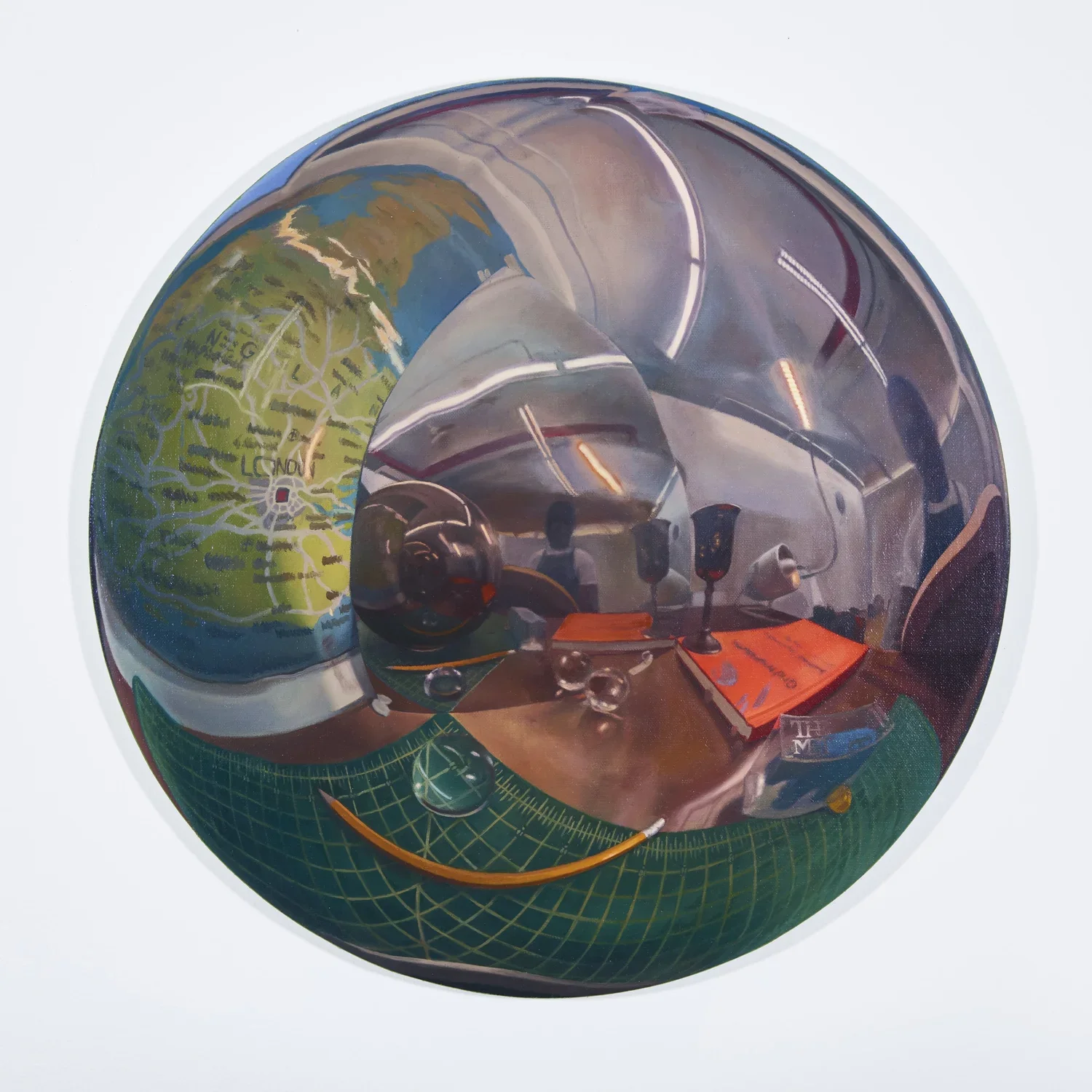

Figure 3: Kevin Cobb, The Macrowave, 2023, oil on linen, 20 x 20 inches (50.8 x 50.8 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Kevin Cobb

Figure 4: Kevin Cobb, Orbicular Blurse, 2022, oil on canvas, 20 x 20 inches (50.8 x 50.8 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Kevin Cobb

KC: I first encountered Escher’s work in high school at the George Washington Carver Center for Arts and Technology in Maryland. We had access to a lot of art books that really stuck with me like Escher, Neo Rauch, Claudio Bravo, and other Realist and Surrealist artists, so I've loved him ever since. His art may have fallen out of favor a bit, but it still resonates. I used to play video games as a kid that let you navigate impossible puzzles, with weird 2D and 3D spaces like the ones he explored in his work.

GB: Yeah, it’s hard to pinpoint, because Escher is so ubiquitous…he’s ingrained in the culture. His impossible shapes and buildings, mirror spheres, and morphing animal patterns are images that pervaded my childhood. He was one of my first access points into art before “art” with a capital A. Then you’re expected to grow out of it, you get to art school, and suddenly he isn’t “cool” anymore. I always scoffed like, “Wait, growing up, this guy was the man! What do you mean we’re above him now?” [laughter]

LX: True; I remember his work being in math classrooms and later reading Gödel Escher Bach. What got you interested in making spherical self-portraits, Kevin?

KC: Initially from painting Christmas ornaments. I made some alright ones in high school, and then I learned about Escher and the Mannerists, which made me consider the warping spaces and figures more deeply. Recently, I made an artwork inspired by the giant, NYC mirror ball by Anish Kapoor. I was thinking about how a spherical mirror organizes space and how depicting figures in a warped space flattens and merges with the environment. That became my strategy for turning the figure into a formal language and integrating it more musically into the composition.

Figure 5: Kevin Cobb, Rainbow Pumpkin, 2017, oil on canvas, 50 x 44 inches (127 x 111.76 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Kevin Cobb

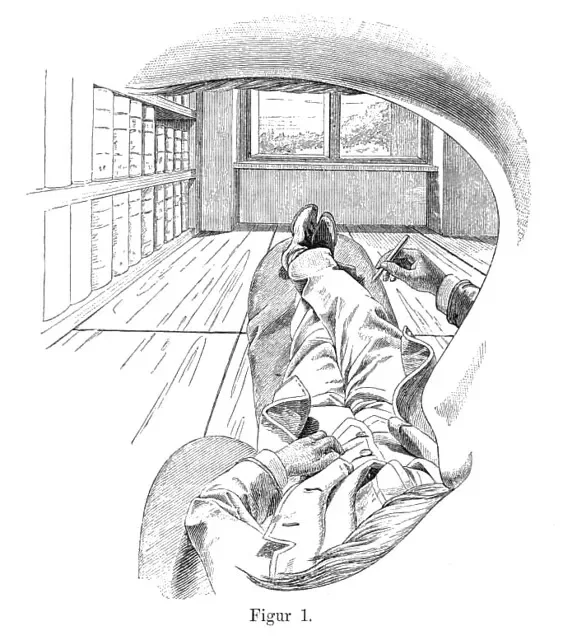

I then extended that to interiors. In this work, I used a convex mirror to simulate my perspective within a rectangular canvas, and vignetted it with black triangular borders to show my peripheral vision. You can see the outline of my nose in those brown overlapping lines. Since I’m painting the space entirely observationally, the black is the limit of what I can't see. When sketching it, I often use the markers of my face as a reference for modeling, and incorporate it into the scene. Painting on circular canvases allows me to think less about the painting as a window into a scene and more like a self-contained object.

Figure 6: Kevin Cobb, Spatium Interiorem, 2025, oil on tondo canvas, 60 inches (152.4 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Kevin Cobb

LX: Wow, it looks like a vortex. The eye one is also cool because your body is the “pupil.” What have you learned about yourself through doing this close observation?

KC: I was meditating a lot, and thinking about perception and spirituality. By including myself as one of the subjects, I’m considering what it means to be the observer within the body. In this work, I’m looking from the view of the retina within my right eyeball.

LX: You’re practically depicting “the hand of the artist” by painting yourself making the work.

KC: Exactly. I like painting from my own perspective by including my brow, my arm, or whatever I can see of myself, even without self-portraying reflections in space.

LX: That’s awesome. Could you tell me more about International Geometric: Hyde Park?

Figure 7: Kevin Cobb, International Geometric: Hyde Park, 2024, oil on linen, 18 x 18 inches (45.72 x 45.72 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Kevin Cobb

KC: That comes from when I lived in London for three years, and my interest in cartography. I had this map and a grid-systems graphic design book by Josef Müller-Brockmann. I was interested in signifying space geometrically, so I decided to paint it from the reflection of a mirror ball against a flat mirror to scatter the viewpoint and create recursion and depth. I like alluding to infinite space within a flat surface to contain a reflection of the whole.

GB: I love how Kevin’s oeuvre makes you aware of selective processing. You’re always seeing your nose, but your brain edits it out because it doesn’t register as important. It’s a clear example of how consciousness filters and defines perception. We’re constantly inundated with information, and there has to be an internal observer deciding what matters and how to respond. We both share this desire to break out of restrictions when creating an image or a space.

The rectangle can feel limiting since it traditionally keeps everything inside a box. Kevin and I are both interested in finding ways to show a bigger view, like something larger than what you can process in a single moment. I’ve been thinking a lot about how there are always multiple ways of looking at any subject or issue. You can probably see that more clearly in some of the pieces Kevin has there [points].

LX: No, totally. And it’s interesting that your entry point of depicting space is through drawing major institutions. What draws you to architecture?

By including myself as one of the subjects, I’m considering what it means to be the observer within the body. —KC

Figure 8: Garrett Ball, Terminal, 2023, watercolor and gold leaf on paper, 54 x 32 inches (137.16 x 81.28 cm); framed 56 x 34.5 inches (142.24 x 87.63 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Garrett Ball

GB: I use architecture as metaphors, since massive institutions that seem permanent and imposing are actually human-made and open to change. By depicting these rigid structures as malleable and adaptable, I suggest the same is true of the ideas and systems they represent. Institutions like the New York Public Library, the Metro North, the MTA, and universities can be reshaped to meet public needs. That’s really the core idea. Historically, despite their flaws, wealthy figures like Andrew Carnegie, Cornelius Vanderbilt, and J.P. Morgan felt some responsibility to invest in public culture through libraries, theaters, and educational institutions.

Those investments were meant to uplift society as a whole, but today, that sense of cultural responsibility feels diminished. So my work is a call to care for shared spaces to believe in society, and to use institutions to improve our collective environment, not just to accept them as fixed or untouchable.

Figure 9: Kevin Cobb, Cloudbound, 2024, oil on tondo panel, 20 inch (50.8 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Kevin Cobb

LX: That’s a fascinating take. I remember you made the Manifestation of the Hyperobject Prints from four panels of linoleum that could rotate in any direction in 280 different variations, as your way of trying to depict the exponential. How do you work with geometric shapes to make spatial continuums and could you tell us about your interest in superpositionality?

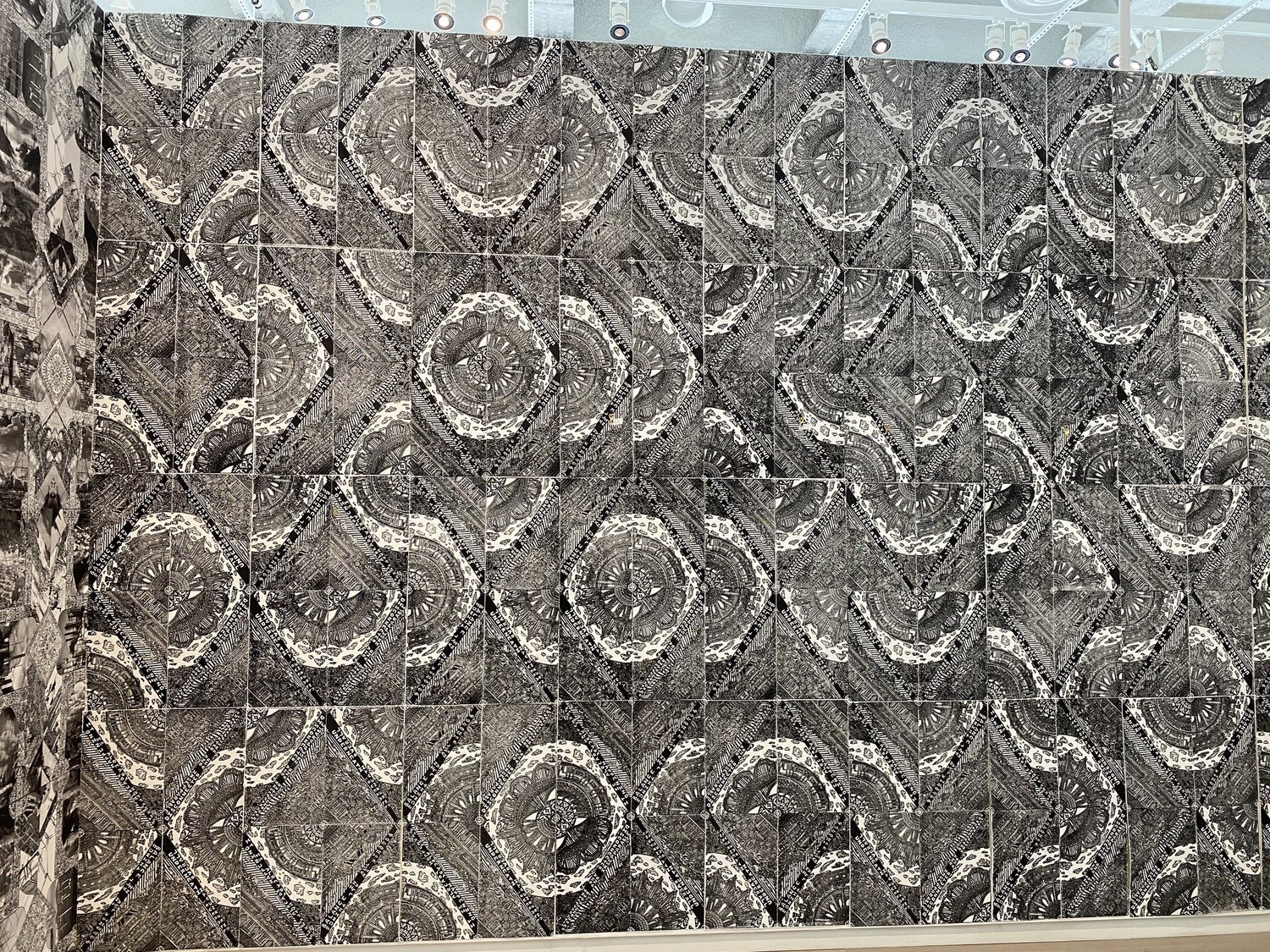

Figure 10: Garrett Ball, Manifestation of a Hyperobject, 2023, linoleum relief print on paper, 36 x 24 inches (91.44 x 60.96 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Garrett Ball

Figure 11: Garrett Ball, Manifestation of a Hyperobject, 2023, linoleum relief print on paper, 40 x 36 x 24 inches (101.6 x 91.44 x 60.96 cm) tiled, 20 x 12 feet total. Photo: courtesy the artist © Garrett Ball

GB: Yes, one challenge I’ve been working through is exploring how to bend or warp space in ways that aren’t true to the physical environment, but to create a continuous view or a perspective that isn’t broken by the limits of rectangular architecture. I love how you can unfold space with circles. Superpositionality refers to the way the modern world rarely allows you to exist in just one space or one time. As you move through your day, you’re thinking about your past, planning for the future, or maybe talking on the phone with someone a hundred miles away, all while trying to manage your own schedule. At the same time, you’re aware of world affairs and expected to take responsibility for your own history. We experience it more acutely now because of the digital age. We can only exist in our own moment, yet we’re constantly pulled into others. This layering of times, places and perspectives is something we have to learn to reconcile and find comfort within.

How do we operate as individuals when we’re asked to be mindful of so many different realities, responsibilities, and forms of interconnectedness? Where does it leave us? That’s part of why I’ve been making these pieces with views from the top, bottom, and all around. It’s a question I keep asking myself, like, “how do I exist within a space that’s larger than my own?”

LX: How do you determine which space you’d like to depict? Does the luminosity or atmosphere trigger something for you?

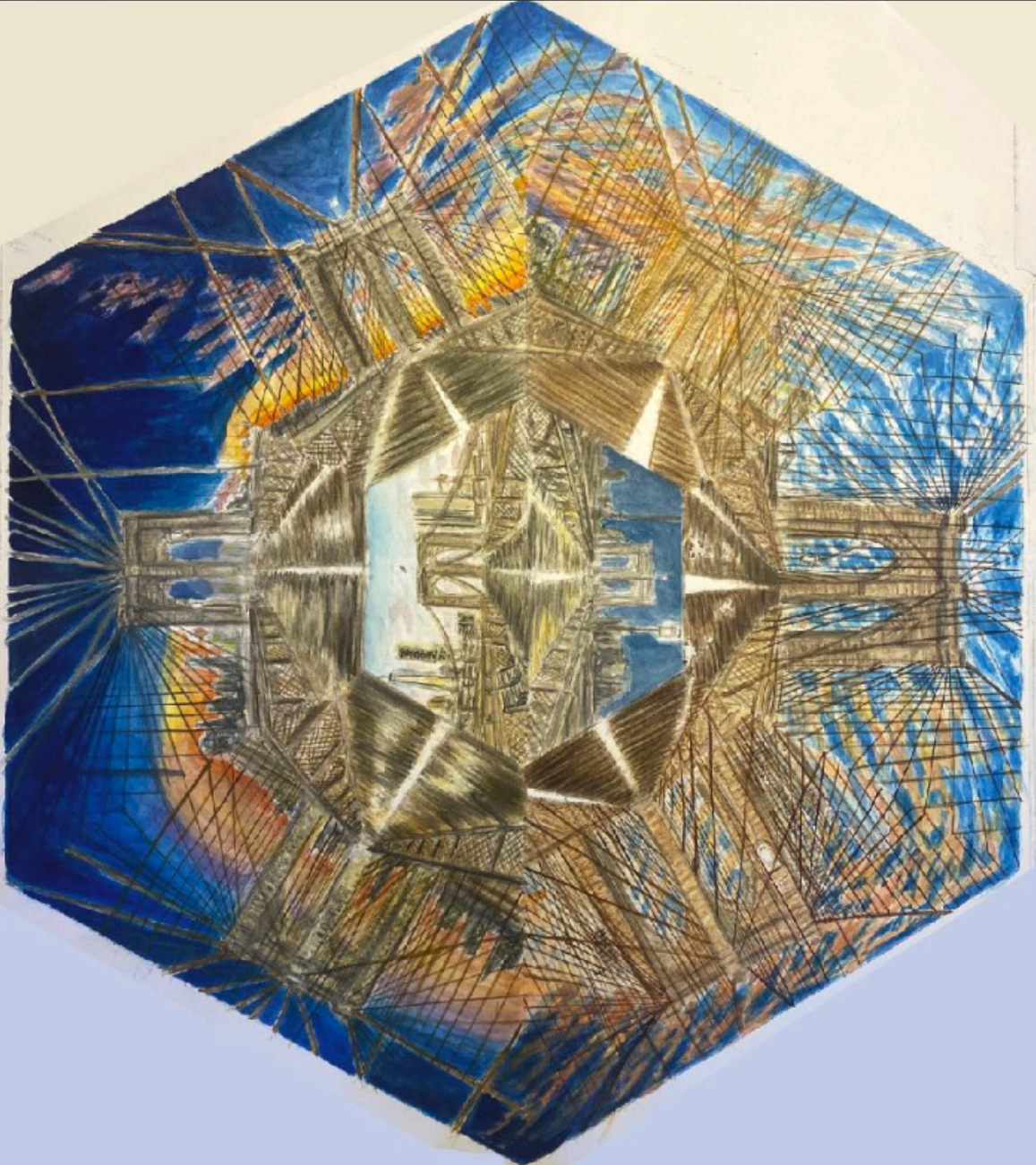

Figure 12: Garrett Ball, Brooklyn Bridge, 2025, watercolor on paper, 24 x 18 inches (60.96 x 45.72 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Garrett Ball

How do I exist within a space that’s larger than my own? —GB

GB: I’m really interested in public infrastructure because it creates a foundation for cultural conversations. We have a history and a culture we’ve built together, and part of our work is to care for and evolve it. I’m drawn to public infrastructure because it’s both physical and symbolic as like a metaphor for how we function collectively. Bridges, museums, and other civic spaces represent cooperation and shared responsibility to some extent, since the maintenance of those systems is what lets us move forward. So when I focus on cultural institutions, it’s not just for their beauty or architecture. It’s because they hold the tensions and questions I’m interested in…like how we sustain, adapt, and imagine together within the structures we’ve already built.

Bridges, like the Brooklyn Bridge piece, are indicative of some ideas I've been thinking about. Here, it’s set at the middle of the bridge, looking back from either side of that central point in this liminal space where you can only understand where you are by recognizing where you're not. As you go around the hexagon, the view shifts back and forth between the Manhattan and Brooklyn sides. You only know you’re in Brooklyn because you’re looking at Manhattan and vice versa. It’s this idea of orientation through absence, and of finding your place in relation to what you’re not. For a long time, I was making these highly political works that were didactic and informative and that used text linking them to a specific issue, lately I have been finding that a less heavy handed approach leads to a more productive dialogue.

[Cultural institutions] hold the tensions and questions I’m interested in…like how we sustain, adapt, and imagine together within the structures we’ve already built. —GB

LX: Some of your work feels almost mandala-like because it’s so meditative, and to your point, it makes me reflect on my relationship with sociopolitical structures.

GB: Yes, ultimately I want to make contemplative spaces that a viewer can perceive themselves in, and to give them a moment to sit with these ideas and process them. Modern culture doesn't give us a lot of time to reflect. You can see that in the watercolor about the Rose Reading Room at the New York Public Library. The ceiling there has these three panels that span the space, and I’ve repeated that pattern so the three appear in all sections. It gives you a view from every angle, as if the space is unfolding, like Gilders’ treasure boxes.

Figure 13: Garrett Ball, New York Public Library Rose Reading Room, 476 5th Ave, 2025, watercolor on paper, 44 x 33 inches (111.76 x 83.82 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Garrett Ball

KC: It’s interesting how they’ve started to look like finely cut diamonds or gems.

GB: No, definitely [shows sketches of new works]. I’ve been working on a drawing of the New York Surrogate’s Court expanded upon itself and another one of the dome of City Hall with the view reversed. You look up from the first floor and down from the third, which creates a helical perspective. I’m also drawing the Fulton Center near the World Trade Center to explore a more modern space, since some of the others started to feel too historic. I have another piece in progress at the Museum at Eldridge Street. It’s an incredible former synagogue on the Lower East Side that’s now a museum that you’ve gotta visit. I'm really interested in how we depict the divine and supernatural, or what is larger than ourselves.

Figure 14: Garrett Ball, St. Patrick's Study #2, 2025, watercolor on paper, 22 x 18 inches (55.88 x 45.72 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Garrett Ball

Figure 15: Garrett Ball, St. John the divine study 1, 2024, watercolor on paper, 18 x 22 inches (55.88 x 45.72 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Garrett Ball

LX: Do you ever lose yourselves while you're both making these?

KC: Only for certain pieces, but not the more representational ones. It depends on the work and its composition. For very abstract pieces, I try to hold on to what ties it together to give it the feeling I’m looking for, and get lost in the design and narrative behind it.

GB: I’d be really disappointed if I stopped getting lost in my own work. I want my paintings to have replayability, and to take time to absorb and process. The value of an image, to me, is in how long it keeps you engaged. With the Rose Reading Room piece, after three or four months of working on it, I’d still catch myself staring at it for ten minutes and zoning out into something I’d been looking at for months. That’s when I know it’s a good piece.

I want my paintings to have replayability, and to take time to absorb and process. The value of an image, to me, is in how long it keeps you engaged. —GB

KC: I get lost in the rendering too. In some of the other works, where it’s less about composition, I’ll find myself really focused on one small area thinking, “Okay, this is going to take hours. There’s no shortcut.” I almost got into a trance. Sometimes I finish a section and realize I don’t even know how I did it. When I’m in that groove, I just trust every move I make [laughs].

GB: That absorption can be an incredibly meditative space. I like losing myself in the act of drawing. It feels like a wave of relief.

LX: I can imagine. You’re both integrating a lot more color in your works since the last time I saw your practice. Kevin, could you take me through this beautiful tableau [gestures to painting]?

Figure 16: Kevin Cobb, LO, 2025, oil, ink, charcoal, graphite, colored pencil, and metallic paint on panel, 60 x 60 inches (152.4 x 152.4 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Kevin Cobb

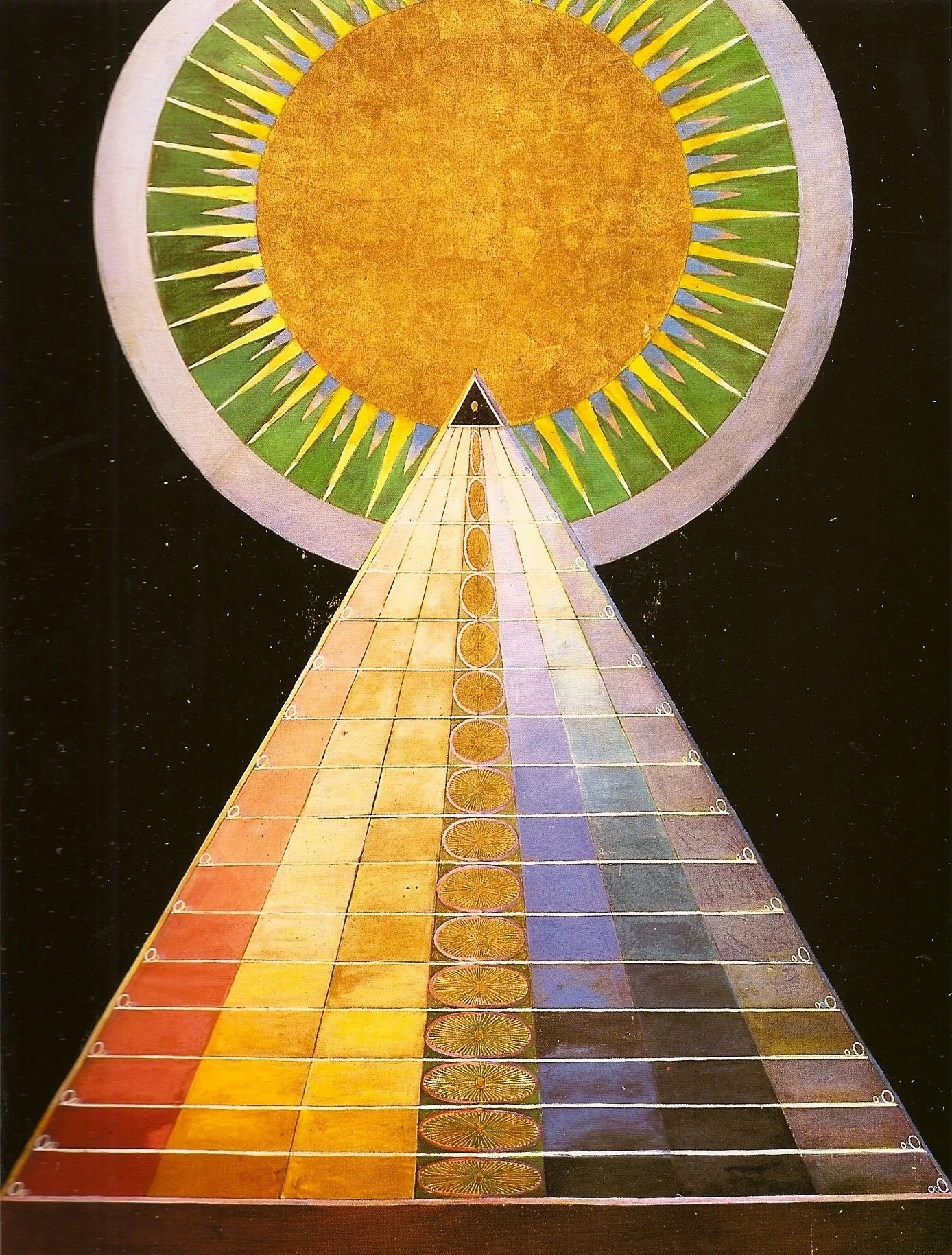

Figure 17: Hilma af Klint, Untitled #1, 1915, oil on gold on canvas, private collection. Courtesy ArtReview

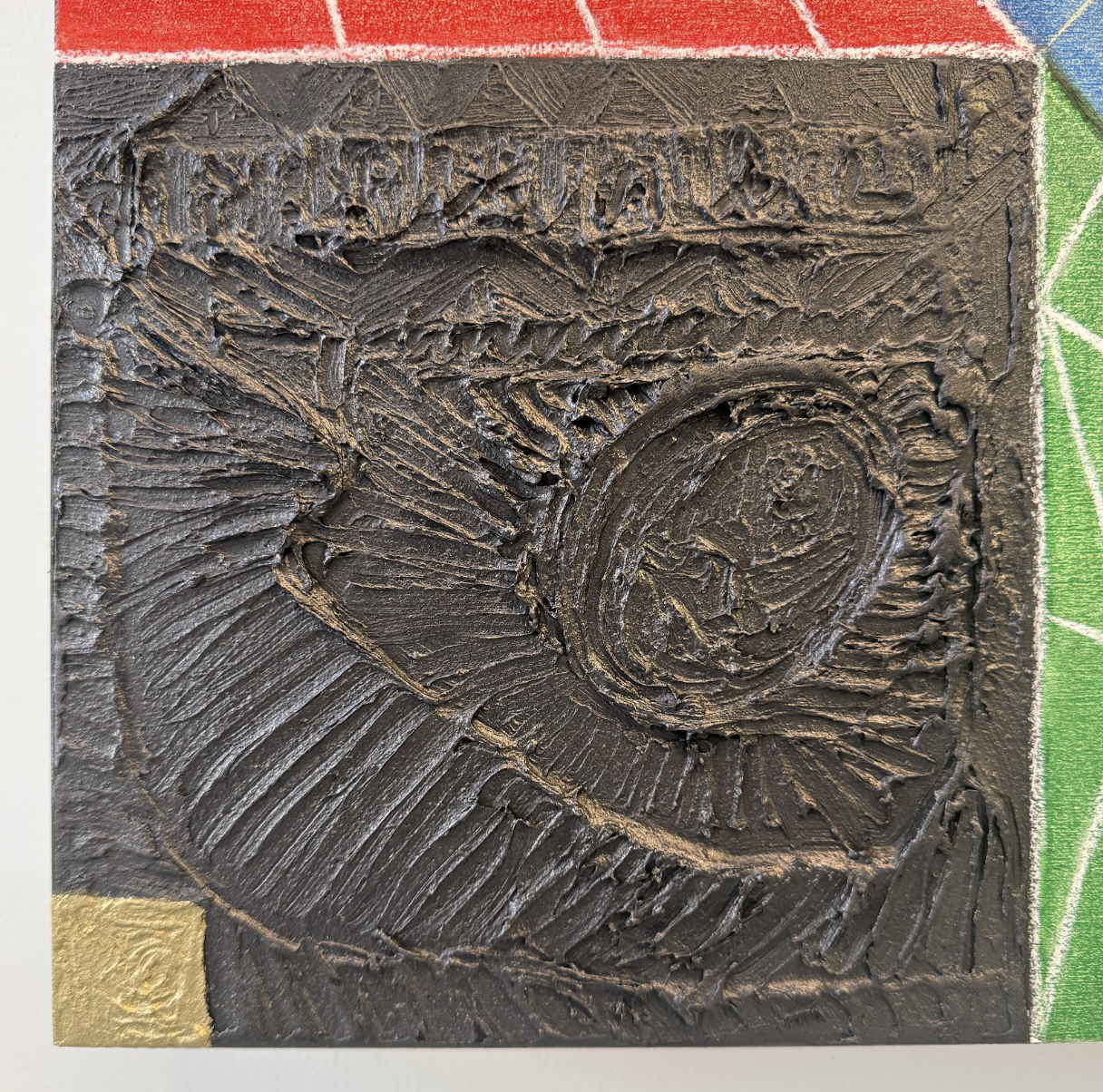

KC: For this one, I built a 3D model with a strange gridded space, and sculpted it out. There were a lot of sketch layers, and I was really interested in deriving figurative poses from simple geometric shapes. The stacked triangles echo the poses I’m making here. For instance, in the last pose where I’m sitting in an L-shape, the silhouette mirrors this large arch. In the middle oval, you’re looking through the eye hole of the blurry L-shaped figure drawn above, and seeing another version of myself drawn with an inverse perspective, where the closest parts of the figure are foreshortened and the furthest parts are lengthened. I’m exploring different ways of depicting space, so this one has more of a flat approach, while my other works feel more spherical and spatial.

LX: It looks kind of Hilma af Klint-y in its color palette and design. It’s like a prismatic blueprint. How did you get the sheen on the right side of all these polychromatic forms?

KC: I literally have af Klint’s books over there, so her work definitely inflects my canvases a little. I really love her work! That sheen was a rainbow originally. I mixed all the colors and blended them vertically in single brushstrokes to create a kind of heat map or chromatic effect that’d suggest energy levels. The composition leans toward a sequential rainbowy color system. You can see the grid I drew in the background that shows through in the white and other areas. Even that, and the whole underlying sketch, was drawn with rainbow pencils, so the lines shift colors as they move along everywhere. Some of the triangular shapes in the background are like an iconographic depiction of the mountains and the grass visible in the little ovular scene.

Figure 18: Kevin Cobb, LO (detail), 2025, oil, ink, charcoal, graphite, colored pencil, and metallic paint on panel, 60 x 60 inches (152.4 x 152.4 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Kevin Cobb

LX: This blueprint component is so cool. Do you draw any inspiration from physics in your practice?

KC: I would say mainly as it relates to optics, light, and philosophy. One physics-related interesting fact I discovered is that the physicist Ernst Mach, who “Mach speed” is named after, was one of the first people to draw a first-person self-portrait in a similar way to what I have been exploring. It seems peculiar that a physicist would be interested in making a work like View from the Left Eye, but it makes sense for him as his physics work stemmed from his unique phenomenological philosophy and method.

Figure 19: Ernst Mach, Self-portrait, 1886, from Beiträge zu Analyse der Empfindungen (The Analysis of Sensations)

As an artist, I particularly love the mythic possibilities of physics. I really love the movie Interstellar because I think Christopher Nolan articulates a mythic link between “gravity” and “love,” and strives to make that link as realistic and plausible as possible. I like using a combination of science and spirituality to see through mundane things, like the mechanical processes of sight in the eye and brain, and invite the possibility of an “Exquisite Corpse” effect on the retina. Simply representing novel ideas and scientific theories in spectacular way, whether in anatomy, psychology, or physics, is also very underrated.

Figure 20: Kevin Cobb, View from the Pyramid, 2024, intaglio etching on Rives BFK, 6 x 6 inches (15.24 x 15.24 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Kevin Cobb

LX: Definitely. That interest is also evident in this dollar bill drawing with you as the focal point [gestures to View from the Pyramid]. I also really respect how curious you both are about the world and how prolifically you make works. It’s been such a treat to watch your practices evolve over time from afar. How would you describe each others’ practice to one another?

As an artist, I particularly love the mythic possibilities of physics. —KC

KC: [Facing Garrett] You use framing and decorative elements to shape your compositions in really intriguing ways. Your use of geometric forms adds a lot of context and dynamism, and your use of printmaking amplifies this. Unlike me, you embrace scale, and engage with the logic of mass production, which creates a fascinating dialogue with the notion of decoration. The ornate buildings you reference gain legitimacy through their ornamentation, and really signal the implied roles of wealth, care, and authority. Your work reveals how decoration functions as a language of power, rather than something dismissed as “women’s work” or mere craft.

Decoration often gets relegated to the ornamental or illustrative, like how people talk about M.C. Escher or Alex Grey, but your work flips that perception, and elucidates that even the most important institutions rely on ornament to project authority. You distort and reframe it, but also expose its capacity to confer power. I’ve always seen decoration as akin to logos or symmetrical designs, or patterns that suggest divinity or universal order. I’ve always felt that the Meander, or Greek key, pattern mainly symbolizes a cyclical view of time. Whether in grand governmental architecture or the ornamented libraries you’ve worked with, you explore the meanings and functions of their designs with real critical depth.

GB: That’s very kind of you, Kevin, I appreciate that. And yes, I’m definitely interested in the vocabulary of power and wealth and institutions. I love looking at Kevin’s work anytime I get the opportunity to because I’m always just struck by the profundity of it and its depth both in terms of the concept and openness to intimacy or sharing. I think that’s something that you and I both share. We both have this interest in the divine or the grand and how that can be channeled through one person and how that can be translated to another in a visual form.

LX: What a beautiful way to rap, fam.

Kevin Cobb

Kevin Cobb (b. 1994, Baltimore, MD) is a multidisciplinary artist who works within painting, drawing, 3D modeling, digital animation, and lens-based media. Working at the intersection of perception, technology, and selfhood, Cobb investigates how contemporary modes of seeing, as defined and molded by screens, simulation, and algorithmic conditioning restructures one’s subjectivity. His swirling, multi-perspectival compositions often bend or fragment the viewer’s vantage point, creating destabilized optical spaces that reflect the tension between physical experience and its digital doubles.

Cobb received his MFA from Columbia University’s School of the Arts in 2023 and his BFA from the Maryland Institute College of Art in 2016. His work has been exhibited at 81 Leonard Gallery, New York, as well as in group exhibitions across the U.S. and Europe. In 2025, he presented his first New York solo exhibition, Ekstasis, which brought together paintings and digital works reflecting on displacement, viewership, and the porous boundary between observer and observed. He is a recipient of the Mozaik Future Art Award (2022) for digital art, and he was nominated for a Fulbright Program award in 2016. Cobb’s practice continues to expand the perceptual and conceptual limits of image-making, merging spiritual inquiry with technological experimentation to propose new ways of optically seeing, and being seen, in a mediated world.

Website: https://www.kevin-cobb.com/

Instagram: @forprophet

Garrett Ball

With an eye towards architecture, infrastructure, and institutions, Garrett Ball (b. 1991 Denver, Colorado) creates intricate paintings and prints that render these rigid structures as malleable, and multifaceted. In a moment when there are multiple and sometimes conflicting viewpoints for every circumstance, Ball creates kaleidoscopic perspectives that force the viewer to acclimate to that disorientation and embrace a view from multiple places. Inspired by the work of speculative realist philosophers, Ball’s images grapple with the notions of superpositionality, object oriented ontology, and hyperobjects. Focusing on the frameworks for our society and culture, Ball suggests that what may seem rigid or inscrutable, is often fabricated and always subject to change. Rendering these structures as variable tools, is a call to action to the audience to not be intimidated by institutions but to reimagine and adapt them to better serve their function.

Born in Colorado (1991) and raised in the Rocky Mountains and on Puerto Rico’s beaches, Ball moved to New York to study theater at SUNY Purchase in 2009. He joined IATSE local USA 829 as a professional scenic artist, Ball has painted on dozens of Broadway and TV/film productions. While painting backdrops and hard scenery professionally, Ball developed his own craft and style. In 2023 he graduated from Columbia University with a masters in fine art, where he was a Neiman Fellow at the LeRoy Neiman Center for Print Studies and received the Betty Lee Stern Prize for Artists. Since graduating he has shown in NYC and Miami at the New Collectors Gallery, Half Gallery, Fredric Snitzer Gallery, the Blanc, Storage Archive, and the University of Richmond Museum, among others. He currently lives and works in New York City.

Website: https://www.garrettscottball.com/

Instagram: @ball_artwork