Mirror Phases: In Conversation with Yuwei Tu

Yuwei Tu makes stunning portraits from “crops of her own skin” and of individuals she knows. Tu speaks with Lara Xenia about her material process, experience of loss, and interest in Lacanian psychoanalysis.

Figure 1: Yuwei Tu, Self-Portrait of a Daughter, 2024, from the Wherever Your Mother’s Shadow Falls series, oil on ACM panel, 12 × 9 inches (30.48 × 22.86 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Yuwei Tu

Lara Xenia: Were you a hyper-observant child?

Yuwei Tu: Yes, I’d say I’ve always been very detail-oriented. Being in my studio probably says that.

LX: How did you end up at Yale?

YT: What a whirlwind. I studied Business at the University of Notre Dame, and worked in corporate fashion in New York for almost five years—I was crunching numbers on Excel all day. After a significant personal event, I realized life is too short and thought, “Let me just take a chance on myself” and pursue my love for art full-time.

LX: Are you technically a self-taught artist?

YT: I've always taken art classes here and there, but otherwise, yes.

LX: That’s incredibly impressive. I was really drawn to the tactility of your work and how exceptionally detailed everything is. What compelled you to deviate from your earlier hyperrealist style towards your current one?

YT: Yes, I think they are still extremely detailed, but not overly. When I arrived at Yale, I was so early in my art journey and was in a specific place of hyperrealism. When I started painting, I was very drawn to Chuck Close. Obviously not for his morals, but the person aside, it impacted me to see his paintings at The Broad when I was really young. That led me down a hyperrealist path. I thought to myself, “Okay, he's a person and I'm a person.” You don't need to be like—art's not like basketball, where if you're not a certain size, you can't do it. If he could do it, what does he have that I don’t? It’s just a matter of practice and determination [laughs].

In my current practice, I'm not interested in laying out a scene or having a character in the background and telling a narrative story. These works feel more like meditations, snapshots or little poems to me. I like that they remain very open in terms of associations and appreciate the quietude of them.

LX: Could you tell me a bit about your material process?

YT: I've been interested in working with seriality, so these lately have been the same size wood panels, 8 by 10 inches. I build up molding paste layer by layer, which lends itself to the flushiness and the organic edge of the surface. Then I sand it down. The thin layers of oil paint gives it that translucency, and allows the different colors to show.

LX: The viewing process feels meditative too because the scale adds an intimacy to them, since the size is almost comparable to a face. Do you consider scale a lot?

YT: I'm drawn to intimate scales for this series. It feels very subtle and quiet, but there’s also something super powerful about it not asserting itself.

LX: I particularly like this work because it looks uneven, almost like a nebula, fleshy or neuron-like.

YT: Exactly. I love existing in that space where it opens it up to: is it skin? Is it bodily? Is it topographical? Is it cosmic? Shifting between micro and macro. Is it the human body, or even some other living beings? I like existing in the space where it evades specificity and it’s always interesting to see what people get out of it. I feel like art is a mirror. It's a reflection of your experiences. These come from images of my own body and crops of my own skin. I was making a body of work before, and then I thought, “What if I cropped this part of my legs and zoomed in to make a more abstracted composition? An evolution of the painting before.” These were already pretty cropped, but not to this degree. I was not trying to set a scene or tell the narrative.

LX: The folds within this closed-off work are unique. What was the logic and story behind the netted one? [Points to work]

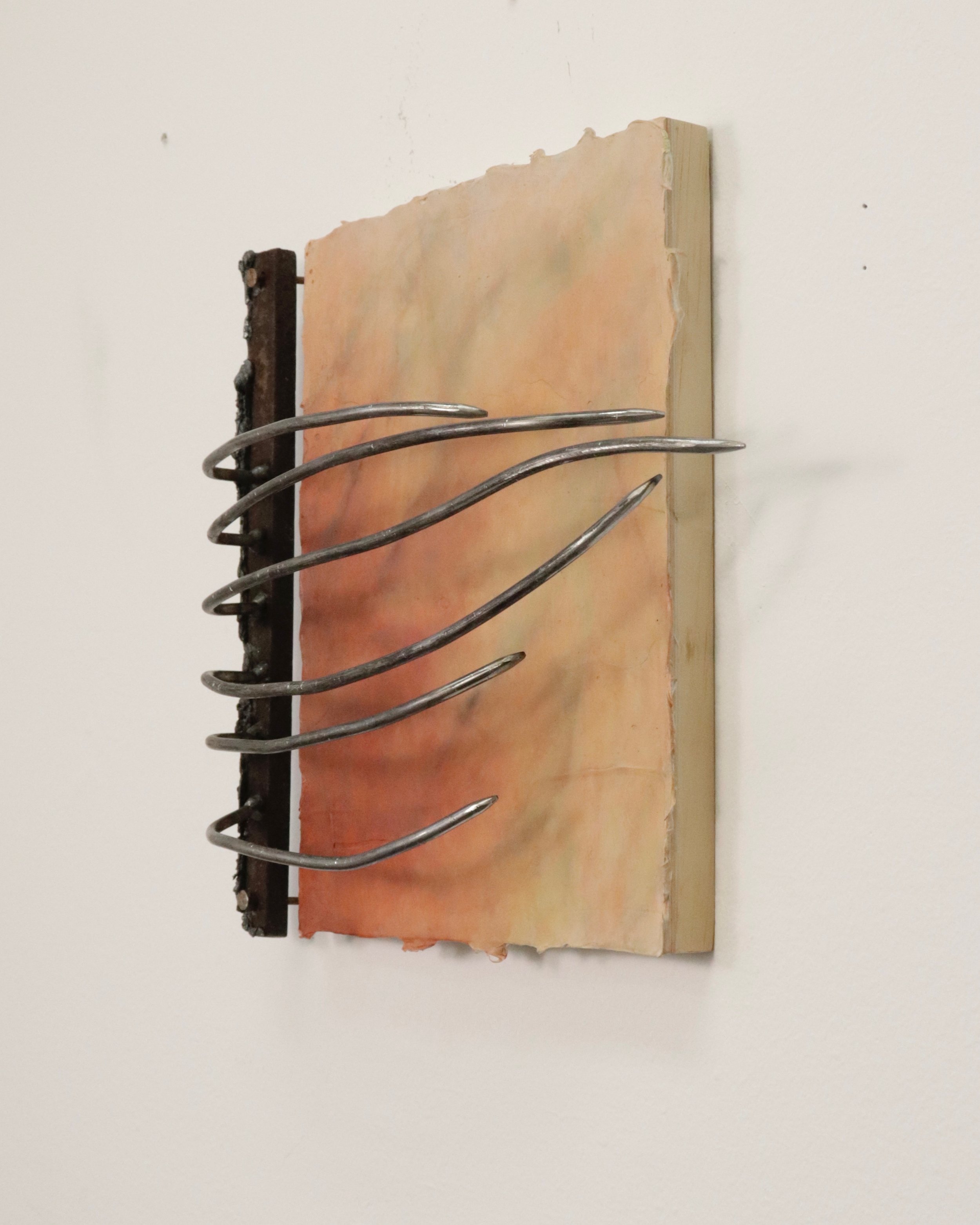

Figure 2: Yuwei Tu, In brace 2025, from the Skin series, oil on panel with steel frame, 10 × 8 inches × 0.75 inches (25.4 × 20.32 × 1.91 cm); overall: approximately 11 × 10 × 2 inches (27.94 × 25.4 × 5.08 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Yuwei Tu

Figure 3: Yuwei Tu, Wear, 2025, from the Skin series, oil on panel with steel frame, 10 x 8 × 0.75 inches (25.4 × 20.32 × 1.91 cm.); overall: approximately 11 × 9 × 1 inches (27.94 × 22.86 × 2.54 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Yuwei Tu

YT: Ah yes, the caging. I recently started going to the metal shop and welding framing devices that become integrated parts of the paintings. My favorite artist is Louise Bourgeois, so I think it was just a matter of time for the metal to manifest itself. I finally got over the mental block of being daunted by the “hot and sweaty” space of the shop itself and showed up. The lady who runs it is so wonderful and has shown me how to use the tools. I’ve been having fun with it. I expected the metals to be rigid, but I appreciate that like oil paint, it’s so malleable and you can form it to do whatever you want; you lay down the brush mark, you weld the joints together, and it comes together in front of you.

Figure 4: Louise Bourgeois, Crouching Spider [Maman], 2003. Courtesy Dia Beacon, Cheim & Read and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Bill Jacobson Studio, New York © The Easton Foundation/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Figure 5: Studio installation view of Yuwei Tu, Skin series, 2025. Photo: courtesy the artist © Yuwei Tu

LX: There’s a certain vulnerability to skin of any kind, whether it be animal skin or other flesh. Would you consider these works formally portraits?

I like existing in the space where it evades specificity and it’s always interesting to see what people get out of it. I feel like art is a mirror. It’s a reflection of your experiences. These come from images of my own body and crops of my own skin.

YT: I consider them all to be self-portraits because it’s quite literally an image of me, or an extension of my consciousness and experiences. For me, they feel disembodied, but embodied at once.

LX: I like their immediacy and that as a viewer, I had absolutely no idea what I was looking at. There's kind of a cognitive dissonance. It’s also important that you’re engaging in this type of self-reflective work as you’re grappling with so many melancholic emotions and life experiences. Could you tell me about this self-portrait on the ground?

Figure 6: Yuwei Tu, Mirror Phases, 2025, liquid latex, oil on yupo, wood glue, and paper pulp from old drawings, approximately 36 × 20 inches (91.44 × 50.8 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Yuwei Tu

YT: This work was a way for me to bring the paintings off the wall and as an interaction with objects and into the world. I used an acrylic medium, and built it on the floor with a palette knife using a liquid mix. Whether it’s through psychoanalysis, psychology, philosophy or Buddhism, I'm always interested in different understandings of how we get to know the self and each other. This work came about from reading Jacques Lacan’s “Mirror Stage” in class. It got me thinking about the self, and these broader metaphors of interiority, breaking down the nuance and complexity of how everything's a mirror of yourself. I love how there's no straightforward answer to dualities. I decided to make a series of daily self-portraits while observing myself in the mirror, seeing the formation and making these different skins.

LX: Why did you decide to make this a serial image?

YT: I guess in thinking about Lacan’s theory, there’s this theme of seriality at work. I was interested in how our ego is formed through identifying with our self-image in the mirror. It also ties back to the concept of meditations, since these were a series of daily self-portraits that I made by looking literally in the mirror. I made it for 15 days, so 15 sheets, and was just sheerly thinking about the observation of myself and how, even though I'm drawing the same subject, I appear to myself so differently each day. I think to really see yourself and know yourself, still feels so impossible. The person you know most intimately, from beginning to end, in and out, I'm still trying to bring out.

LX: It's like melted Asiago cheese [laughter].

YT: I like the air system and the shift between something really tender and beautiful, with something that’s a little bit repulsive and gnarly.

LX: What have you learned about yourself as you were making this specific series?

YT: It’s made me question how I like to approach things in life, and how that fits in my approach to my practice. This room for nuance and ambiguity is how I see a lot of interactions or relationships with different people in life.

LX: Can you tell me about your series Wherever Your Mother’s Shadow Falls?

Figure 7: Yuwei Tu, Wherever Your Mother’s Shadow Falls, from the Wherever Your Mother’s Shadow Falls series, 2024, oil on ACM panel, 14 × 11 inches (35.56 × 27.94 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Yuwei Tu

YT: Yes, that came from an Ocean Vuong poem. I'm obsessed with him; he’s my favorite writer, poet, and thinker. I made that painting partially inspired by his poetry and also in relation to my personal life, because my mom passed away in 2018 and that work is dedicated to her. That’s also why I think it influenced the whole shift to art in general. Life is too short; you can't take a single day for granted. My mother was in China, and a lot of my family is still there. It took me some time to process things. I was still working in fashion, but I think I took time to process, grieve, and record it…I had no semblance of what being an artist looks like. Looking back now, it was really terrifying, but it all worked out. For that show, I was considering grief and longing a lot, through my hands specifically, through the sense of touching and reaching out.

LX: Has your identity ever come into play in terms of how you view your works or to some extent, is it informed by it?

YT: I think you can't deny that it's inescapable because the work comes through me, and it's a reflection of me, and my background, my life, my race, my gender. It’s all inevitable, even if I'm not so intentionally or on the nose standing here saying, “I'm making work about being an Asian American woman.” Those elements of your gender and your race come through your work. In the context of viewing it, I think about what it means for an Asian woman to be making this type of work and how it would mean something very different for a white man to be making this. I definitely think about that and am always trying to be mindful, especially now in the art world. We see so much pandering of identity politics.

LX: I’ve recently been thinking a lot about Ann Anlin Cheng’s work and personally love her books Second Skin and Ornamentalism. They both fundamentally changed my perspective on the language used for describing how we even talk about skin and early architectural theory. Your work made me wonder if you ever subtly are confronting those ideas in your practice.

YT: Yes, I reference her writing often. I think my metalwork brings in that conversation with the decorative and the ornament. From Ornamentalism, we can think about how especially for an Asian woman, the way you present yourself and your skin and the surroundings that you appear in the decorative ornament all tie to your identity and how you're perceived. We talked about this in crit; my wonderful faculty member Anoka Fauci mentioned it. I’ve had this conversation with her a few times about this hierarchy, especially in Western art, of the decorative and ornament being art, philosophy, architecture, with it being seen as superfluous and excess and not fundamental to the structure and integrity of something and gendered as feminine. We discuss what that means. I'm not really trying to be saying, “This is good, this is bad,” but rather more so about probing “racing questions” and “Why do we think this way? Why do we see things this way?” What are these hierarchical structures of power and value systems that we've been brought to believe and live under?” These are the questions I prefer to raise.

Let me read you this poem by Vuong quickly. It’s called, “Someday I Love” by Ocean Vuong:

Ocean, don't be afraid. The end of the road is so far ahead it is already behind us. Don't worry. Your father is only your father until one of you forgets. Like how the spine won't remember its wings no matter how many times her knees kissed the pavement. Ocean, are you listening? The most beautiful part of your body is wherever your mother's shadow falls. Here's the house with childhood whittled down to a single red trip wire. Don't worry. Just call it horizon & you'll never reach it.

LX: Wow.

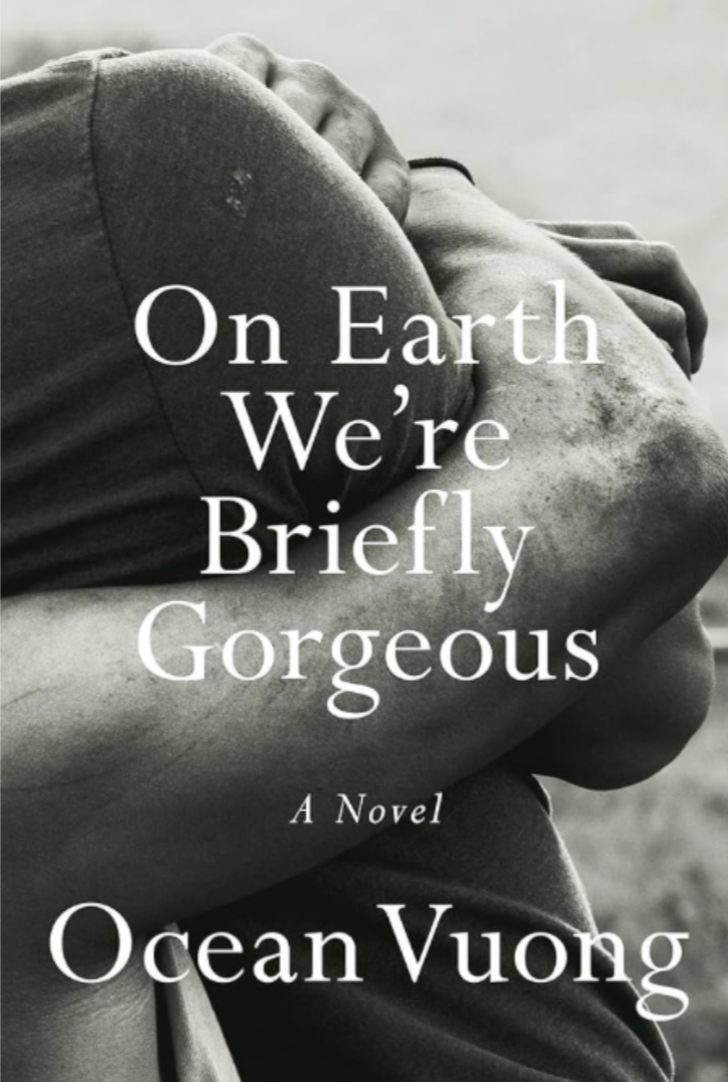

YT: That's a snippet of the poem, but the way he uses words is profound…he wrote a novel called On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, which is his most well-known piece and the cover has a whole bodily component. I just found out that this cover photo was taken by one of my professors here, Sam Contis, whom I absolutely adore. I was taking a photography class last semester, and it turns out the image is hers. It felt especially serendipitous because I had already created a body of work inspired by Vuong for my application—only to later learn that the class before mine had read his poetry during the school-wide readings. There have been so many moments like this where everything just seems to align.

Figure 9: Ocean Vuong, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous, 2024, featuring cover photograph by Sam Contis © Sam Contis

LX: Did you read a lot to cope at the time? Do you feel like you’re mentally channeling your mum in your practice and beyond?

YT: I'm struck by how writers and poets use their words. I hope the paintings serve as visual poems.

LX: That’s amazing that you helped someone see themself in a different light. Is this your friend?

YT: Yes, that is one of my best friends, Rilke Noel. I wanted to paint her in a way that was very stripped down and vulnerable, but not sexualized. I see her as my best friend, almost a sister.

Figure 11: Yuwei Tu, Sunday Morning with R, 2022, oil on ACM panel, 24 × 20 inches (60.96 × 50.8 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Yuwei Tu

LX: She appears very dignified here. How long do the hyperrealist works take?

YT: Months. I start off with very blocky layers, then apply them very thinly each time. I always say I sketch with the camera. It's important for me to find the composition through that.

I hope the paintings serve as visual poems.

LX: High Maintenance looks like a great show.

YT: Yeah that was during COVID; I didn't realize that at the time, but one of my classmates here, Amy Chasse downstairs, was actually in that group show with me before we both got into Yale. We had no clue. She’s great; we can have fun and not take ourselves so seriously.

LX: Yes, her carnival works are awesome. What’s this lily tableau about?

Figure 13: Yuwei Tu, Week-Old Lilies, 2024, from the Wherever Your Mother’s Shadow Falls series, oil on ACM panel, 20 × 16 inches (60.96 × 50.8 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Yuwei Tu

YT: I was pontificating about the passage of time, on the verge of life and death. My mom's name sounds really close to Lily in Chinese. I always think of her and how she loved flowers and associated lilies with her and mourning.

LX: And Already Behind Us?

YT: Yes. That watch was for her. The show is for her, and this was part of that series. There’s something about the pose and the back turn and interlocked hands. When I was in LA, I would wear it basically every day. It was funny because I think my dad had actually gifted her that watch and it stopped working the day after she passed. I kind of love that idea that time stopped. I could have taken it to a watch repair place and gotten it fixed and running, but I like the idea that time just stopped with her. I think it’s so poetic.

LX: That’s beautiful. So that’s you posing?

Figure 14: Yuwei Tu, Already Behind Us, from the Wherever Your Mother’s Shadow Falls series, 2024, oil on ACM panel, 20 × 16 inches (60.96 × 50.8 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Yuwei Tu

YT: Yes, I was thinking of the idea of turning away, and also the significance of denim jeans and moving to America. I was born and raised in China, then I moved to L.A. when I was 8, and my parents got divorced when I was really young.

LX: I see. To conclude, I also love this Joker painting. What's the story behind it, and why the Joker?

Figure 15: Yuwei Tu, Joker, 2024, from the Wherever Your Mother’s Shadow Falls series, oil on ACM panel, 14 × 11 inches (35.56 × 27.94 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Yuwei Tu

YT: My mom passed on April Fool's Day. It was such shocking news that I felt delirious for days. I remember receiving that news that morning and thinking, “Is the universe playing a prank on me right now?” We all have moments like that, even when they are so silly, like spilling coffee down your new shirt or something, or where you're thinking, “Are you kidding me?” I remember that day, I couldn’t help but say, “Wow, I can't believe it's April Fool's Day. It feels like the universe is just playing a prank on me.” Part of the process through grief is denial and disbelief. I wondered if someone was going to pinch me or if I was going to snap out of it.

Yuwei Tu

Using a layered process, Yuwei Tu (b. 1995, Sichuan, China) articulates the nuance and complexity of interiority through painting. Her work is informed by personal experiences and investigations in the construction of identities and relationships to create a visual language of the psyche. She is currently pursuing an MFA in Painting/Printmaking at Yale School of Art, class of 2026.