Resisting Death: In Conversation with Inkpa Mani

A prolific painter and sculptor, Inkpa Mani creates art that reflects Indigenous resilience, spirituality, and erasure. Mani speaks candidly with Lara Xenia about his passion for linguistics, his connection to stone, and the evolution of his practice.

Figure 1: Inkpa Mani, The Spirit of Migration Has a Horse, 2024, oil on birch panels, 96 × 96 inches (243.84 × 243.84 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Inkpa Mani

Lara Xenia: What initially drew you to art?

Inkpa Mani: Growing up between Chihuahua, Mexico, and Minnesota, my earliest artistic memories involve finding Casas Grandes pottery shards during mountain walks. My grandfather, a rural farmer, taught us to respect these remnants, reminding us, “It is no longer us, but it is part of us.” Encountering Indigenous aesthetics, with its geometric abstraction and handmade beauty, deeply impacted me.

Figure 2: Anonymous artist, Jar with Four Faces, ceramic Casas Grandes vase, mid-13th–mid-15th century, Mexico, Mesoamerica, Chihuahua, Mexico, height 8.69 inches (22.1 cm), The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, (1979.206.1171)

Later, my stepfather, a Dakota Sioux man from the Lake Traverse Reservation, significantly influenced my worldview by introducing me to Dakota traditions when I was seven. I was profoundly shaped by hearing oral histories, witnessing ceremonies, and participating in dances like the matachines, which blends traditions from Indigenous communities in northern Mexico, the American Southwest, and Northern Plains Dakota Sioux culture. Experiencing how our traditions were simultaneously revered in churches yet mocked socially pushed me toward making art. My work became a way to honor these contradictions, stories, and resilience in the face of cultural erasure.

LX: Could you elaborate on the meaning and significance of your Dakota name, Tachakpi Tokahe Inkpa Mani?

IM: My name translates roughly to “My spirit walks at the leading edge,” symbolizing mindful leadership and thoughtful action. The Dakota language holds nuances best understood through storytelling. I was given my Indian name by the Spotted Eagle Clan when I was 16. The elders explained it metaphorically with a visual as the lead goose in migration, breaking wind resistance for others, or as sunlight piercing through clouds—an initial ray of clarity. Using Inkpa Mani publicly honors my spiritual identity, family’s cultural beliefs, and guiding philosophy. While some critics mistakenly suggest it is performative, embracing this name genuinely reflects my identity and my upbringing within my community.

Living and working around the reservation and in some Native American spaces, I’ve become acutely aware of a broader absence of recognition for Indigenous peoples from Latin America and the Caribbean. This lack of cross-cultural awareness often results in the erasure or marginalization of Indigenous narratives that originate south of the U.S. border, reinforcing colonial boundaries of what is considered "authentically Indigenous." As someone whose family ancestry comes from Chihuahua, Jalisco, Mexico City, and the Yucatan, I have experienced my name weaponized in derogatory ways to question my legitimacy—reflecting how entrenched these boundaries are. Embracing and using my Dakota spirit name, Inkpa Mani, is not only an act of spiritual alignment and cultural reclamation, but also a deliberate resistance against those imposed colonial definitions of Indigeneity.

LX: You've openly addressed challenging questions of identity and appropriation, especially following your Minneapolis Water Works public commission. What was that experience like?

IM: At 23, I was awarded a $450,000 public art commission to honor Dakota history at Owámniyomni (St. Anthony Falls). My deep cultural ties through my adoptive Dakota Sioux family significantly informed my proposal. However, misunderstandings about my tribal enrollment status led to accusations of cultural appropriation, triggering intense scrutiny and a personal reckoning. This experience was part of why I chose Yale. I needed space to critically navigate my identity, authenticity, and responsibility as an Indigenous artist. The introspection from that period continues to shape my practice, making me more deliberate and culturally accountable.

LX: Your previous portrait series seeks to restore autonomy to Indigenous representation. What inspired these portraits?

Figure 3: Inkpa Mani, Portrait of Audrey German (“Rattling Chains Woman”), 2023–2024, oil over acrylic on canvas, 48 × 36 inches (121.92 × 91.44 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Inkpa Mani

My work became a way to honor these contradictions, stories, and resilience in the face of cultural erasure.

IM: Historically, images of Indigenous peoples were manipulated to reinforce false notions of a "dying race." My portraits intentionally counteract this by directly collaborating with my community. Elders and peers recommend individuals who exemplify integrity and whose stories deserve to be honored and remembered.

For example, Audrey German (“Rattling Chains Woman”) was repeatedly suggested. Her name honors ancestors executed during the 1862 Minnesota mass hanging, where Dakota warriors, still chained, walked proudly toward their deaths. Those chains became symbolic of dignity and resilience rather than oppression. Audrey’s portrait incorporates symbolic red markings rising from her throat, representing sacred speech, spiritual strength, and integrity, ensuring future generations understand her legacy.

Figure 4: Inkpa Mani, Portrait of Audrey German (“Rattling Chains Woman”) [detail], 2023–2024, oil over acrylic on canvas, 48 × 36 inches (121.92 × 91.44 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Inkpa Mani

LX: Stone plays a profound role in your material practice. Could you tell me more about your relationship with it?

IM: Dakota teachings view stones as our “grandfathers,” as the minerals within them mirror our own bodily composition. My adoptive grandmother, Pat Gill, taught me about this profound interconnectedness. Granite’s geological cycle—transforming from magma into sand, sandstone, limestone, marble, then back into granite—symbolizes endless renewal and permanence. By using crushed stone, marble dust, and natural pigments, my practice embodies these spiritual and geological cycles, directly engaging themes of permanence, resilience, and memory against the threat of erasure.

LX: The theme of "resisting death" recurs often in your work. How has this concept personally and artistically motivated you?

IM: "Resisting death" isn’t just metaphorical; it's deeply personal. My mother and both of my grandmothers passed away young, in their forties and fifties. Many men in my life were absent or lost prematurely. The guarantee of longevity has not been afforded to my family line. Knowing life’s brevity firsthand, my art became a way of resisting this mortality, actively preserving stories, people, and cultural practices that would otherwise risk disappearance.

Figure 5: Inkpa Mani, Pink Shells in the Sky; My Mother Dies, 2024, oil and acrylic on wood panel, 46 × 32 inches (116.84 × 81.28 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Inkpa Mani

Works like Pink Shells in the Sky; My Mother Dies directly engage these themes. Imagining shells thrown toward a pink sunset became a symbolic representation of my mother’s spirit, an active resistance to the erasure of her presence. Similarly, Sand in My Eyes, Sand in My Heart incorporates crushed stone and marble dust, symbolically addressing grief, loss, and the desire for continuity through the interplay of abstraction and materiality.

Figure 6: Inkpa Mani, Chihuahua MX, Landscape, 2025, oil, acrylic, stone dust, iridescent pigment on wood panel, 44 × 32 inches (111.76 × 81.28 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Inkpa Mani

IM: This painting holds deep emotional resonance. It references my ancestral lands in the Copper Canyons within the Sierra Madre mountains, with geometric abstraction symbolizing those rugged peaks and valleys. My ancestors watched countless sunrises illuminate those mountains, turning them vivid, cool colors. The materials—shells traded from distant coasts, turquoise, and shell necklaces—reflect ancient trade networks and signify cultural status and connection. The three squares in my compositions often symbolize past, present, and future, echoing traditional Sioux beadwork that similarly uses geometric forms to represent concepts like duality or the four directions.

LX: Fascinating. You’ve also expressed interest in granite. What materials did you use in Sand in My Eyes, Sand in My Heart? Are you drawn explicitly to using rock materials in your practice, and if so, do you grind the stone yourself?

Figure 7: Inkpa Mani, Sand in My Eyes, Sand in My Heart; All Stones Turn To Dust, 2025, crushed stone, marble dust, quartz sand, acrylic medium, and powdered pigments on canvas, 36 × 36 inches (91.44 × 91.44 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Inkpa Mani

IM: Absolutely. Sand in My Eyes explores my profound relationship with stone, rooted in Dakota teachings from my adoptive grandmother, Pat Gill. She described stones as “grandfathers,” reminding me, “Every mineral in stone also exists within you.” Granite shares fundamental elements like silica and iron with our bodies, reinforcing our interconnectedness. This understanding of geological and spiritual kinship deeply informs my practice. Stone represents endurance and renewal—magma eventually transforms into granite, which erodes to sand, sandstone, limestone, and marble, before ultimately returning to granite, symbolizing endless cycles of resistance to death and continuity, even in this Anthropocene epoch when human existence itself becomes layered into geological history.

LX: I’ve never thought about life cycles in that way. It’s beautiful how Indigenous communities often share an intimate, multifaceted relationship with the earth and its materials, reflected so powerfully in your work. You've also mentioned memorialization—it’s a universal impulse to preserve memory. Your work increasingly explores abstraction, even though you've maintained a reverence for representational forms. What draws you toward abstraction?

IM: While I hold a deep reverence for representational portraiture and its explicit narrative power, abstraction offers a language uniquely capable of expressing the intangible—complex emotional realities, cultural memories, and spiritual dimensions of my experiences. Abstraction allows viewers multiple entry points, moving beyond literal representation to evoke deeper, universal feelings of grief, resilience, loss, and hope. It reflects the complexity of my mixed heritage—Tarahumara, Mexica, Polish, Spanish—and allows me to engage in nuanced internal dialogues around identity and authenticity without restricting the conversation to a single, fixed image.

She described stones as ‘grandfathers,’ reminding me, ‘Every mineral in stone also exists within you.’

LX: Could you tell me about your community-informed sculpture commission on the Lake Traverse Reservation?

Figure 8: Inkpa Mani, Dakuska: Sacred Movement, 2024, 60,000 lbs of Dolomite limestone, 56 × 3 × 10 ft (1,706.88 × 91.44 × 304.8 cm), Sisseton, South Dakota. Photo: courtesy the artist © Inkpa Mani

IM: My original proposal wasn’t chosen due to complexity, but we pursued community-led dialogue instead. Elders emphasized the importance of honoring women’s vital roles, both historically and today. This led to the sculpture Dakuska: Sacred Movement, a tribute to Dakota women. The central grandmother figure holds both traditional objects and contemporary symbols, like an Apple Watch. Seven pillars behind her embody the Dakota principle of considering seven generations in every decision, marked with modern petroglyphs and handprints affirming continuous presence. The sculpture’s design intentionally facilitates community interaction and offerings, reinforcing shared histories and collective futures.

Figure 9: Inkpa Mani, Black Sunflower, 2024, oil over acrylic on canvas, 48 × 36 inches (121.92 × 91.44 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Inkpa Mani

LX: That’s so beautiful. As we discussed in your studio, your recent self-portrait series confronts deeply personal themes. What prompted that exploration?

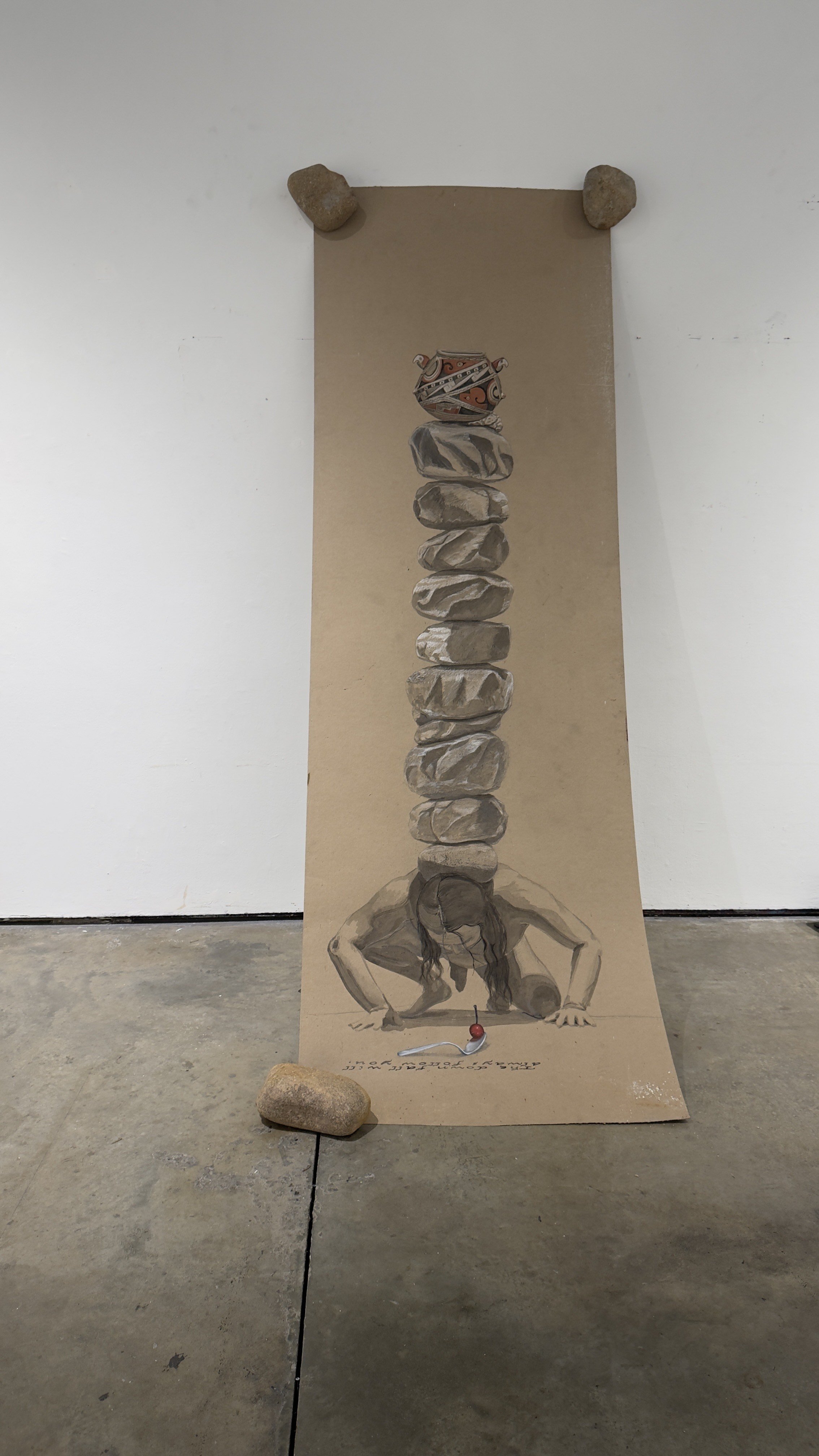

Figure 10: Inkpa Mani, Taku Eye Kte?: What Will I Tell Her?, 2025, acrylic and oil on ram board and basalt stone, 10 × 3.5 feet (304.8 × 106.68 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Inkpa Mani

Figure 11: Inkpa Mani, The Down Fall Will Always Follow You, 2025, acrylic and oil on ram board and basalt stone, 10 × 3.5 feet (304.8 × 106.68 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Inkpa Mani

Figure 12: Inkpa Mani, Installation view of Anthropophagy: Exodus 20:12, 2025, acrylic and oil on ram board and basalt stone, 10 × 3.5 feet (304.8 × 106.68 cm). Photo: courtesy the artist © Inkpa Mani

IM: These self-portraits grapple explicitly with the complexities of my mixed heritage and tensions surrounding authenticity, representation, and cultural consumption. Intentionally uncomfortable, they incorporate unsettling materials—obsidian knives, pig hearts, rat poison—to represent internal struggle, ancestral trauma, and the anxiety around identity authenticity. Yale provided me with a protected space for this vulnerable introspection, enabling honesty without immediate external pressures. While unlikely to become traditional museum pieces, these works remain crucial for navigating and processing unresolved emotional and cultural tensions, making space for future artistic clarity.

Inkpa Mani

Inkpa Mani (he/him) honors the people, places, and spirits that shape his life in his painting practice. Working with acrylic, oil, and stone, he creates textured, abstract surfaces grounded in Indigenous aesthetics. Drawing from the landscapes and cultural traditions of the Great Plains and Northern Mexico, his work engages the spiritual and material legacies of his ancestors. Through surface, color, and geometry, Mani expands the possibilities of Indigenous art—resisting homogenous flattening, hegemony, and placing his voice within a long and evolving history of abstraction. He is an Indigenous Mexican-American painter, stone sculptor, and educator. Raised between Chihuahua, Mexico, and the Lake Traverse Reservation in Minnesota, he is of Tarahumara, Conchos, and Masea Mexica descent. His work draws from Indigenous abstraction and figuration to explore resistance to death, rematriation, and cultural continuity. Indigenous aesthetics shape his paintings and stone sculptures through material exploration, symbolic form, and cultural memory, carrying forward stories of survival, spirituality, and ancestral belonging.

Mani holds a BFA from the University of South Dakota, where he was an Oscar Howe Curatorial Fellow. His work has been exhibited at the Plains Art Museum, Akta Lakota Museum, Two Rivers Gallery, and All My Relations Gallery, and he has been commissioned for public art projects by the City of Minneapolis, Yale Divinity School, Williams College, and the State of North Dakota. Mani has also worked as a visual art educator in secondary and post-secondary institutions, supporting Native students and communities through culturally grounded arts education.